Making Kindergarten Teachers into Radicals

Elementary Education at the University of Florida

Click here to view a PDF version of this article.

Executive Summary

Florida has been eliminating Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) offices and policies in higher education. The next stage of DEI regulation should involve K-12 teacher preparation programs, which are among the most politicized, ideologically captured departments in modern universities. States have the authority to regulate teacher certification requirements, and in turn shape the curriculum taught in higher ed K-12 training programs. The need is great.

Florida has been eliminating Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) offices and policies in higher education. The next stage of DEI regulation should involve K-12 teacher preparation programs, which are among the most politicized, ideologically captured departments in modern universities. States have the authority to regulate teacher certification requirements, and in turn shape the curriculum taught in higher ed K-12 training programs. The need is great.

This first-of-its-kind report provides a comprehensive analysis of the elementary education major at the University of Florida (UF), the largest education major within UF’s College of Education (COE) over the past decade. UF’s COE revolutionized and racialized its elementary education major after the 2020 Floyd riots. Most required classes now based on the idea that America is fundamentally and irredeemably racist, among other sins. As UF’s COE states in its curriculum change approval memorandum, “The state of our nation and global society leads us to conclude that emphasizing a social justice focus in our new program is important and much needed.”

During the COE’s revolution of 2020, professional classes emphasizing math content, teaching methods for music and art, core teaching strategies and basic classroom management were eliminated. UF’s new program was “centered on equity pedagogy.” Equity pedagogy makes raising racial consciousness and eliminating racial gaps—and not subject matter mastery or learning-effective teaching strategies—the moral imperative of the teaching profession. In UF’s elementary major, the assumptions of equity pedagogy are treated as matters of fact. Students are required to integrate equity pedagogic assumptions into their practice. The assignments lack rigor (nearly all focus on self-reflection about the teacher’s own biases) and emphasize how teachers, above all, must overcome their own racial and sexual biases.

More than half of the courses in the elementary education major are infused with critical pedagogy.

For Example, through EDG 3623: Equity Pedagogy Foundations, the first required equity pedagogy course, students are “prepared to leverage the assets of students and families from diverse backgrounds to engage in meaningful change in the classroom, community, and beyond.” The course’s objectives are inseparable from believing in and promoting critical pedagogy. Its two required readings are critical race staples in children’s literature. Further readings include books of critical race theory such as Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow, Peggy McIntosh’s “White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack,” and a seminal article devoted to these themes titled “Dismantling the School-to-Prison Pipeline through Racial Literacy Development in Teacher Education” by Yolanda Sealey-Ruiz. Such is the introductory course for elementary education majors!

More than half of the required courses in UF’s elementary education major are infused with critical race theory, radical gender theory, and other aspects of critical pedagogy, as detailed in this report through an analysis of course descriptions, course learning outcomes, required and suggested readings, and assignments. The emphasis on critical pedagogy even extends to math courses, as well as courses in school discipline and classroom management. At least ten of the twenty-four elementary education courses for majors—including all in the four-course sequence on equity pedagogy and two of the four prerequisites (which all undergraduates in the COE must take)—have critical pedagogy sown into every aspect of course design. An additional four courses have critical pedagogy sown into large parts of their course design, while fewer than half appear to be mostly devoid of critical pedagogy in their syllabi.

UF’s COE violates Florida House Bill 1291, passed in 2024, which regulates the teacher certification programs. Yet it does not have to remain like this. The COE could turn away from ideological approaches that contradict Florida’s laws. If COE does not change, we recommend ways to regulate teacher certification that will point teacher programs away from corrupt critical pedagogy models of education and create a more classical emphasis within Florida’s teacher body. Florida is once again leading the way in creating competent, patriotic education for K–12 students. Other states cannot afford to neglect this important area of policy and should take the evidence of this report as a warning that their K-12 educator training programs must also be audited.

The Problem of Teacher Preparation

Quality teaching matters. Effective teachers improve student learning; enhanced learning improves the quality of life for their students after they graduate. Yet teacher preparation programs are both ineffective and heavily politicized. The National Council on Teacher Quality labels schools of education “an industry of mediocrity.” Arthur Levine, the former president of Columbia Teachers College, thinks “the education our teachers receive today is determined more by ideology and personal predilection than the needs of our children.” The politicization of teacher preparation programs has intensified in the past forty years, such that there are few traditionalists left anywhere in schools of education.

