Causing Contagion

This essay was originally published on March 13, 2023 by The American Mind.

Biden’s spending spree and Fed blunders started the bank crisis.

Bank runs are a classic symptom of excessive central bank tightening. The Biden Administration unleashed the worst inflation since the seventies by throwing $3 trillion of transfer payments at U.S. consumers after the economy had already begun to recover from the COVID recession. Unlike the inflation of the seventies, though, credit expansion was not the culprit—helicopter money and supply constraints were at fault. The Federal Reserve blundered by tightening credit conditions when credit wasn’t the problem.

The result was a whipsaw in the valuation of bank balance sheets that eventually took down Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank of New York. The aftershock will be a persistent squeeze on bank lending and tougher credit conditions for U.S. business. The stress will extend to European and Japanese banks, who have to roll over $13 to $14 trillion of liabilities to U.S. banks arising from currency hedges on overseas holdings of U.S. assets.

Monetary tightening is the wrong medicine. Today’s inflation is due to expansive fiscal policy hitting supply constraints. The correct remedy is to stop pouring gasoline on the flames—as Biden proposes to do in his profligate $5 trillion budget—and to increase supply by removing obstacles to manufacturing and energy investment in the U.S. I offered a plan for restoring American manufacturing in a new Provocations essay for the Claremont Institute’s Center for the American Way of Life.

Unlike all previous periods of stress in the banking system, the quality of bank assets isn’t an issue in the regional bank runs of the past week. During the COVID epidemic banks loaded up on the highest quality assets—bonds issued by the U.S. Treasury and U.S. government agencies—as the government showered $6 trillion in stimulus money on American consumers. That pushed inflation to the highest level since the late seventies, and the Federal Reserve responded by raising interest rates, reducing the market value of banks’ bond portfolios.

Bank holdings of government debt nearly doubled between 2021 and 2022 to a peak of $4.5 trillion, as banks financed the lion’s share of fiscal stimulus. Bond prices move inversely with interest rates, and the Fed’s interest rate hikes wiped $341 billion off the value of banks’ hold-to-maturity portfolios of $2.6 trillion. Banks don’t have to book those losses unless they sell their securities. Investors feared that a run against deposits would force banks to sell bonds and recognize those losses. That turned into a positive feedback loop in the case of Silicon Valley Bank.

Unlike the 2008 crisis, when dodgy bank mortgage lending and fantastic levels of leverage put the banks into a self-made crisis, last week’s bank tremors were the handiwork of the bungling U.S. government. By shoveling $6 trillion of consumer spending into an economy hamstrung by supply constraints, the Treasury unleashed a wave of inflation driven by a huge disconnect between consumer demand and production capacity. That left the banks to hold the Treasury’s bag and finance a large part of the largesse on their balance sheets.

The inflation of 2022 was like no inflation in the past, as I showed in an essay for RealClearPolitics. The last time the Consumer Price Index approached double-digit yearly growth, in the late seventies, a credit-fueled grab for hard assets drove inflation. But in 2021, $6 trillion in federal government consumer subsidies sparked a scramble for consumer durable goods. A demand shock hit supply constraints, and the price of used cars, electronic goods, and other items rose by record margins.

COVID drove consumers out of public transport into private cars and boosted demand for work-from-home electronics. Used car prices jumped nearly 50% year-on-year as of June 2021.

In 2021, the Federal Reserve insisted that there wasn’t any inflation, and if there was inflation it would be transitory. Instead, the U.S. endured the stiffest price increases since the early eighties. Now the Fed hawks want to push the central bank’s overnight rate to 5.5% or 6% from the present 4.75%. It’s too late to do good, but not too late to do damage.

In the late seventies, housing prices set the pace for inflation. Homes were the only U.S. asset class that outperformed inflation during the seventies, and consumers borrowed at double-digit mortgage rates as a wealth hedge against inflation. But in 2021 and 2022, durables led the inflation wave. The RealClearPolitics essay linked above offers an exhaustive examination of the data to support this conclusion.

