An Almost-Blessing and an Almost-Curse for an Almost-Chosen Nation

An extensive literature has emerged in the past decade documenting the Biblical and even rabbinic foundations of the American Revolution, starting with Eric Nelson’s The Hebrew Republic (2011), and including Eran Shalev’s American Zion: The Old Testament as a Political Text from the Revolution to the Civil War (2013), Daniel Dreisbach’s Reading the Bible with the Founding Fathers (2017), and Yeshiva University Straus Center edited volume Proclaim Liberty Throughout the Land (2019). At the center of this discourse is Lincoln’s celebrated qualification of Americans as an “almost-chosen people,” a phrase the historian Paul Johnson identified with America’s calling as “the world’s most powerful and enthusiastic champion of democracy.”

Johnson’s discourse, the text of First Things’ 2006 Erasmus Lecture, was published at a moment when America’s political leaders believed that the Biblical injunction to “proclaim liberty throughout the land” required we “export democracy throughout the world.” In that vein, we dissipated our moral and financial resources on failed foreign adventures and neglected our own circumstances at home, confusing asset bubbles with national wealth. The end of the Cold War left America in a stronger relative position than any power since Rome, yet now we are at severe risk of becoming second rate.

In our impulse for self-congratulation, we tend to think of this Lincolnian National Election as a cosmic testimonial of some kind. In that respect America is in no way unique. Every one of the European kingdoms styled itself “chosen” at some point in its history, starting with dei gesta per Francos during the First Crusade. As I reported in my book How Civilizations Die (2011), each one of the belligerent powers of World War I asserted its own superiority using the language of national election. This sensibility resonated into World War II: Hitler’s “Master Race” was a satanic parody of the Election of Israel. To the extent that we appropriate Lincoln’s language merely to reinforce our self-esteem, we ape the illusions of the fallen powers of the Old World.

Nonetheless, I believe that a deep analogy exists between the Election of ancient Israel and the “almost-Election” of America. But it is not a reassuring or happy one, and it exposes our flaws more than it does our virtues. Election is a mission whose abandonment or betrayal brings punishment. The notion that our national character could be reproduced elsewhere in cookie-cutter fashion has always been a delusional exercise in national narcissism.

National Sin and Redemption

What makes us unique is our capacity to persuade immigrants to abandon their ancient culture and instead adopt America’s revolutionary ethos, with its Christianized adaptation of Israel’s redemptive history. We are not one culture among many, but a break with the Old World’s concept of a Kulturnation. Immigrants to America emulate Rip van Winkle: They awake from the once-upon-a-time of their ageless culture, into the bright light of the American future.

With almost-chosenness comes an almost-blessing and an almost-curse. Ulysses S. Grant wrote in his Memoirs about the 1846 Mexican War,

[Texas] had but a very sparse population, until settled by Americans who had received authority from Mexico to colonize. These colonists paid very little attention to the supreme government, and introduced slavery into the state almost from the start, though the constitution of Mexico did not, nor does it now, sanction that institution … The occupation, separation, and annexation [of Texas] were, from the inception of the movement to its final consummation, a conspiracy to acquire territory out of which slave states might be formed for the American Union…The Southern rebellion was largely the outgrowth of the Mexican War. Nations, like individuals, are punished for their transgressions. We got our punishment in the most sanguinary and expensive war of modern times.

Grant evinced a moral grandeur sadly missing in the self-congratulatory discourse of recent American politics. America sinned and was punished; one might extend Grant’s indictment of the Mexican War to the acceptance of slavery at the Founding.

Nations regularly use the language of national election to assert their superiority; only America self-consciously embraced the Hebrew concept of sin and redemption to understand its position in the Civil War.

That is the message of Lincoln’s Second Inaugural, but it was already embedded in the popular mind. Julia Ward Howe sang in “The Battle Hymn of the Republic” of “grapes of wrath,” invoking the fearful imprecation of Isaiah 63, when God comes from Edom with his garments stained red, saying

I trod a vintage alone;

Of the peoples no man was with Me.

I trod them down in My anger,

Trampled them in My rage;

Their life-blood bespattered My garments

And all My clothing was stained.

For I had planned a day of vengeance,

And My year of redemption arrived.