Yet schools of education have been out of sight and out of mind for most education reformers. Most people assume that they impart to prospective teachers the content and pedagogical knowledge necessary to run a classroom effectively.

Not so. Those that have studied schools of education have concluded that teacher education programs are among the most highly politicized on the modern university campus. One study, from Jay Schalin of the James G. Martin Center for Academic Renewal, solicited education school syllabi from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill, and University of Michigan (among the three most prestigious) to discover which authors were most assigned for students to read. Topping the list were Gloria Ladson-Billings, Paulo Freire, and Linda Darling-Hammond—all of whom are advocates of radical, critical pedagogy rather than teachers of traditional professional techniques and strategies. Another study from David Steiner and Susan Rozen analyzed over 160 education school syllabi from sixteen major universities. They found a heavy emphasis on “constructivist and/or progressive” methods, readings from few traditionalists, almost all articles published in the past thirty years, and few programs emphasizing basic teaching skills at the expense of contemporary politics. A Wisconsin Institute of Law and Liberty published selections from syllabi at Wisconsin’s public university schools of education in 2022, showing that leftist political activism, critical race theory, and radical gender theory were the dominant motifs throughout the system.

The politicization of teacher preparation programs has intensified since the 1970s, such that there are few traditionalists left anywhere in colleges of education.

A common thread among these studies is an intellectual history of what is called critical pedagogy, a phrase derived from Paulo Freire, the influential Brazilian educational theorist. Schools of education have moved from being guided by progressivism in the 1920s, to multiculturalism in the 1970s and 1980s, to critical pedagogy today. On the surface, Freire’s book, The Pedagogy of the Oppressed, criticizes the ordinary lecture-and-response-classroom, where a “paternalistic” and authoritarian teacher “deposits” conventional knowledge into passive students. Freire had much more in mind than criticizing lectures as an educational technique, however. He regarded any method that tries to fit students into and get them to prosper within the existing social order as a prop of capitalism and white supremacy. He thought the purpose of education was raising the revolutionary consciousness of students, especially in elementary education. As Peter McLaren writes, “The purpose of dialectical educational theory [i.e., critical pedagogy], then, is to provide students with a model that permits them to examine the underlying political, social, and economic foundations of the larger white supremacist capitalist society.”

Critical pedagogues perceive modern America to be a dark place where the economy favors the few and where the society as a whole is inherently racist, sexist, and homophobic. Traditional schools are, in the words of the critical pedagogue and Freire student, Henry Giroux, “breeding grounds for commercialism, racism, social intolerance, sexism and homophobia.” Without critical pedagogy, this breeding ground forms the “hidden curriculum” in schools. With critical pedagogy, schools can become fonts of liberation, resistance, and disruption. Yet Freire’s critical pedagogy was not a practical program to achieve specific educational goals. He set the goals. Other scholars, underlaborers in the critical pedagogy project, invented the more technical academic theories to reduce his goals to practice. Gloria Ladson-Billings and Peggy McIntosh are, like Giroux, prominent disciples of Freire. Such underlaborers authored key concepts like cultural competence, culturally responsive or relevant teaching, white privilege, queer theory, comprehensive sexuality education, decolonizing the curriculum, and restorative justice that reduce critical pedagogy to practice. Ladson-Billings, one of the most assigned authors in UF’s elementary education program, introduced “culturally responsive” teaching, which uses the students’ own standards and norms as the basis for classroom rules. McIntosh, also prominently featured in UF’s elementary education major, coined the term “white privilege.” UF has renamed this critical pedagogy as “equity pedagogy”, a distinction without a difference.

The following study goes deep instead of wide. It searches the courses students must take to graduate from UF’s COE with the elementary education major and identifies those with critical pedagogy and its derivative concepts. We have collected the most recent, publicly available syllabi from required courses in the elementary major. This study draws conclusions about courses from course descriptions, course learning outcomes, required readings and assignments, and course materials assigned to students in their Canvas accounts outside of public view. Using the data, we rank courses as red when critical pedagogy is sown into the entire framework of the course, yellow when courses mix professional standards with critical pedagogy, and green for those that portray adherence to strict professional standards. This methodology is conservative, since professors who embrace critical pedagogy (and there are many in UF’s COE) could bend a relatively professional-looking syllabus toward critical pedagogy without the public becoming aware. We omit consideration of courses outside the school of education, like general education.

