Mission Compromised? The Advance of DEI at Notre Dame

Click here to view a PDF version of this article.

Executive Summary

The University of Notre Dame is among America’s finest. It is a trusted name. It has maintained a strong Catholic identity. Hiring Catholic faculty has long been important. Catholic students flock there. The mission of Notre Dame, however, is threatened by DEI practices that compromise Catholic doctrine and replace superb instruction with social engineering. According to its Board of Trustees Task Force, the school is undergoing “a profound shift from diversity, equity, and inclusion being ‘good to have’ to becoming a moral imperative.”[1]

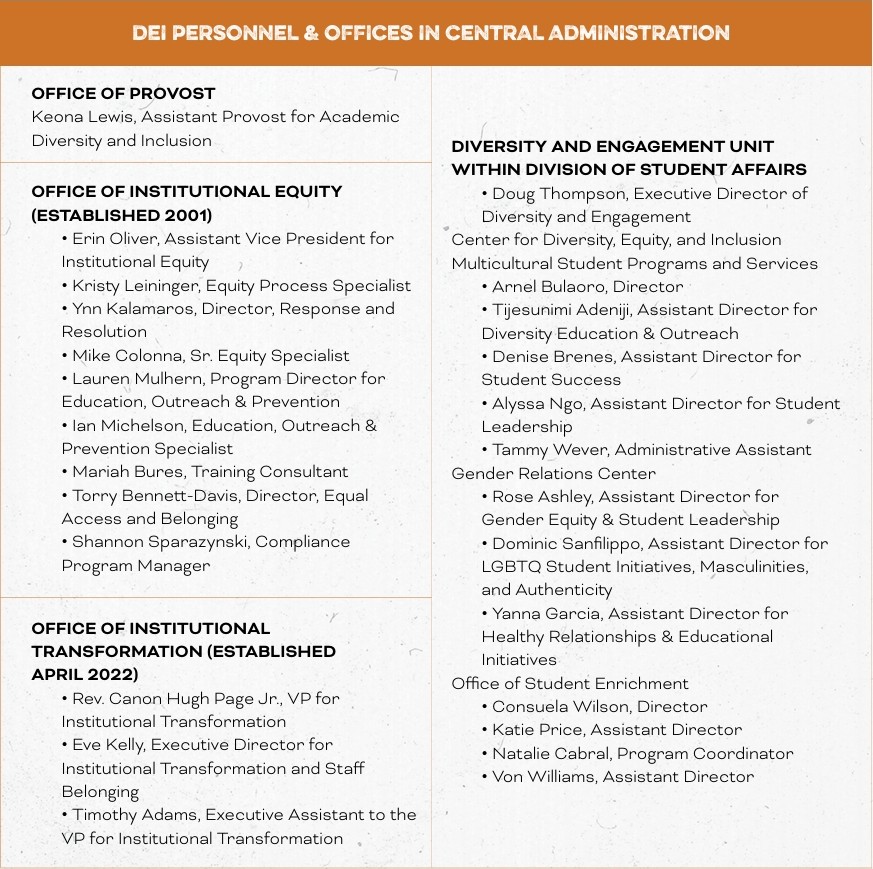

This report documents the steady construction of DEI at Notre Dame in recent decades. “Every division of the University, school, and college,” according to the Task Force in June 2021, “developed a diversity and inclusion plan” prior to 2020. Notre Dame already set goals and timetables for hiring ethnic minorities and women in the late 1970s (see below, Section 4). The Office of Institutional Equity, established in 2001, oversaw minority preferences in faculty hiring. Each college had diversity officers focused on monitoring job searches for adequate minority representation. Notre Dame’s Gender Relations Center (GRC), which opened in 2004, brought LGBTQ+ advocacy to campus.

Notre Dame hit the gas pedal on DEI in 2020. The Task Force wanted the school to “establish a structure that [would] ensure university-wide oversight and central leadership for the growing number of diversity and inclusion initiatives.” The Office of Institutional Transformation (OIT), established in April 2022, provided that structure. OIT works with staff across the campus “to implement an integrated diversity, equity, inclusion and justice strategy” and to “dismantle . . . systems of injustice.” The Center for Diversity, Equity and Inclusion, opened in fall 2023, aims to “enhance diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts at Notre Dame,” while also housing the GRC, the Multicultural Student Programs and Services, and the Office of Student Enrichment. Dedicating an office to institutional transformation shows astounding ambition. DEI is sown into the core of Notre Dame’s 2033 Strategic Framework. Recently, Notre Dame’s provost announced in an email that increasing “the number of women and underrepresented minorities on our faculty” is a goal “equally important” as increasing the number of Catholic faculty. That’s transformation.

Notre Dame expends much effort on DEI. Notre Dame employs about thirty DEI administrators, and according to estimates, spends more than six million dollars on DEI salaries. Notre Dame put on 167 distinct DEI events during the 2024 calendar year, including thirty-five events in September and October. Four agencies on campus are responsible for “welcoming” or creating a sense of belonging for minorities. Campus Ministry now practices racially segregated first-year retreats— “The Plunge: Black First-Year Retreat”—as well as retreats for Asians and Latinos. The Klau Center runs a program “Building an Anti-Racist Vocabulary” to restructure how people think in terms of systems of oppression. Notre Dame should revisit how its new DEI mission compromises its Catholic mission before DEI overshadows everything else.

Section 1: DEI in the Catholic Context: Separating the Wheat from the Chaff

Catholic Identity Meets Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion

Units across the Notre Dame campus claim that “the commitment to diversity at Notre Dame is inextricably tied to our Catholic mission, which calls us to respect the dignity of every person, to work toward the common good, and to stand in solidarity with the most vulnerable and marginalized members of our community,” as the College of Arts & Letters writes.[2] Similar statements pepper the 2021 Board of Trustees Task Force on Diversity, Equity and Inclusion report. Since Notre Dame “as a Catholic university” is “committed to defending the dignity of every human person, to promoting a just society in which every person can flourish, and to attending particularly to the needs of the most vulnerable,” it must “address [the] racism, inequality, and discrimination” manifest in various forms of disparity. “True inclusivity” is a “credible witness,” this new version of Catholic theology contends, and therefore a natural extension of the Catholic mission. The Task Force finds support for such sentiments in Notre Dame’s mission statement and in the Constitution of the Congregation of Holy Cross. “Our Catholic mission,” writes the Task Force, “animates our DEI efforts.”

Not everyone agrees that DEI policies and Catholic social teaching are synonymous. Ed Feser, for instance, a Catholic philosopher, argues that the animating ideology of DEI “is a grave perversion of the good cause it claims to represent, and it is utterly incompatible with Catholic social teaching.”[3] The late Father James Schall, who taught at Georgetown until 2012, worried that the modern emphasis on diversity portends the disintegration of the body politic, the universal church, or any institution that embraces it. While celebrating diversity, “we do not seek truth or unity or agreement or the common good.”[4] Bishop Robert Barron also sees the modern concept of diversity as corrosive of any Catholic institution’s mission and integrity. Often, DEI policies bespeak a fundamental rejection of the existing social order. They contain accusations that the university or the country are fundamentally and inescapably white supremacist or homophobic. Not infrequently, such accusations are leveled at Catholic institutions particularly and Western civilization more generally. Clear thinking is necessary to determine how DEI poses a threat to Notre Dame and any other Catholic institution.

The task of clear thinking is complicated since the words “diversity,” “equity,” and “inclusion” are ambiguous. DEI begins with sweet-sounding, civically engaging, innocuous-seeming, even churchy words of promise. Everyone wants to include others—certainly few want to exclude or to be unwelcoming based on hostility or “hate.” Excluding people from the chance to attend mass or to participate in the economy is unjust. No one wants to deny opportunities to others, so inclusion is, sometimes, used synonymously with spreading opportunity. All faithful, decent people treat others fairly and decently—equitably, according to their merits. Diversity or variety is found in our rich social and natural orders—and reducing such diversity to uniformity would require assertions of totalitarian powers that are deemed to be almost Soviet in scope. Education may even require some diversity.

Diversity, equity, and inclusion, however, even when understood as sympathetically as possible, are not fundamental principles. Diversity, equity, and inclusion serve broader social goods such as justice. Members of any social order must share common goods that transcend individuals. A diversity that compromises such sharing would destroy a social order or an institution with a shared purpose. Inequities and inequalities arise from diversity of interests, abilities, and dreams, and trying to eliminate disparate outcomes would itself lead to Soviet-style totalitarianism.[5] Neither can inclusion be embraced without limits. A university is bounded within such limits, as is every social order. Therefore, social orders exclude those who do not qualify or who refuse to abide by its principles.