“He is sifting out the hearts of men before His judgment seat,” Howe wrote later in the poem. But her reference to Isaiah makes clear that she understood the Civil War just as did Grant: “Nations, like individuals, are punished for their transgressions.”

Richard Brookhiser believes that a religious conversion separates the Lincoln of the Gettysburg Address from the Lincoln of the Second Inaugural, with its explicit reference to a Providence that directs human affairs in a way that men may not find congenial: “Woe unto the world because of offenses; for it must needs be that offenses come, but woe to that man by whom the offense cometh.”

In a famous letter to Thurlow Weed, Lincoln averred that the address was not likely to be popular:

Men are not flattered by being shown that there has been a difference of purpose between the Almighty and them. To deny it, however, in this case, is to deny that there is a God governing the world. It is a truth which I thought needed to be told…

Prophetic words were these.

By the turn of the 20th century, the apocalyptic Protestantism of the Civil War had moldered into Social Gospel and universal salvation. As Louis Menand observes in his 2002 book The Metaphysical Club, the horrific experience of the Boston elite in the Civil War convinced the generation of William James and Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. that no truth was worth the awful sacrifices they witnessed as young soldiers. The horrors of the Civil War desanguinated their idealism and purged them of their Puritan convictions and left in its stead the banal pragmatism that has reigned since in American elite culture. The South could not accept its defeat after horrific sacrifice. North and South agreed to bury Lincoln’s legacy. The outcome of this agreement was the alliance of the Social Gospel movement with the Progressivism of Woodrow Wilson, an apologist for the Confederacy. This became the mainline Protestant consensus, and it reigned in American culture until the 1960s.

Reshaping the Globe

With the Social Gospel movement, the Protestant Mainline elected instead to fix the world in such a way as to escape the judgment of Heaven which Lincoln had called “true and righteous altogether.” Wilson, an early convert to the Social Gospel, extended this religion of earthly success to foreign policy.

In my view, conservatives put too much emphasis on the malign influence of a handful of left-wing émigré ideologues—the cultural Marxists of the Frankfurt School. The sudden collapse of the liberal Protestant mainstream in the face of the counterculture of the 1960s occurred not because we were reading Horkheimer or Marcuse, but because the Mainline’s smug self-assurance crashed against the moral messiness of the Vietnam War. Liberal internationalism, the United Nations (for whose UNICEF branch we gathered pennies at Halloween), and decolonization were supposed to make the world a better place. That was the world of the Dulles Brothers and Henry Cabot Lodge. At the end of the day, all they left us was the horrifying illogic of the body count. That is what my generation rejected in the 1960s. We ran into the cultural Marxists later, after we were radicalized by events.

To put it bluntly: We Americans didn’t like Lincoln, except in those few war years of inspiration when our blood surged and our hearts pounded. We still don’t like him. We have concocted a sort of Disney character, Kindly Old Abe, and buried the warrior who proposed to requite every drop of blood drawn from the lash with one drawn from the sword.

In his First Inaugural, Lincoln repeated that he had “no purpose, directly or indirectly, to interfere with the institution of slavery in the States where it exists, adding, “I believe I have no lawful right to do so, and I have no inclination to do so.” He offered to support a Constitutional amendment stating that “the Federal Government shall never interfere with the domestic institutions of the States, including that of persons held to service.”

But Lincoln refused to assure the South that slavery would be allowed to expand. Cotton exhausted the soil and the slave economy required ever more territory. Restricted to its existing domain, slavery would wither away gradually. Lincoln could have averted secession by accepting Jefferson Davis’ proposal to seize Cuba for new slave territory, and exchange restrictions on the domestic expansion of slavery in return for “the Southern dream of a Caribbean Empire,” in historian Robert May’s words. Lincoln could have preserved 700,000 American lives at the price of propagating slavery to the Caribbean, Mexico, and points further south.

The Last Drop of Blood

Lincoln’s stance evinced the moral grandeur of a leader who believes that God punishes the nations for their transgressions.