This is an opportune time to conduct such a study in Florida. While Florida provides many routes to certify teachers, the most usual route to certification is still through degree programs from approved schools of education. What happens in those required and recommended courses helps make teachers what they are. This is especially true for elementary education majors. Recognizing this, Florida’s process for certifying teachers is enshrined in laws and regulations and then executed in schools of education at universities and colleges. These laws mostly lay dormant since politicians and regulators are understandably reluctant to oversee the syllabi of university curriculum and to comb through contested policies, practices and curricula that run afoul of the state’s values. Still, Florida policymakers have recently adjusted criteria for certifying teachers through laws and regulations. By 2021, schools of education had adopted an untested and ineffective whole language, “three-cueing” model for teaching reading. Florida lawmakers and regulators required schools of education to abandon whole-language approaches and offer the science of reading, phonics-based reading programs (Reg 6A-5.066). This is a model for regulation.

In 2024, Florida’s legislature, understanding how critical pedagogy had come to grip schools of education, passed House Bill 1291 to regulate teacher preparation programs. The state will not certify programs that, according to HB 1291, “distort significant historical events or include curriculum or instruction that teaches identity politics” or are “based on theories that systemic racism, sexism, oppression, and privilege are inherent in institutions of the United States and were created to maintain social, political, or economic inequities.” Certified programs “must afford candidates the opportunity to think critically, achieve mastery of academic program content, learn instructional strategies, and demonstrate competence.” This “don’t-do-that-but-instead-do-this” approach is now going to guide regulations for teacher certification again. UF’s COE and all other colleges of education around the state should look inward to their own practices as regulators imagine a new and better future for Florida’s schools of education.

As this report shows, the beating heart of the elementary education major at UF violates HB 1291. After relaying our general findings and providing the receipts, we make recommendations for how Florida might continue efforts to reform K–12 education through emphasizing classical education and professional methods as well as regulating its state-funded schools of education.

The Curricular Revolution of 2020: UF Overhauls the Elementary Education Major

UF’s College of Education revolutionized its elementary education curriculum after the Summer of Floyd in 2020. This revolution consisted of removing courses that emphasized professional standards and practical advice for prospective teachers, while adding courses infused with critical pedagogy.

UF’s faculty used declining enrollments as a pretext to create an elementary education major focused on critical pedagogy. It trimmed the number of courses so as to attract new students. What emerged was not a leaner major, however. Four “equity pedagogy” classes were added in the curricular revolution. Existing courses changed markedly. The COE’s proposal to the University’s Curriculum Committee (UCC) shows that political diagnoses, not professional considerations, motivated the change. “The state of our nation and global society,” according to the proposal, “leads us to conclude that emphasizing a social justice focus in our new program is important and much needed.” The COE’s advocate told the UCC that “the proposed changes . . . focus on diversity and equity.”

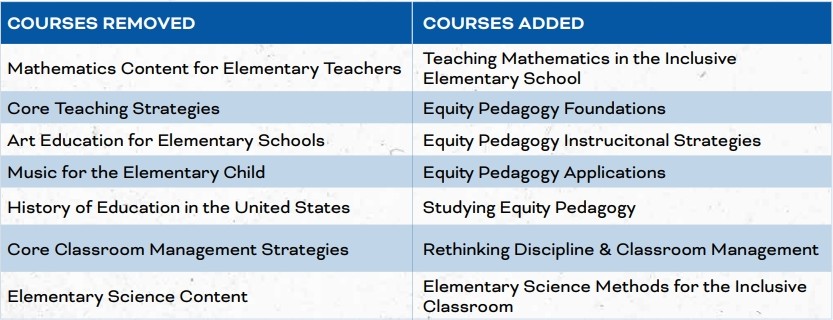

Courses infused with social justice ideology replace practical courses like Mathematics Content for Elementary Teachers, Art Education for Elementary Schools, and Music for the Elementary Child would no longer be required. Math and science would be reconfigured to emphasize social justice and equity issues as well. (See Table A for the courses dropped and added in UF’s curricular revolution.)