The real meaning of diversity, equity, and inclusion is revealed in implementation. Notre Dame’s actions cross the line and make diversity, equity, and inclusion into ends, not means. They flirt with full-scale condemnation of Western, Christian institutions.

Notre Dame’s concern for DEI is present, as we shall see, in the Office of Institutional Equity, demanding that the university measure existing pools of candidates or students against an “equitable” standard. Since the late 1970s, Notre Dame has set goals and timetables to increase minority representation in hiring and admissions. It measures itself against some standards. The student body was 3.4 percent black in 2021, but Notre Dame was still concerned with “closing the gap between aspirations and reality”;[6] 3.4 percent is not good enough; more recruitment is necessary. The same goes for the faculty. In each case, Notre Dame assumes that the disparity, the gap, between reality and aspirations is not the result of individuals making choices about their lives. Notre Dame holds itself responsible for that gap, apparently due to institutional racism or unconscious bias. In fact, evaluations of today’s Notre Dame presume an unidentifiable standard so that the university can never say that it has done enough. Notre Dame has also established an Office of Institutional Transformation to challenge and change the institution in the name of DEI.

The Notre Dame 2033: Strategic Framework has the same difficulty with standards. When discussing “efforts to diversify the faculty,” the authors of the framework suggest that efforts have proceeded with “fits and starts” and imply that the efforts have lacked “long-term commitment.” The university has had success, the authors note, in attracting Latino faculty. But the university has not had the same degree of success with blacks. The “aspirations for faculty and staff hiring and retention need to be articulated and programs to ensure an inclusive campus expanded. We must commit, again in the phrasing of the Trustee’s report [the Task Force], ‘to the long game if we are truly to become the university we aspire to be.’”[7] Notre Dame has been playing this long game. The university has maintained an organized effort to attract black faculty since the 1970s. The “fits and starts” have all been accelerations toward the same goal. The fact that Notre Dame blames only itself for the lack of any remaining underrepresented minorities reveals a surrender to the more radical, dangerous ideology within DEI.

Notre Dame has set up an anonymous reporting system on campus to identify and punish perceived microaggressions, as we shall see Section 4. Microaggressions are, in the words of the source book on critical race theory, “small acts of racism, consciously or unconsciously perpetrated, welling up from the assumptions about racial matters most of us absorb from the cultural heritage in which we come of age” in a supposedly white supremacist country like the United States.[8] On one hand, this reporting system is seen as part of what it takes to make for a welcoming environment. Anyone made to feel unwelcome through language perceived to be discriminatory can anonymously report the perpetrator to university officials. Punishing microaggressions, some of which are even, as the language of the report itself makes clear, “unconscious”—that is, unintentional—is supposed to produce a welcoming culture. On the other hand, the ideology that countenances accusations of a microaggression reflects a suspicion about the native culture that supposedly sustains such aggression. It makes the feelings of the aggrieved the standard for aggression, not the intent of the person. The whole concept of microaggressions is based on the idea that the heritage and context of the place is inherently racist or sexist or homophobic—in a word, bigoted.

DEI advocates at Notre Dame claim they build a welcoming culture, but that is because without their efforts, they insist, Notre Dame’s culture would be disdainful, discriminatory, and hostile. A welcoming culture would only be the result of institutional transformation, its advocates claim. They say they want equity in hiring, but that is because, we are told, underrepresented minorities would be considered with contempt in the absence of bureaucratic training and detailed plans and timetables to get minorities a fair hearing. They claim to want diversity, but they cannot say when diversity would be achieved. DEI advocates use “diversity” to advocate for an unceasing institutional transformation.

Notre Dame’s Campus Ministry sponsors separate retreats for groups of underrepresented minorities. It hosts an event called “The Plunge: Black First-Year Retreats,” as well as specific retreats for Asians and Latinos. It also hosts LGBTQ Retreats and “Social Justice Retreats.” Racially-segregated retreats are done in the name of true inclusion, as DEI officials understand the term. This effort to build a so-called inclusive campus that is meant to be in line with Catholic social teaching through Campus Ministry ends up subverting the principles of the universal church.

If Notre Dame DEI proponents are little different from those at the University of Michigan or Yale University, the context of DEI at Notre Dame is different. The university has a distinct mission. It hires faculty members with that Catholic mission in mind. It attracts Catholic students. There is more intellectual diversity at Notre Dame and thus more respect for free inquiry, albeit with a purported respect for Catholic teaching. DEI does not dominate as it does elsewhere (yet!), but DEI still is a foreign element at Notre Dame and should DEI ideology become more mandatory than it is today, it could well compromise Notre Dame’s mission going forward.

Why DEI is Detrimental in Higher Education

DEI has become the dominant ideology on many American campuses. A country based on the ideas of DEI will have a difficult time maintaining social order and a commitment to the common good. The same is true of universities or colleges, which are dedicated to learning, to excelling at research, to moral formation, to the preservation of the Western heritage, and to professional development. Around the country, critics of DEI policies note the following:

- DEI admissions and hiring practices can lead to injustice: less qualified candidates being given priority compromises the commitment to learning and research.

- DEI hiring at the administrative level can jeopardize the institution’s financial health and culture.

- Inclusion policies often lead to reporting systems, student self-censorship, faculty self-censorship, and a climate of accusation and repudiation as “victims” define the limits of acceptable discourse on campus.

- Certain research questions are ruled out when DEI dominates the campus and answers to research questions are confined to a narrow range of DEI-friendly opinions. Research on family life, for instance, is impossible to conduct within the confines of radical DEI establishments.

- A university’s non-DEI mission is compromised by elevating DEI, alienating clients, supporters, and students.

- The demand for nonessential, nonmissional programs on campus. Many Christian colleges, for instance have built gay-affirming centers on campus. It is one thing to accept that gays, too, as human beings are made in the image of God and that they, like all other sinners, should strive to live in Christ; it is another thing altogether to “affirm” their sexual inclinations and to construct their identity, a prideful one, solely on the basis of such inclinations.

- Campus protests against Israel as an outpost of Western Civilization and in favor of terrorist attacks.

- The wasting of time and money-chasing verification for a false ideology.

It is always bad to live according to lies. It creates practical problems, too. Judging an institution according to a false standard makes people within that institution spin their wheels, mistake the means for the end, and lose institutional vitality. Notre Dame experiences some of the problems normally associated with DEI. It certainly wastes money and mission, condemning itself in the false pursuit of ideological dreams.

Section 2: The DEI Timeline at Notre Dame

1978. Academic Affirmative Action Committee (AAAC) beings work, developing “frameworks and timetables” for diverse faculty hiring. Annual reporting commences.

Fall 1997. Provost directs the deans of the Colleges of Arts and Letters, Science, Engineering, Business, and the Law School to hire College Diversity Officers to implement faculty diversity hiring plans.

Fall 2001.Notre Dame creates Office of Institutional Equity.

Spring 2004. Fr. Mike Poorman, C.S.C., Vice President of Affairs, announces the creation of the Gender Relations Center.

Fall 2012. Notre Dame publishes the “Beloved Friends and Allies Pastoral Plan,” an “official pastoral plan for the support and holistic development of LGBTQ students.”[9]

2013. President creates oversight committee on Diversity and Inclusion.

Summer 2013. Gender Relations Center hires assistant director for LGBTQ student concerns.

2014–15. Gender Relations Center expands to five full-time staff members, a graduate student intern, and over seventy student leaders serving as FIRE Starters, Event Facilitators, Dorm Commissioners, and student workers.

April 2016. Notre Dame hires Pamela Nolan Young as director for academic diversity and inclusion.

September 2016. University statement on Diversity and Inclusion released by President Emeritus Rev. John I. Jenkins, C.S.C. at the President’s Annual Address to the Faculty.

Summer 2020. Board of Trustees appoints Task Force to study DEI at Notre Dame.

Fall 2020. The College of Engineering establishes a Diversity, Equity and Inclusion Task Force and publishes a report evaluating DEI in every aspect of the college. The College of Arts and Letters establishes DEI Committee

2021. College of Engineering appoints Yvette Rodriguez as Director of DEI in Engineering. The College of Engineering establishes a standing committee on DEI.

June 2021. The Board of Trustees Task Force publishes report on Advancing Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion at Notre Dame: A Strategic Framework.