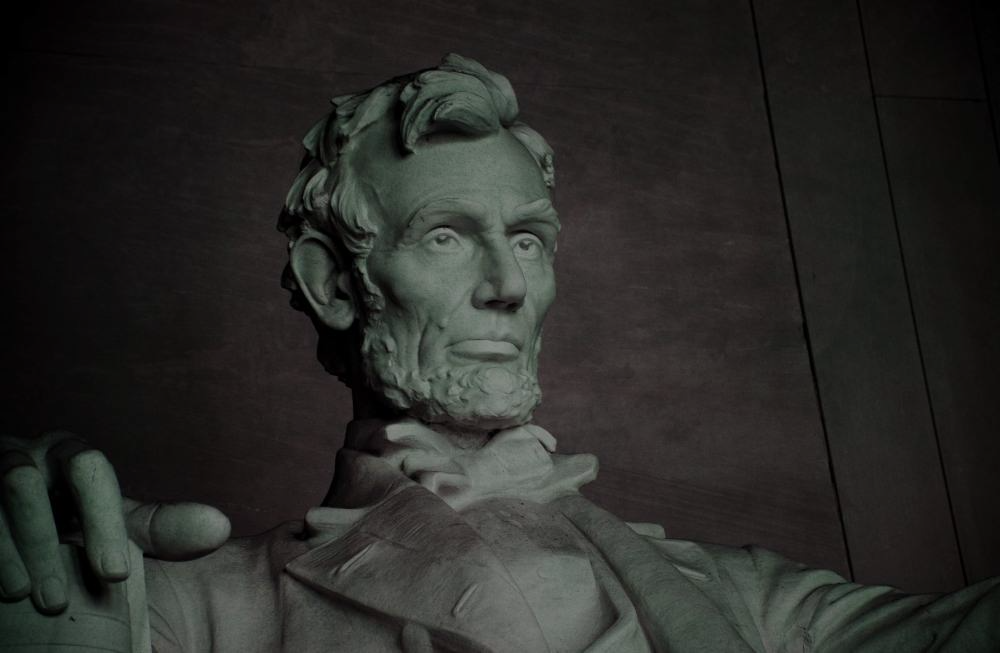

Americans decided that they would rather not have a God who demanded sacrifice from them on this scale—10 percent of military-age Northern men and 30 percent of military-age Southern men. They did not want to be a Chosen People held accountable for their transgressions. They wanted instead a reticent God who withheld his wrath while they set out to make the world amenable to their own purposes. As for Lincoln: We have locked him up in a bathetic parody of a Greek Temple, and seated him on a marble throne like the statue of Zeus at Olympus.

Most wars are avoidable. But some wars need to be fought, in order to give everyone who wants to fight to the death the opportunity to do so. These are existential wars in which the combatants believe that their future is in the balance, and that it is better to die on one’s feet than live on one’s knees. Nations do not actually fight to the death, but they sometimes fight until their pool of prospective combatants is practically exhausted. That appears to occur when about 30% of military-age men have been killed.

The ambitions raised up by mass armies could not be contained easily. The Napoleonic Wars killed (by my back-of-the-envelope estimate) about 30 percent of military-age Frenchmen, compared to the death of 28 percent of military-age Southerners during the Civil War. We do not have accurate demographic data for the Thirty Years’ War, but the casualty rate surely was of the same order. And that was true of our Civil War, when the South fought for slavery and empire. The Second World War killed about 30 percent of military-age Germans, who were convinced that the existence of the German nation was in jeopardy after the Versailles Treaty.

Casualties in such wars are not a regrettable side effect. They are the war’s raison d’être. They are tragic, in the strict sense of the word: Their terrible consequences arise from flaws that cannot be mitigated by compromise.

If Napoleon’s soldiers carried a field marshal’s baton in their rucksacks, the Confederates carried an overseer’s whip. Southerners had been fighting to expand slave territory in Texas, Kansas and other disputed territories for a generation. Most Southern soldiers, to be sure, fought for the same reason that most soldiers fight: They were ordered to do so. Even if most Southerners did not own slaves, however, many fought for the opportunity to acquire them. With respect to the motivations of the Confederacy, I refer to Professor Robert E. May’s classic The Southern Dream of a Caribbean Empire (1973). May cited hundreds of published Southern sources, of which this one is typical. On December 30, 1860, the Memphis Daily Appeal wrote that a slave “empire” would arise

from San Diego, on the Pacific Ocean, thence southward, along the shore line of Mexico and Central America, at low tide, to the Isthmus of Panama; thence South—still South!—along the western shore line of New Granada and Ecuador, to where the southern boundary of the latter strikes the ocean; thence east over the Andes to the head springs of the Amazon; thence down the mightiest of inland seas, through the teeming bosom of the broadest and richest delta in the world, to the Atlantic Ocean.