Table A: The Curricular Revolution of 2020: Removed and Added Courses

Curricular changes allowed the College of Education to “continue advancing issues of anti-racism, diversity, equity and inclusion.”

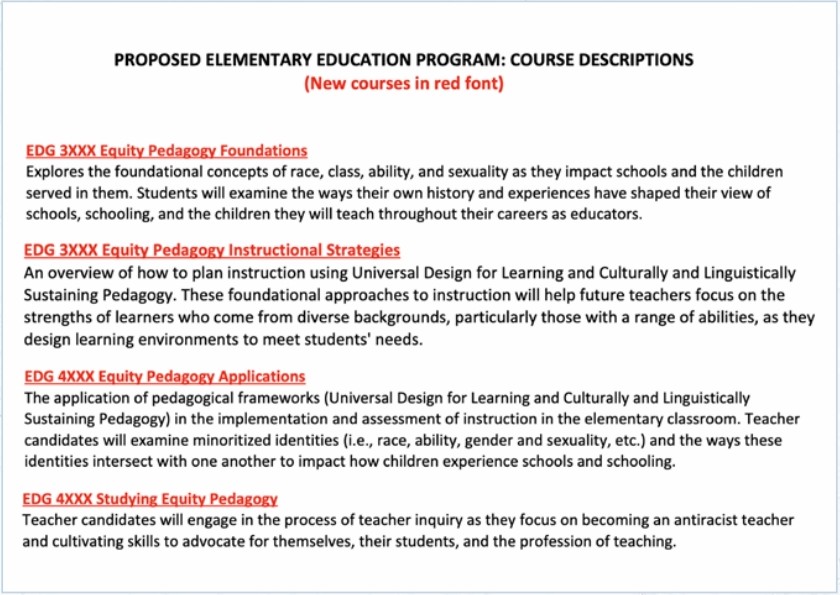

The course Core Teaching Strategies was eliminated. It was effectively replaced with a four-course sequence in equity or critical pedagogy. Knowledge and character are not foundational in UF’s COE. Rather, the first of the required courses focuses on “the foundational concepts of race, class, ability and sexuality as they impact schools.” Students will “define educational equity and state historical reasons for the inequalities that exist in public schools today” and learn to “articulate beliefs they hold about instruction that can prove problematic to the educational achievement of children from minoritized groups.” (This report catalogs many such assertions in these four equity pedagogy courses in Section 4 and in Appendix A).

A mandatory course titled Core Classroom Management was replaced by a mandatory class called Rethinking Discipline and Classroom Management. The new course is part of an effort to build culturally-responsive classrooms and also to raise the consciousness of teachers. Unlike the old course, which emphasized the nuts and bolts of organizing classrooms, the new course is about rethinking discipline and management. It deconstructs “classroom management as it currently exists in schools, developing the skills to work within this system while simultaneously challenging and disrupting common practices that have adversely affected many school children including Black and Brown students . . . LGBTQ students.” Its readings focus on restorative justice programs—a lenient approach to discipline, which research has found decreases achievement and increases rates of misbehavior and violence—and equity-based Multi-Tiered Systems of Support for minoritized bodies. New classroom management is more about allowing students to follow their own standards of good behavior and preventing teachers from imposing their ways onto the unique minority cultures that abound in our multicultural present.

The old math class, where teachers learned elementary math content, was replaced with Elementary Mathematics Lab. This new class is “inquiry-based”–another classroom approach that mountains of research has deemed ineffective – and involves hands-on activities related to foundational concepts in elementary mathematics, with an emphasis on family/community experiences [and] equity and social justice issues.” The move away from the “sage on the stage” style and the embrace of the “guide on the side” style–so common to critical pedagogy–is evident in most of these courses.

These curricular changes allowed the COE, in the words of Dean Glenn Good, to “continue advancing issues of anti-racism, diversity, equity and inclusion.” Nor did the revolution stop at course catalogs. The College enacted additional policies and programs such as conducting a search for an Associate Dean for Faculty Affairs, Diversity, Equity, Inclusion and Community Engagement and establishing a “Collective for Black Student Advancement to identify action items to enact positive change.” College-level hiring has reflected the new need to provide equity pedagogy for relevant majors. Most EdDs in the COE have been written to reflect the research interests of faculty promoting equity pedagogy—and UF is thus preparing the next generation of activist college educators that will prepare future K–12 teachers (though this is a story for another report).