October 2021. The School of Law hires Max Gaston as Director of DEI.

April 2022. Notre Dame hires Rev. Canon Hugh Page Jr. to head the Office of Institutional Transformation.

2022. Notre Dame begins building the Center for Diversity and Inclusion, which will host the MSPS and Gender Relations Center.

January 2023. Notre Dame hires assistant provost for academic diversity and inclusion, Keona Lewis.

2023. The Center for Diversity and Inclusion opens.

August 2023. The University publishes Notre Dame 2033: A Strategic Framework, which makes diversity, equity, and inclusion central to the university’s ten-year plan.

Summer 2024. Notre Dame hires Doug Thompson as Executive Director of Diversity and Engagement.

Section 3: Notre Dame DEI Administrators

Notre Dame has more than two dozen central administrators dedicated to promoting DEI. Equity is an overriding concern (the Office of Institutional Equity has nine employees), though the Office of Institutional Transformation (OIT), the newest office, has five employees as well. In addition, Notre Dame’s colleges and schools have twelve DEI administrators in total. Many departments have DEI directors as well. Notre Dame spends more than $6 million on DEI personnel across the university.

Many of the positions seem quite duplicative. The top positions within the DEI hierarchy have job descriptions that sound quite similar. Koena Lewis would be helping to create “an environment where faculty and staff feel a strong sense of belonging and respect and where differences are celebrated.” When Doug Thompson was hired in May 2024, the university announced that he would “nurture belonging and inclusion among all students while further engaging underrepresented voices throughout the Notre Dame community.”[10] Hugh Page in Spring 2022 was excited be “intentional and creative in investing our energies and resources if we are to become an inclusive and welcoming community.”[11] Eve Kelly, hired to assist Page in the Office of Institutional Transformation, will be “strengthening institutional transformation and diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives focused on staff and further leveraging staff engagement opportunities.”[12]

Notre Dame does not make most salaries public. Estimates are possible, assuming Notre Dame’s DEI positions are paid commensurate to relevant peer institutions. Top-line DEI officials make $300,000 on average. Several other offices are in the $80,000 to $125,000 range, while specialist and administrative work usually ranges between $60,000 and $75,000. (All estimates come from ZipRecruiter.) Notre Dame has five officials that fall into the first category, twelve directors or assistant directors in the second category, and nine below the director level who are either specialists or executive assistants. If we assume that 30 percent of salaries are spent on benefits, we conclude that Notre Dame spends approximately $4.5 million on DEI salaries at the university level. Programming budget and capital expenses are not included in the salary numbers.

Notre Dame Colleges & Department Personnel Dedicated to DEI, with DEI Highlights from Each College

Colleges also spend no small amount of money on DEI. Associate deans and directors make more than $180,000 per year, with an estimated total package exceeding $275,000. Notre Dame colleges have seven deans dedicated to DEI, and several directors, who make less but who carry the ideological mantle. Department directors probably take buyouts for their DEI roles, which amounts to about $10,000 per director. If faculty serving on DEI committees take buyouts, the cost is much, much higher, since there are so many department-level DEI committees. Notre Dame thus spends nearly $2 million on DEI salaries at the college level.

School of Architecture

Crystal Artis Bates, DEI Program Director & Alumni Engagement

DEI Highlight: “Our Inclusive Culture”: We proudly participate in the broader University diversity initiatives, including work with the Diversity and Inclusion Oversight Committee and the University Committee on Women Faculty and Students, as well employing efforts to increase diversity within our own hiring and admissions practices.

College of Arts and Letters

Ernest Morrell, Associate Dean for the Humanities and Equity

Diversity, Equity & Inclusion Committee (DEIC)[13] and Initiative on Race and Resilience.[14]

DEI Highlights: The Department of History has adopted a statement on Diversity and Inclusion,[15] while Philosophy has a Climate Committee and a statement on being a welcoming and inclusive community.[16] Theology, Art, Art History & Design, Film, Television and Theatre, Music, Anthropology, Economics, Political Science, Psychology, and Sociology[17] have all adopted various kinds of DEI or antiracism statements as well. Psychology has a DEI Committee,[18] while Sociology has a Committee for the Advancement of Diversity and Inclusion.[19]

Mendoza College of Business

Kristen Collett-Schmitt, Associate Dean for Innovation and Inclusion

DEI Highlight: MBA program is “integrating DEI throughout the curriculum” as well as seeking to increase “diversity within our community through active recruitment of diverse perspectives.”[20]

College of Engineering

Yvette Rodriguez, Director of DEI In Engineering.

James Scmiedeler, Associate Dean of Faculty Development and Diversity in Engineering.

College of Engineering Diversity, Equity and Inclusion Standing Committee.[21]

DEI Highlight: Every department has a director of DEI in the College of Engineering.

- Aerospace and Mechanical: Hirotaka Sakaue, Director of DEI.[22]

- Chemical And Biomolecular: Yamil Colon, Director of DEI.[23]

- Civil, Env. & Earth Sciences: Antonio Simonetti, Director of DEI.[24]

- Computer Science: Tijana Milenkovic, Director of DEI.[25]

- Electrical: Monisha Ghosh, Director of DEI.[26]

The Law School

Max Gaston, Director of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion

DEI Highlight: Global Awareness and Diversity are among the core Formation Goals the Law School sets for itself. The director of DEI in the law school has a podcast called the DEI Podcast with Max Gaston.[27]

The Graduate School

Jamila Lee-Johnson, Assistant Dean for Inclusive Excellence

DEI Highlight: DEI is a goal in the Graduate School’s Strategic plan, which aims to “increase diversity in our graduate student and postdoctoral scholar populations” and to “improve climate.”[28]

College of Science

College of Science Diversity Council

DEI Highlight: Half of the six departments in the College of Science have adopted a DEI statement or an antiracism statement (Biological Sciences, Chemistry and Biochemistry, and Physics & Astronomy), while Physics & Astronomy is the only department with a Diversity Committee.

Section 4: What Notre Dame’s DEI Administrators Do

DEI has been associated with a host of corruptions at universities nationwide. At least on the surface, the DEI machinery at Notre Dame does not seem to be different from other elite universities. Notre Dame has, as the timeline in Section 2 shows ramped-up DEI efforts, in several areas, since 2020. Its DEI hiring binge is notable. Notre Dame now spends more than $6 million on DEI salaries across the university and in the colleges, as Section 3 shows. That number is only a part of what DEI costs Notre Dame. Notre Dame’s most enduring DEI commitment is to minority hiring plans, an effort that began in the 1970s. It has borne, as we shall see, at best mixed results, but it has distorted the hiring process. In recent years, Notre Dame has undertaken a campus climate initiative that includes creating and supporting several offices and establishing a bias reporting system. We now turn to each of these in turn.

Notre Dame’s Minority Hiring Plans

The DEI apparatus at Notre Dame has been focused on minority hiring for nearly fifty years. At first, its efforts brushed up against the limits of the law, when it constructed goals and timetables for the hiring of women and minorities. Eventually, the law accommodated such an approach. Notre Dame then continued down the same road as most other universities. It has never built a minority-only fellowship program, as other universities have. Such programs are often illegal. But Notre Dame has designed programs so that it is much more likely that only minorities would be hired for the program in question.

Hiring at Notre Dame balances at least three concerns—excellence, mission-fit, and diversity. Tensions between excellence and diversity are often noted. Diversity can compromise Notre Dame’s Catholic mission. In the beginning, it seems, Notre Dame was more willing to compromise diversity and worldly excellence to serve its Catholic mission. The affirmative action regime has culminated in an effort, currently underway, to assert that Notre Dame’s commitment to diversity is “equally important” to is Catholic mission.

Notre Dame has a long-standing commitment “to increasing the presence of minorities, women, Catholics, and members of the Congregation of the Holy Cross on the teaching-and-research faculty,” as an affirmative action committee wrote in 2003.[29] The first phase of affirmative action began in the mid-1970s, when the university announced a commitment to achieving “academic excellence” within “the context of justice for all our minorities who in one way or another have never had an adequate share in the task here.”