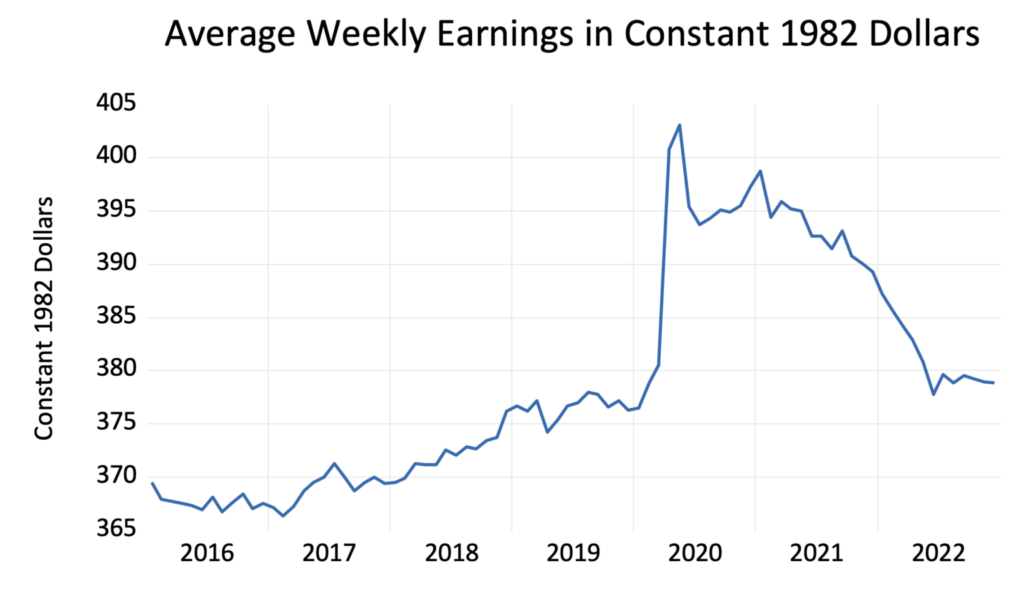

What did not drive inflation was wages. The Fed models focus on wage growth as a driver of inflation. But a simple comparison of leads and lags in CPI change and changes in average hourly earnings in the U.S. shows that wages lagged changes in CPI.

Average weekly earnings in December grew just 3.6% from a year earlier, in contrast to the more than 7% growth registered during 2021.

After inflation, average weekly earnings have been falling since 2021. That helps explain why employers are having trouble finding workers: Fewer Americans are willing to work for less pay.

The consumer boomlet is coming to an end. Inflation-adjusted retail sales are falling, and consumers have had to cover the gap between prices and wages with their credit cards. Revolving credit outstanding fell between January 2020 and March 2021, as consumers used part of the $6 trillion stimulus to pay down debt, but rose back to trend starting in May 2021.

There’s not much inflation out there. Leisure and hospitality prices are still rising, to be sure, but not the price of necessities or large-ticket consumer items.

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the only big driver of CPI inflation today is shelter, which comprises about a third of the index. Housing price inflation, though, is largely a statistical illusion. I was among the first analysts to show that the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ gauge of shelter inflation is about a year out of date. Because of the lag in the government’s reporting, the shelter component of the CPI probably will rise for the better part of a year even while housing prices fall.

Rent inflation was running at nearly 20% at the 2021 peak, but is now closer to 5% according to market-based measures like the Zillow or Apartmentlist.com indices.

Higher mortgage rates have already begun to deflate the housing bubble. Home prices hit a record in July 2022 but have been falling since them.

The $6 trillion stimulus is mainly spent, consumers are back to living on plastic, and retail activity is slacking off. As a result, we observe deflation in both durable and nondurable goods prices, as well as in current market measures of shelter.

Further monetary tightening at this point puts the cart before the horse. Worse, it will kill the horse, and leave the U.S. economy in a prolonged period of weakness.

Twitter

Twitter

Facebook

Facebook