The Revolution of 2020 will continue rolling into the future, unless the department changes direction or is forced to through intelligent regulation.

Highlights from UF’s COE curricular proposal

General Findings

The beating heart of UF’s elementary education major violates Florida law.

The beating heart of UF’s elementary education major violates Florida law. Let the plain facts about the program be submitted to a candid world.

UF’s elementary education major is centered on equity pedagogy. Equity pedagogy is a form of critical pedagogy—a patently radical philosophy of education that prioritizes “raising the consciousness” of students so they can transform society instead of emphasizing formal academic training. Critical pedagogy and its derivative concepts aim to identify and eradicate disparate outcomes among groups through manipulating standards and practices and to kindle the revolutionary consciousness among teachers and students. Teachers are presumed to be agents of a systemically racist (or homophobic, etc.) system. Critical, equity pedagogy seeks to deconstruct the teacher’s cultural identity so that he or she can teach in an environment where students from different cultural backgrounds are treated according to the standards of their unique background. In reality, it replaces traditional cultural, academic and behavioral norms with a more radical ethic of resistance, disruption, agitation, and opposition. In fact, this report finds that:

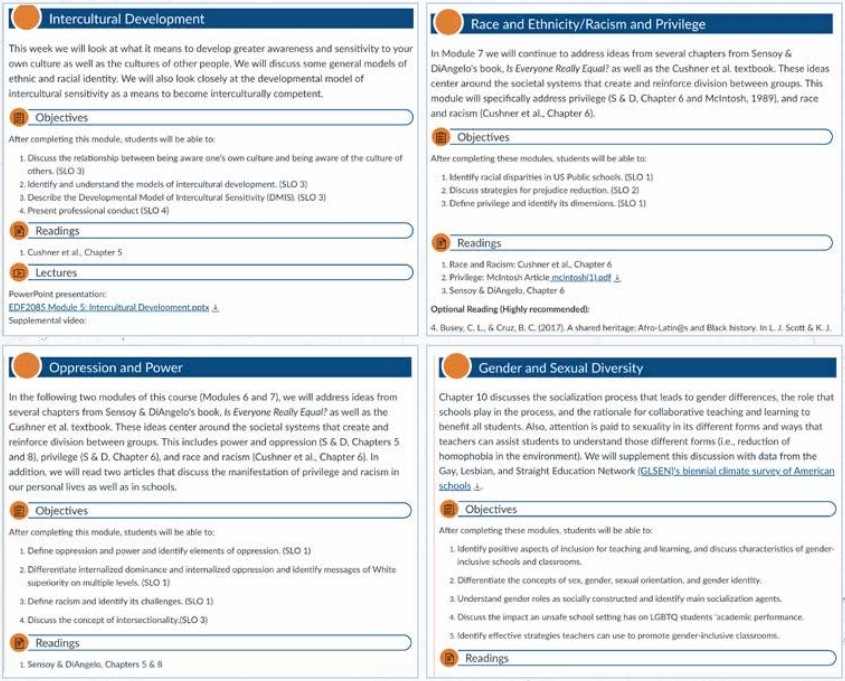

- Two of the four “critical tracking” or prerequisite courses for all education majors use equity pedagogy as the framework for the course (EDF 1005: Introduction to Education and EDF 2085: Teaching Diverse Populations).

- All four “equity pedagogy” courses are required of elementary education majors—one required each semester of junior and senior year—are infused with critical pedagogy.

- The approach to classroom management as seen in EDG 4442: Rethinking Discipline and Classroom Management is derived from the restorative justice movement, recommending that whites and blacks, as well as other minorities be held to different standards for discipline in the classroom and that single standards are marks of white privilege.

- Several of the subject matter specific courses like MAE 4310: Teaching Mathematics in the Inclusive Elementary School and SSE 4312: Social Studies for Diverse Learners are either infused with critical pedagogy or mix critical pedagogy with some professional standards in their syllabi.

- More technical courses involving the teaching of reading, teaching labs, student teaching, or the integration of technology into the classroom manifest less critical pedagogy in their syllabus. (Movements to replace the Western approach to the scientific method with indigenous approaches are afoot, for instance, and equity pedagogues are on the front lines in putting them forward.)