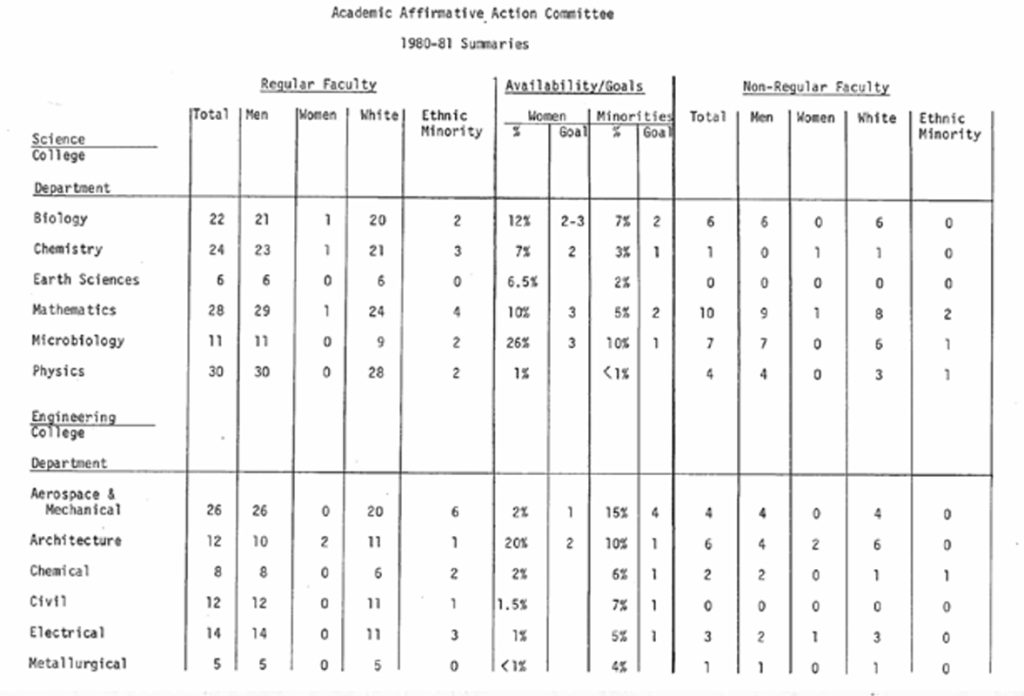

Over the course of the 1978–79 school year, the Academic Affirmative Action Committee (AAAC) set “five-year goals concerning regular appointment and timetables for meeting them.”[30] Faculty members pushed back against the affirmative action program during the 1970s and early 1980s. According to the committee, a faculty-wide “misunderstanding” about the program hampered its implementation. The program’s “goals” and “timetables” led faculty members to worry about “the appointment of unqualified persons to fill a quota.” Or perhaps the faculty then worried more about mission-fit than diversity. In any event, the AAAC complained about foot-dragging among the faculty. The committee only wanted “aggressive and imaginative identification and recruitment of qualified persons.” Most important for the affirmative action committee was stamping out “informal approaches” to hiring. By “informal,” apparently, the committee meant recommendations bypassing national searches in favor of students of friends within the Catholic network of scholars. In 1981, fourteen job searches were filled through this informal approach, and “fourteen white males were appointed.” Affirmative action demanded national job searches.

The AAAC reported on the composition of the faculty annually. It counted the number of women and minorities on Notre Dame’s faculty to measure success. It never reported on the number of Catholics among the faculty. In 1981, AAAC was disappointed that the number of women had declined by six, as had the number of minorities. (Asians were then considered minorities.) Each department had a goal for women and minorities. Biology, for instance, had 22 faculty. Its stated goals were to have two to three women and two minorities. It only had one woman and two “ethnic minorities.”

Table 1: AAAC Report on Science Departments, 1980-81

The 1987 report also discusses goals and includes tables: “One of the main goals of the Academic Affirmative Action Program is to encourage the achievement of approximate equivalence between the representation of minority persons on the faculty and their availability for appointment.” Availability is determined by “the percentage of minority persons and women prepared in the field.” Many science departments met or exceeded their recruitment goals for minority candidates (mostly because Asians were considered minorities, properly speaking, at that time). Only biology, earth sciences, architecture, and civil engineering missed their goals in 1987 for minority hiring.

Table 2: AAAC Report on Science Departments, 1987

The second phase expanded the earlier one. Faculty reluctance was no longer noted. In the mid-1990s, President Reverend Edward A. Malloy urged Notre Dame to “ratchet up our commitment” to affirmative action, just as Provost Nathan O. Hatch made “increasing the presence of women, racial minorities, and Catholic scholars” one of the six main priorities for academic life at Notre Dame. This ratcheting-up was institutionalized in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Notre Dame established The Office of Institutional Equity (OIE) and began appointing College Diversity Officers (CDOs) in the early 2000s. The director of OIE was to work with the CDOs and the AAAC to achieve the diversity mandate. Again, the concern for recruiting Catholic scholars was not part of the AAAC reports.

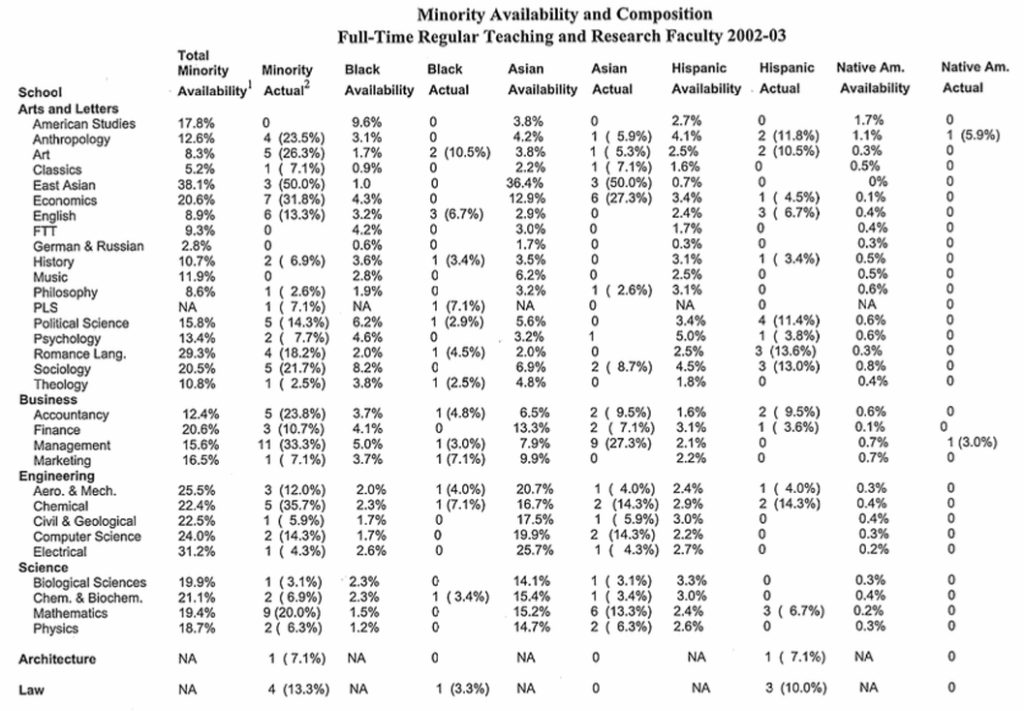

Notre Dame’s “ratcheted-up” commitment to affirmative action was based on a recognition that “adherence to a written policy of non-discrimination,” as the committee puts it, “will not, by itself, change the racial and gender composition of the teaching-and-research faculty.” More than mere “non-discrimination” would be necessary. More than establishing national searches would be necessary. More targeting and perhaps even a little discrimination would fill the gap. Setting specific goals for hiring blacks was especially important. Among the policies advocated for in the 2003 AAAC report are “specific strategic goals” to “double the number of African-American full-time teaching-and-research faculty” by 2012 and to expand and intensify the “efforts to recruit and retain faculty and students from historically underrepresented groups.”

Accomplishing these goals would require a more comprehensive accountability system. Departments would have to conceive of affirmative action plans that made “every reasonable effort” to get “highly qualified women and racial minorities in the faculty applicant pool.” A new threshold was passed under this plan. Every department at Notre Dame would conduct pool-analyses of diversity benchmarks for every job search. Departments would develop plans to increase the number of blacks/Hispanics and women in their applicant pools, including “publishing vacancy notices in minority professional periodicals” and “using the internet to identify so-called up and coming scholars.” Curriculum and job postings could be manipulated to attract minority candidates too. Africana Studies became a department in 2005, for instance, it seems, as a means of attracting black faculty members.