The above considerations do not vitiate the strong analogy between ancient Israel and modern America. On the contrary: Lincoln’s statement that God held both sides in the Civil War to strict account for their transgressions echoes John Winthrop’s warning that God would hold America to stricter account “because he would sanctify those who come near him.” We don’t like Lincoln—the actual Lincoln who perpetuated the slaughter until the South was bled dry—although we honor him in the service of national self-esteem. What we dislike in particular is Lincoln’s admonition that the destiny of the nations is in the hands of God, and that it is not within our power to remake the world according to our own preferences. That is the heresy that parades under such banners as Social Gospel, Progressivism, Wilsonian Idealism, or (in liberal Jewish parlance) tikkun olam, “repairing the world.”

Ancient Israel didn’t like Moses, either—a point well established in rabbinic commentary, although it is not often touched upon in Shabbat morning sermons. Lincoln summoned us to sacrifices that seemed too great to bear, and after his death we decided that we never would make such sacrifices again.

The National Covenant

Moses had told the Children of Israel that he would lead them to a land flowing with milk and honey. After ten of the twelve spies sent into Canaan returned fearful and disheartened, however, God determined that none of that generation except for Joshua and Caleb would enter the Promised Land. Korach incited a rebellion against Moses and Aaron, suppressed by a miracle when the earth swallowed the dissidents. There followed thirty-eight years of wandering in which God had nothing more to say to Moses, and the generation of the Exodus waited to die in the desert.

The 20th century’s preeminent sage of Modern Orthodoxy, Rabbi Joseph Soloveitchik, observed that in the portions of Numbers and Deuteronomy that recount the end of Moses’ life,

we are confronted with a touching tragedy—the tragedy of a teacher who was too great for his pupils, of the master who is too exalted, too deep, too profound for his generation. ….The failure of Moses to enter the land changed Jewish history, because had he entered Eretz Yisrael, the people never would have been exiled. Moses would have been anointed as the Messiah. Jewish history would have found its ultimate fulfillment and realization. If Bnei Yisrael had proven themselves worthy of communing with Moses, of being his disciples, if they would have had the receptive intellectual and emotional capacity to absorb Toras Moshe [the Torah of Moses[ immediately, then Moses would have entered and conquered the Promised Land….Moses was ready to be the Messiah. However, the Messianic era depends on the people being ready as well.

Rabbi Soloveitchik adds:

When he was told that he would not enter Eretz Yisrael, Moses pleaded for forgiveness. Had the people joined him in prayer, the Holy One would have been forced to respond. But they did not join…It was not the fault of Am Yisrael [the people of Israel] that Moses made a mistake. But had the people possessed the sensitivity and love for Moses similar to that love that Moses felt for them, they would have torn the decree into shreds. It was their fault. “Lema’anchem.”

If we had rallied to Moses at the plains of Moab, Soloveitchik adds, all the subsequent tragedy of Jewish history would have been avoided. Israel was punished for its sins by exile. America was punished for its sins by the Civil War. Israel still has God’s eternal promise; the United States of America has only the contingent claim to Divine favor of those who emulate Israel. As Rabbi Meir Soloveichik writes, “America’s covenant was self-initiated, and it can lose its exceptional nature, cease to be what it has been, become something else entirely. Without a rededication to the covenant of the United States, America as America will come to an end.”

By definition the notion of Election implies a special relationship between God and the United States of America. The thrice-daily Jewish prayer service concludes with Zechariah’s hope that one day all of humankind shall call on God by his right name, but Jews are asked to advance this goal by example rather than by proselytizing. We should read Lincoln’s declaration that America “held out a great promise to all the people of the world to all time to come” as an apocalyptic hope rather than a Wilsonian policy prescription. In the three decades since the collapse of Soviet Communism, we have spent trillions in a failed effort to make the world safe for democracy, and neglected our industrial base, our infrastructure, our educational standards, and our technological edge. In our naiveté and narcissism, we have nearly lost what makes possible Lincoln’s “great promise”—the example we set for the rest of the world.

Originally published by Law & Liberty.

Twitter

Twitter

Facebook

Facebook