Department members were also meant to use their personal connections to encourage minority candidates to apply for positions at the university. Efforts to supplant personal connections with national searches turned into using personal connections within the context of national searches, as long as the personal connections helped expand diversity. CDOs would then analyze applicant pools for sufficient diversity, comparing the number of applicants against the supposed “availability” number to judge the adequacy of the job searches’ diversity action plan. Where the percentage of minority or women applicants in the applicant pool fell short of nationwide availability numbers, a new search could be ordered. The same process would be repeated when the department conducted interviews and made job offers. CDOs would submit annual reports to the OIE about diversity efforts during the year. In effect, departments would have to defend their decisions when they hired a white man or a nonblack person. The final report detailed “the total number of on-campus visits, as well as offers and acceptances by race and gender”; then the AAAC compiled all college reports into a statement on increasing the “ethnic and gender diversity of the faculty.” Its efforts extended to promotion and retention as well.

The AAAC reports simply count the number of women and minorities hired each year as well as on the total number of women and minorities holding positions at Notre Dame. In 2003, for instance, the Mendoza College of Business had six open positions. It brought “17 men and 9 women to campus for interviews, including 10 ethnic or racial minorities (9 Asians and 1 Black).” Departments extended five offers, four to men and one to a woman (two of the men were Asians). All candidates accepted the offers, though the woman delayed her employment for a year. The AAAC report is rife with such reckoning, with accompanying excuses when white men are hired in a particular college. In engineering, “the College made significant efforts to hire women and minorities over the past three years.” The law school “continues to explore strategies for attracting and retaining faculty from historically underrepresented ethnic or racial minority groups.”

Another major change was in the offing at this time. Asians would no longer count as ethnic minorities. Goals involved black and Hispanic faculty members, though disentangling Asian candidates from the “ethnic minority” categories would prove difficult during the next decade. As Table 3 shows, black, Hispanic, and Asian availability were still measured, and Asian numbers were no longer part of the overall strategic goals of the affirmative action committee.

Table 3: 2002-03 Report on the Number of Minorities at Notre Dame by Department

Total female teaching-and-research faculty was 23 percent in 2002–3, according to the AAAC report, while minority teaching-and-research faculty was now broken down into two different categories. The proportion of minority teaching faculty was just over 13 percent; the black proportion was 2 percent; the Asian was 6.6 percent; and the Hispanic was 4.5 percent. The percentage of blacks on the faculty would, over the course of time, be what really mattered.

The third phase intensified earlier plans yet again. In 2020, soon after the death of George Floyd, Notre Dame established a Task Force on Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion. Like its predecessors, it called for enhancing “the diversity of our faculty and staff,” but concern for female and Latino hiring was muted. “The data clearly evidence,” writes the Task Force, “that we are not yet who we want to be” owing to “unjust stereotypes, insensitivity, or ignorance,” as well as “past policies, practices, and decision-making.” The Task Force identified lacunae in the “ratchet” plan of the early 2000s. It would focus more on staff diversity. It would cease to use “availability” as a benchmark, instead adopting peer institutions’ numbers for comparisons (judging itself against AAU private institutions). It would bounce between concern for Catholic identity and concern for increasing the number of black bodies on campus. It would measure campus climate. It would put recruitment of minority students on the same level as the hiring of minority faculty and staff. Institutional Transformation—not just changes in the hiring practices—was necessary to attract black candidates to Notre Dame.

The Task Force found that previous efforts of minority recruitment had little effect. The percentage of black faculty hovered around 2 percent of the faculty both before and after the “ratchet” plan. Since the AAU average was around 3 percent, the Task Force thought Notre Dame as inadequate, as dropping the ball. The Task Force recommended that Notre Dame adopt “a cohort of faculty in a targeted area” where there are more likely to be “significantly more underrepresented scholars.” It should change its curriculum or build new entities on campus that were more likely to attract black candidates. Changing the standards for what counted as higher education at Notre Dame would present more opportunities for hiring blacks. To accomplish this goal, according to the Task Force, Notre Dame should use the model of Africana Studies, a self-standing department since 2005, with eight black faculty members.[31] It could expand that department or build other departments based on the same principle. It could establish a school of education designed to promote equity. Religious Studies could add a new emphasis on the black Protestant tradition. Other black faculty members have been recruited to serve in the administration and hold part-time appointments in new Notre Dame centers and institutes, like the Center for Social Concerns (one black administrator on the faculty) and the Klau Center for Civil and Human Rights.

Notre Dame also could set aside money for “strategic” diversity hires. Departments that do not have any current academic needs could, under this plan, petition to the provost for a faculty line if the line would enhance diversity at Notre Dame, presumably without much of a job search. This would encourage faculty be entrepreneurial in seeking out minority candidates so that they can grow their numbers. It is not clear if or how many faculty have been hired pursuant to such policies.

Another crucial part of the institutional transformation necessary to attract minority job candidates was a profound change in the campus climate.

Campus Climate Change

Notre Dame has sought to build what has come to be thought of as a more inclusive environment in three broad ways over the past two decades. First, Notre Dame has established centers and institutes for affinity groups, including the Gender Relations Center (established in 2004 and expanded since), the Multicultural Student Programs and Services, and the Center for Diversity and Inclusion (est. 2024). Second, Notre Dame has set up a reporting system on campus to ferret out perceived discrimination, harassment, and microaggressions. Third, Notre Dame has undertaken new initiatives pursuant to the 2021 Task Force Report. Among the results of these efforts is the Office of Institutional Transformation, as well as even more affinity-group centers and institutes on campus. OIT and other affinity-group centers put on unbelievable levels of programming around campus. In 2024 alone, there were 167 distinct DEI events on campus (repeated events are only counted once), averaging nearly fourteen DEI events a month. Indeed, the months of September and October 2024 each had thirty-five distinct DEI events.

While some of these policies and offices have been in place for years, others have been added pursuant to the Task Force Report in 2021. That the Task Force felt the need to tackle campus climate is notable. The Task Force investigated Notre Dame’s campus climate and found that it was pretty good. The questions were posed in the aftermath of the George Floyd riots. More than 85 percent of Notre Dame’s ethnic minorities felt “very satisfied” or “generally satisfied” with the sense of community on campus, as compared to a 71 percent average at peer institutions. This was quite satisfactory. For decades, more than three out of four minorities at Notre Dame would recommend the school to other students; this indicated a level of satisfaction that was above the national average at comparable colleges and universities too. After 2020, however, ethnic and racial minorities among Notre Dame’s Seniors turned a little sour on the place: only 53 percent were satisfied with the climate on campus at Notre Dame, while 64 percent were satisfied at peer institutions. This was held to betoken a crisis on campus demanding transformation. There was some evidence that ethnic and racial minorities among Notre Dame’s faculty were a bit less satisfied than their white colleagues as well. Based on these findings, the Task Force recommended the creation of new offices and the undertaking of new initiatives. First among these was the Office of Institutional Transformation

Offices & Affinity Groups

Office of Institutional Transformation

The mission of the Office of Institutional Transformationis to “dismantle . . . systems of injustice and create . . . space for those who have traditionally been excluded.” The office works with staff across the campus “to implement an integrated diversity, equity, inclusion and justice strategy.” The office gives consultations to units on campus about how they can advance DEI and become “more welcoming.” The office runs a “DEI practitioners group,” which consists of 160 faculty and staff members working to embed DEI into every area of the University. The office provides biweekly meetings training members in DEI practices and strategies. In partnership with the provost’s office and Human Resources, the office hosted the Inclusive Leadership Colloquium Lecture Series (ILCLS) for faculty and staff; this provided even more DEI training. Training sessions included subjects such as “From Equity Walk to Equity Talk: Expanding Practitioner Knowledge for Racial Justice in Higher Education” and “My Path to Anti-Racism as an Asian American Educator.” (For a complete list of DEI events see Appendix 1.) The office also hosts the Speakers Bureau, which features Notre Dame faculty and staff who conduct talks internally and externally on DEI topics. The office delivers “workshops on Notre Dame’s diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) strategy [and] facilitate[s] in-person and online professional development opportunities.”[32]

The Office of Institutional Equity

The office claims to uphold the university’s “Spirit of Inclusion.” The office is chiefly concerned with promoting affirmative action in faculty hiring, staff and administrative hiring, and in student recruitment. Its nine-person staff provide consultation, training, and resources to the campus community regarding equal opportunity, affirmative action, diversity, preventing discrimination and harassment, and retaliation; compliance with federal law and mechanisms for responding to complaints of discrimination, harassment, and retaliation. The staff also oversee the bias reporting system (discussed below). People who run these programs must report in their faculty evaluations about how their programs are meeting the demands of diversity, though it is not yet clear how or whether such reporting affects resource allocations or prestige. In a 2021 interview, then Vice President and Associate Provost for Faculty Affairs Maura Ryan did not deny that “diversity, equity and inclusion goals are an integral part of [professors’] annual performance goals,” though she implied that department heads and program leaders were the ones more likely to be judged based on diversity standards.[33]

Welcoming Redundancy: The OIT shows units on campus how to become “more welcoming.” The MSCS hopes to “nurture a sense of belonging.” The Center for Diversity provides a “safe and welcoming environment where students can foster a culture of belonging,” The Office of Student Enrichment wants to build a “welcoming” environment for underrepresented minorities at Notre Dame. Is Notre Dame so unwelcoming that it needs four units dedicated to “welcoming”?

Center for Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion

The Center for Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion provides a “safe and welcoming environment where students can foster a culture of belonging,” and enhances “diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts at Notre Dame.” The office provides space for students utilizing resources in Multicultural Student Programs and Services (MSPS), the Gender Relations Center (GRC), and the Office of Student Enrichment (OSE). Additional student organizations housed in the Center include the Diversity Council of Notre Dame (DCND), which explores the issues of diversity and inclusion at the university, and PrismND, Notre Dame’s official LGBTQ undergraduate student organization. Several of these affinity group centers deserve separate treatment.

Multicultural Student Programs and Services (MSPS)

The MSPS is committed to furthering DEI on campus. Its mission is to “nurture a sense of belonging, student success, and servant leadership for Notre Dame’s historically underrepresented students through growing relationships rooted in Catholic Social Teaching.” MSPS provides special services, such as student success initiatives, cultural enrichment programs, student clubs, and student organizations, to minority students. For example, the office provides several racially and ethnically segregated clubs, including the Africa graduate club, the Africana Studies club, the African Student Association, the Black Business Association, the Association of Latino Professionals in Finance and Accounting, the Black Cultural Arts Council, the Black Graduates in Management Club, the Black Graduate Students Association, the Black Law Students Association, Black ND Capitol, the Black Student Association, the Latinx Student Alliance, and many others. The office delivers various workshops to students, such as MiND (Microaggression Intervention at Notre Dame), a workshop to train students on how to maintain a “welcoming space for all students.” It includes the topics of race, racial microaggressions, and how to “become active bystanders when racial microaggressions occur.”

The Gender Relations Center (GRC)

The GRC creates and delivers workshops in the areas of “Gender Equity and Intersectionality, Healthy Relationships, LGBTQ and Allies, and Masculinities and Authenticity.” Programs implemented by the office include “Women Lead,” “Allyship,” and “Take Time to Listen” for men. The office trains “FIRE Starters,” who are students who help train other students in gender ideology and plan GRC events and programming. The GRC has four dedicated staff members and nine student fellows or assistants. The GRC skirts ND’s Catholic identity with events that seem to affirm the legitimacy of same-sex marriage and same-sex relations, but those administrators who attend events always couch their presence as celebrating the dignity of every human person as a child of God. Father Robert Lisowski, rector of Baumer Hall in 2021, cohosted a “Coming Out Day Celebration” with PrismND (Notre Dame’s official LGBTQ undergraduate organization) and attended the event wearing a rainbow stole.[34]

The Office of Student Enrichment (OSE)

The OSE is also dedicated to building a welcoming and inclusive environment at Notre Dame. The office primarily provides financial assistance to students, including illegal immigrants,[35] as well as first-generation and limited-income students.

Segregated Retreats: The Campus Ministry hosted racially segregated first-year retreats in 2024. It hosted “The Plunge: Black First-Year Retreats,” as well as specific retreats for Asians and Latinos. It also hosted LGBTQ Retreats and “Social Justice Retreats.”

Student and Faculty Events

Notre Dame puts on a huge number of diversity-themed events on campus. We have documented every DEI event at Notre Dame during 2024. A complete list of the events from January through June 2024 can be found in Appendix 1.

Reporting System

The Task Force of 2021 was concerned that Notre Dame lacks mechanisms “to properly address instances of discriminatory harassment and micro-aggressions.” Notre Dame adopted “Speak Up,” a behavior monitoring system that uses anonymous reporting, in 2015, after recommendations from the Diversity Council and the Division of Student Affairs. Today, the Office of Community Standards and the Office of Institutional Equity run “Speak Up” for students, staff, and faculty to report any “bias incidents,” which in fact hinders the development of the inclusive and tolerant climate university officials want to enforce, since it encourages an atmosphere of distrust, fear, and snitching. “All incidents of bias, discrimination and/or harassment” should be reported so that “the University can take appropriate action to assist the students involved and improve the campus climate.” [36] Notre Dame administrators are working to “raise awareness” about the tool. “All eyes need to be on it,” says one of its chief promoters in 2022. This reporting system helps “make our community a better place.”[37]

According to Notre Dame policy, “discriminatory harassment” is defined as unwelcomed conduct that is based on an individual’s or group’s race, color, national origin, ethnicity, religion . . . and that . . . creates an intimidating, hostile, or offensive University environment.”[38] The Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE) evaluates this policy as Yellow, which means that it is vague. According to FIRE, there is not a meaningful presumption of innocence for the accused; nor is there timely and adequate written notice, time to prepare with evidence, impartial fact-finders, a right to cross-examine, or a meaningful hearing process. Notre Dame receives an F (one out of twenty points) from FIRE on nonsexual misconduct, which is among the lowest mark in the nation.[39] “Believe all accusers,” it seems, is Notre Dame’s harassment policy, which cannot, by definition, be designed to create a freer, more inclusive campus climate. In Spring 2025, according to an email sent to faculty in January, Notre Dame is launching a “new online resource guide” for faculty and staff encountering “online harassment.”

Section 5: Balancing Catholic Identity & Diversity

Arguments about diversity in higher education often pit diversity against merit. There is a movement to replace DEI with Merit, Excellence, and Intelligence—that is, MEI—for instance, among classical liberals. That conflict, of course, is part of the story, but it is hardly the whole story.

The tension between Diversity and Catholicism runs through Notre Dame’s fifty-plus years of concern with increasing minority presence on campus. It complicates recruitment goals. It complicates timetables. On one hand, Notre Dame recognizes itself as a Catholic institution. This means having Catholics throughout the school’s administration, faculty, staff, and student body. A supermajority of students is Catholic (around 80 percent). In 2008, President Jenkins complained that the percentage of Catholic Notre Dame faculty had declined from 85 percent in the late 1970s (when affirmative action plans began) to 53 percent in 2008.[40] Every unit on campus is supposed to have at least 50 percent Catholics. On the other hand, Notre Dame judges itself by the standard of having an increasing number of blacks in the administration, staff, and faculty, as well as in the student body as a whole. Notre Dame cannot compare itself to Brown or Dartmouth or even to schools that have lost their Catholic identity (for the most part) like Georgetown and Boston College. Notre Dame is, in the words of its new strategic framework Notre Dame 2033, “the only religious university in the Association of American Universities.”[41] Joining the AAU is a mark of prestige, but it also risks changing the orientation of Notre Dame. Using AAU diversity goals instead of specifically Catholic goals in hiring may, when Notre Dame looks back at its history, prove a turning point in its loss of mission.

Why is attaching Notre Dame to the AAU a risk? Only a passingly small percentage of American Catholics are black—around 2 percent. Only about 4 percent of Catholics in the United States are Asian.[42] Efforts to hire Catholic faculty or recruit Catholic students mean drawing from a predominantly white and Hispanic pool, so the effort to emphasize diversity (which, in effect, means hiring blacks) runs up against Notre Dame’s stated aim of seeing that its faculty members are predominantly Catholic. Notre Dame’s provost recently noted this tension when he claimed that achieving diversity among faculty is “equally important” as maintaining Catholic identity. These goals are not the same, no matter how much ideologues wish away the tension between the two. What happens when the two goals clash? When can Notre Dame conclude that it has “done enough” to increase minority representation? What is an appropriate benchmark?

At no time in the past fifty years has the percentage of black faculty exceeded 4 percent of the faculty. According to the Task Force, the percentage of black faculty has fluctuated between 1.8 percent and 2.4 percent since 2009. This puts Notre Dame in the lower half of AAU Private Schools, which includes Duke, Stanford, USC, Emory, Cornell, and many other non-Catholic schools. Is the AAU benchmark appropriate for Notre Dame, if it seeks to keep its Catholic identity? The Task Force weighs in on this question thus:

Our Catholic mission compels us to assemble a more diverse community, reflective of the Church, our nation, and the world. Notre Dame should aspire to be the most successful university in the U.S. in attracting highly talented Black, Hispanic/Latino, Asian America and Native American Catholic students, faculty and staff.

Yet the report never compares Notre Dame’s faculty diversity to other Catholic schools. Perhaps Notre Dame has already accomplished this goal. Perhaps further measures are not needed.

Much the same could be said of the recruitment of black students. Since 2010, the percentage of undergraduates identifying as black has hovered between 3 and 4 percent, according to the Task Force. This proportional percentage exceeds the percentage of blacks who identify as Catholic in the country. Yet the Task Force predictably concludes that more must be done to recruit and retain black students. Among its suggestions are more scholarships, based on the assumption that “highly competitive” blacks are underenrolled at “elite institutions” owing to “a perceived lack of financial support.” “Improved communication and outreach” are necessary to attract more black college applicants to Notre Dame. “Recruiting a broader array of Catholics to Notre Dame is important, as we should reflect the vibrancy and diversity of Today’s Church in the U.S. and globally,” the Task Force intones. The Task Force never acknowledges that only 2 percent of American Catholics are black. Its members simply contend that the twin goals of Diversity and Catholicism “need not compete with, and indeed are complementary to” one another (emphasis supplied).

Notre Dame’s new strategic framework adopts the same doublespeak. The provost’s recent announcement that diversity is “equally important” at Notre Dame as Catholic identity is among the most concerning developments. Notre Dame is more diverse than it once was but “it is less diverse in the gender, ethnic, and racial makeup of its faculty staff, student body, and leadership team than it is called to be as the world’s leading Catholic university.” This way of framing the matter implies that there is an end point—a place where Notre Dame is “called to be.”[43] But no one can ever identify the end point. “Where we are today” is never adequate and “more” is always demanded.

Conclusion: Notre Dame & the DEI Counterrevolution

Notre Dame is not the institution it was fifty years ago. Notre Dame is much more of a research university. It has reached notable levels of prestige, including admission into the AAU. Its law school is now ranked in the top twenty. The student body is still predominantly Catholic, though the faculty members are much less so. Some continuities can be overstated, too. The liberal arts core has not changed a great deal, but the content of the courses has drifted according to academic fashions, almost all of which are at least explicitly secularist or at least anti-Christian, leftist, or socially and politically progressive in bent.

There is probably less a sense in official circles that Notre Dame’s Catholic identity is under siege today than there was two generations ago too. None of the strategic documents betray a worry about Notre Dame’s Catholic identity. No strategic objective indicates serious concerns about increasing the percentage of Catholic faculty members. The failure to mention this objective is an ambiguous fact. Has the school accommodated the forces of late modernity, or has it successfully warded them off?

The build-out of Notre Dame’s DEI infrastructure should in this sense be a cause for worry. It is an indication of where the university is heading. DEI demands a root-and-branch rejection of inherited categories and a limitless transformational promise into a Beloved Community. It may appear to be in accordance with Catholic social teaching on the outside, but it is Paulo Freire—radically Marxist critical pedagogy—on the inside. Every document is carefully constructed not to disappoint the most extreme diversity advocates, while maintaining the façade of orthodoxy. In fact, with time, the continual expansion of DEI may well corrupt Notre Dame’s ability to transmit genuinely Catholic teaching from one generation to the next.

On the other hand, the DEI infrastructure may be just an expensive virtue signal. Much is uniquely good at Notre Dame. Notre Dame still actively seeks to hire faculty and to admit students aligned to the Catholic mission. Notre Dame has had no notable free speech incidents since a speech by Michael Knowles was canceled owing to security concerns in 2019. (Notre Dame has relatively low scores on free speech from national organizations.) No one on the outside knows exactly how DEI policies and trainings distort job searches. If they do not distort it, then the infrastructure is not needed. If they do distort them, then the question must be asked: How much does diversity compromise the unique Catholic mission and Notre Dame’s institutional excellence? Nor does Notre Dame publicize its admission statistics, so it is impossible to know if minority students are held to the same admission standards as others. Yet DEI infrastructure does not stay voluntary for long. It represents a dangerous foreign ideology at America’s leading Catholic institution of higher education.

Institutions across the country are rolling back their commitments to DEI. They find that it creates a toxic work environment, that it is costly, that it is counterproductive, that it does not yield the results it claims to deliver. Notre Dame has four centers on campus dedicated to creating a more welcoming environment for underrepresented minorities. An annual survey about whether such efforts are worth it might be pursued. How many people even attend the 167 DEI events on campus? Is this overkill? The Office of Institutional Transformation is only two years old. It could be shuttered, its budget allocated to another worthy mission. Notre Dame could commit itself to race-blind hiring and admissions. It might revisit the decisions to invest so much prestige and money into diversity. Would Notre Dame be worse if this DEI infrastructure simply disappeared?

Appendix 1

Table 4: Number of Distinct DEI Events each Month, 2024

Diversity Events Jan. 2024-June 2024

Martin Luther King Jr. Day of Service (Law School)

Annual Candlelight Prayer Service

Lunch and Learn Workshop: “Inclusive Teaching With Canvas”

Lunch and Learn Workshop: “Inclusive Teaching With Canvas”

Research That Matter—DEI Lightning Talks

Walk the Walk Week: Staff Unity Summit

Panel Discussion: “Continuing the Conversation— ‘Walking in the Spirit of Truth: Charting the Pathways to Racial Justice, 2.0′”

International Holocaust Remembrance Lunch Lecture: “The Philosophy and Praxis of Dr. Janusz Korczak: Pioneer Champion of Children’s Rights and Child-Centered Pedagogy”

Arts of Dignity Student Art Exhibition: Opening Reception

Inclusive Leadership Colloquium Lecture Series—”Building the Beloved Community: Perspectives”

Film: Frybread Face and Me (2023)

Film Screening of Fannie and Commentary by Filmmaker Christine Swanson, ’94 alumna

Lecture—”African American Classical Architecture: Then and Now”

The Notre Dame Chorale (Singing Music in Nine Foreign Languages)

Film: INAATE/SE/ (2016)

Panel Discussion—”Avoiding Harm: A Muslim Response to Covid-19″

Dance Theatre of Harlem (afternoon performance)

Film—John Lewis: Good Trouble (2020)

Film: Songs My Brother Taught Me (2015)

Discussion—”Sacred Lands: Apache Stronghold v. United States of America”

Lecture and Book Discussion—“From Equity Walk to Equity Talk: Expanding Practitioner Knowledge for Racial Justice in Higher Education” (Part of the Inclusive Leadership Colloquium Lecture Series)

Panel Discussion: “Antisemitism and Other Hates”

Concert—”Cosmic Wonder”: Bach, Montgomery, Haydn with new Sacred Music Chamber Orchestra and Soloists

Lecture—“Gender, Justice and Joy: Legal Travels through the Patriarchy, Suppressed Speech and Corporate Crime”

Film and Panel Discussion: Three Chaplains

Lecture—”Making the MexiRican City: Mexican and Puerto Rican Migration, Activism, and Placemaking in Grand Rapids, Michigan”

The 26th Annual Dialogues on Nonviolence, Religion and Peace

Signs of the Times Discussion Series: “Diversity & Inclusion in South Bend”

Films and Discussion—Colombian Connection: State Violence Shorts

Diversity, Equity and Inclusion “Grow the Good in Business™” Case Competition

Documentary—The Pendleton 2: They Stood Up

Interfaith Flower Planting and Conversation—”Looking Towards Earth Day: Care for Our Common Home from Youth and Multifaith Voices”

Panel Discussion—”Combating Human Trafficking: Current Challenges and Concrete Solutions”

Discussion—”Migration and Catholic Social Teaching: Welcome, Protect, Promote, and Integrate”

Lecture and Discussion: “My Path to Anti-Racism as an Asian American Educator” (Part of the Inclusive Leadership Colloquium Lecture Series)

Film: The Catskills (2024) (Part of the Michiana Jewish Film Festival)

Film: Kidnapped (2023) (Part of the Michiana Jewish Film Festival)

Film: Seven Blessings (2023) (Part of the Michiana Jewish Film Festival)

Film: Vishniac (2023)

Film: The Monkey House (2023) (Part of the Michiana Jewish Film Festival)

Film: Running on Sand (2023) (Part of the Michiana Jewish Film Festival)

Mural Celebration at Foundry Field

South Bend Pride Festival

Juneteenth

Community training: Addressing homelessness and providing support

UZIMA! Drum and Dance presents Boundless

[1] Office of the President, Rev. A. Dowd, C.S.C., Notre Dame Board of Trustees’ Task Force Report on Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion: A Strategic Framework, University of Notre Dame, June 2021, https://president.nd.edu/presidents-initiatives/notre-dame-board-of-trustees-task-force-report-on-diversity-equity-and-inclusion/.

[2] ”Building a Community Where All Can Flourish,” Diversity, Equity & Inclusion, University of Notre Dame, https://al.nd.edu/about/diversity-equity-and-inclusion/.

[3] Edward Feser, All One in Christ: A Catholic Critique of Racism and Critical Race Theory (Ignatius, 2022), 54.

[4] James V. Schall, “Diversity,” The Catholic Thing, February 9, 2010, https://www.thecatholicthing.org/2010/02/09/diversity/.

[5] Pope Leo XIII, Rerum Novarum, 17: “It must be first of all recognized that the condition of things inherent in human affairs must be borne with, for it is impossible to reduce civil society to one dead level. Socialists may in that intent do their utmost, but all striving against nature is in vain. There naturally exist among mankind manifold differences of the most important kind; people differ in capacity, skill, health, strength; and unequal fortune is a necessary result of unequal condition. Such inequality is far from being disadvantageous either to individuals or to the community. Social and public life can only be maintained by means of various kinds of capacity for business and the playing of many parts; and each man, as a rule, chooses the part which suits his own peculiar domestic condition.”

[6] Office of the President, Rev. A. Dowd, C.S.C., Notre Dame Board of Trustees’ Task Force Report on Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion: A Strategic Framework, University of Notre Dame, June 2021, https://president.nd.edu/presidents-initiatives/notre-dame-board-of-trustees-task-force-report-on-diversity-equity-and-inclusion/.

[7] Notre Dame 2033: Strategic Framework, https://strategicframework.nd.edu/assets/528836/notre_dame_2033_a_strategic_framework.pdf, p. 19.

[8] Richard Delgado and Jean Stefancic, Critical Race Theory: An Introduction, 2nd ed.n (New York University Press, 2017), 2.

[9] “Beloved Friends and Allies: A Pastoral Plan for the Support and Holistic Development of GLBTQ and Heterosexual Students at the University of Notre Dame,” University of Notre Dame, https://friendsandallies.nd.edu.

[10] Kate Morgan, “Doug Thompson Appointed Inaugural Executive Director of Diversity and Engagement,” University of Notre Dame, May 15, 2024, https://studentaffairs.nd.edu/about/news-and-events/news/doug-thompson-appointed-inaugural-executive-director-of-diversity-and-engagement/.

[11] Dennis Brown, “The Rev. Canon Hugh Page Appointed Inaugural VP for Institutional Transformation and Advisor to the President,” University of Notre Dame, April 27, 2022, https://news.nd.edu/news/the-rev-canon-hugh-page-appointed-inaugural-vp-for-institutional-transformation-and-advisor-to-the-president/.

[12] “Eve Kelly Named Executive Director for Institutional Transformation and Staff Belonging,” June 28, 2024, University of Notre Dame, https://transformation.nd.edu/news/eve-kelly-named-executive-director-for-institutional-transformation-and-staff-belonging/.

[13] “Diversity, Equity & Inclusion Committee,” University of Notre Dame, https://al.nd.edu/about/diversity-equity-and-inclusion/diversity-equity-inclusion-committee/.

[14] “Notre Dame Initiative on Race and Resilience,” University of Notre Dame, https://raceandresilience.nd.edu/.

[15] “About,” Department of History, University of Notre Dame, https://history.nd.edu/about/.

[16] “The Philosophy Department Climate Page,” Department of Philosophy, University of Notre Dame, https://philosophy.nd.edu/about/the-philosophy-department-climate-page/.

[17] “CADI Mission Statement,” Department of Sociology, University of Notre Dame, https://sociology.nd.edu/about/diversity-and-inclusion-statement/cadi-mission-statement/.

[18] “Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Mission Statement,” Department of Psychology, University of Notre Dame, https://psychology.nd.edu/about/diversity-equity-and-inclusion/.

[19] “CADI Mission Statement,” Department of Sociology, University of Notre Dame, https://sociology.nd.edu/about/diversity-and-inclusion-statement/cadi-mission-statement/.

[20] “MBA Diversity, Equity & Inclusion,” Mendoza College of Business, University of Notre Dame, https://mendoza.nd.edu/graduate-programs/the-notre-dame-mba/dei/.

[21] “Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion in Engineering,” College of Engineering, University of Notre Dame, https://engineering.nd.edu/about-the-college/diversity-equity-and-inclusion-in-engineering/.

[22] “Administration and Staff,” Aerospace and Mechanical Engineering, University of Notre Dame, https://ame.nd.edu/about-ame/administration-and-staff/.

[23] “Administration and Staff,” Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering, University of Notre Dame, https://cbe.nd.edu/about-cbe/administration-and-staff/.

[24] “Administration and Staff,” Civil and Environmental Engineering, University of Notre Dame, https://ceees.nd.edu/about-ceees/administration-and-staff/.

[25] “Administration and Staff,” Computer Science and Engineering, University of Notre Dame, https://cse.nd.edu/about-cse/administration-and-staff/.

[26] “Administration and Staff,” Electrical Engineering, University of Notre Dame, https://ee.nd.edu/about-ee/administration-and-staff/.

[27] Max Gaston, The DEI Podcast with Max Gaston, RSS.com, https://rss.com/podcasts/deipod/.

[28] “University Strategic Framework,” University of Notre Dame, https://strategicframework.nd.edu/college-school-division-plans/college-school-plans/graduate-school/.

[29] Notre Dame Reports, University of Notre Dame, Annual Report of the Academic Affirmative Action Committee for the Academic Year 2002–2003, 185 accessed at

[30] Notre Dame Reports, 1980–81, 205, University of Notre Dame, https://archives.nd.edu/ndr/NDR-11/NDR-1981-12-11.pdf.

[31] ”Faculty,” Department of Africana Studies, Notre Dame University, https://africana.nd.edu/people/faculty/.

[32] “Programs,” Office of Institutional Transformation, University of Notre Dame, https://transformation.nd.edu/programs/.

[33] W. Joseph DeReuil, “Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Goals: The Future of Notre Dame,” The Irish Rover, October 13, 2021, https://irishrover.net/2021/10/diversity-equity-and-inclusion-goals-the-future-of-notre-dame/.

[34] Mary Frances Myler, “No Man Can Serve Two Masters,” The Irish Rover, October 13, 2021, https://irishrover.net/2021/10/no-man-can-serve-two-masters/.

[35] “Dream ND Community,” Office of Student Enrichment, University of Notre Dame, https://studentenrichment.nd.edu/programming/for-undocumented-daca-students/.

[36] “Speak Up: Reporting an Incident,” Office of Community Standards, University of Notre Dame, https://perma.cc/W2X3-B8A3.

[37] Bella Laufenberg, “Explained: University Leaders Talk about the History and Purpose of SpeakUp,” The Observer, November 7, 2022, https://www.ndsmcobserver.com/article/2022/11/explained-university-leaders-talk-about-the-history-and-purpose-of-speakup.

[38] “Policies,” Office of Institutional Equity, University of Notre Dame, https://equity.nd.edu/equity-resources/sexual-and-discriminatory-harassment/policy/.

[39] “Private University: University of Notre Dame; Due Process Ratings” FIRE, https://www.thefire.org/colleges/university-notre-dame/due-process.

[40] Richard Conkin, “How Catholic the Faculty?” Notre Dame Magazine, Winter 2006–7, https://magazine.nd.edu/stories/how-catholic-the-faculty/#:~:text=We%20can%20succeed%20in%20advancing,85%20percent%20to%2053%20percent.

[41] Notre Dame 2033: A Strategic Framework, 3.

[42] Justin Nortey, Patricia Tevington, and Gregory A. Smith, “9 Facts about U.S. Catholics,” Pew Research Center, April 12, 2024, https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2024/04/12/9-facts-about-us-catholics/#:~:text=Most%20U.S.%20Catholics%20are%20White,discuss%20in%20more%20detail%20below.

[43] Notre Dame 2033: A Strategic Framework, 19.

X

X

Facebook

Facebook

Truth Social

Truth Social