While not every course in UF’s elementary education major is steeped in critical theories, the radical, one-sided nature of these courses must be seen to be believed. All material in Appendix A comes from course syllabi and assignments verbatim.

Table B presents an overview of the required and recommended courses in UF’s elementary education major.

Table B: Equity Pedagogy in UF’s Elementary Education Major

The teaching practices and educational philosophy surrounding “equity pedagogy” violate Florida’s HB 1291 (2024). Teacher preparation programs, according to the law, “may not distort significant historical events or include curriculum or instruction that teaches identity politics . . . or is based on theories that systemic racism, sexism, oppression, and privilege are inherent in institutions of the United States and were created to maintain social, political, or economic inequities.” Equity pedagogy, as it is defined in theory and in practice within UF’s elementary education major, is based on the theory that America and Western civilization as such are built upon a systemically racist foundation that can only be overcome through transformative teaching. It therefore violates the spirit and the letter of HB 1291.

This bold statement requires systemic proof. Systemic proof arrives as a series of propositions:

- UF’s elementary education major embodies an overriding commitment to equity pedagogy, not just a good-faith investigation of it as one valid option among many (as revealed in the required books, the course descriptions, and course learning outcomes).

- Equity pedagogy embodies theories traceable to critical pedagogy and to practices like culturally responsive teaching, restorative justice, radical gender ideology, action civics, multiculturalism, transformative social and emotional learning, and others.

- Such theories reflect the idea that America is systemically racist, sexist, or just plain oppressive—one central to all critical pedagogy.

- UF’s elementary education program is populated with people who are products of institutions dedicated to an understanding of education inseparable from these multiplying number of educational theories.

UF’s elementary education major violates HB 1291. Therefore, the College must either change or be prevented from certifying teachers.

Let us prove proposition 1. Course descriptions demonstrate the moral center of UF’s elementary education major. As the syllabus to EDG 3623 Equity Pedagogy Foundations begins, the program is centered on equity pedagogy. The course catalog quotes EDG 3623 almost verbatim. “The program is intentionally designed to develop teacher candidates’ competence in working with current school systems while simultaneously cultivating the knowledge, skills, and dispositions necessary to challenge existing systems that fail to support the learning needs of all children.”

The four-course sequence in equity pedagogy presents itself as a remedy to America’s systemic racism. The first course, EDG 3623 Equity Pedagogy Foundations, is about “Situating Self and Others in Schools, Community, and Society: Teacher as Cultural Beings.” According to the course description, the school system is now denying racial and sexual minorities an equal chance for a sound education, but the elementary education program will prepare to help students “to change the system” so that it does. The course description reads, in the relevant part:

University of Florida’s Elementary Education program prepares the next generation ofteachers to address this cultural gap and become leaders in the creation of more equitable and socially-just classroom experiences for all children. This program is intentionally designed to develop your competence in working within the current school system while simultaneously cultivating the attitudes, skills, and dispositions necessary to change the system to address the learning needs of all children regardless of race, class, gender, sexuality, ability, language, and other differences.

The course readings—surveyed in Appendix A—support just such a view of the world, as they include only books told from the perspective of critical race theory or radical gender theory. Nearly every reading in the course—both the required readings and suggested ones—arise from within the worldview of critical theory. Students even take an implicit bias test as part of being evaluated. Other assignments in the program are infused with racialist assumptions of critical pedagogy.

The other three equity pedagogy courses build on EDG 3623. As fruits of this tree, they cannot but partake in its character. The second course, EDG 3343: Equity Pedagogy Instructional Strategies, has as its theme “Situating Self and Centering Others in Instructional Design: Teacher as Instructional Designer.” The third course is EDG 4703: Equity Pedagogy Applications. It addresses the question, “How do I enact pedagogy that is accessible to all learners?” while the fourth course, EDG 4048: Studying Equity Pedagogy, brings the why, what, and how together in a continuous process of evolution toward unique professional practice as a teacher. As readings, assignments, and course objectives make clear, each course emphasizes political activism and creating agents of social change. Teachers are to “become leaders in the creation of a more equitable and socially-just classroom”; to see “equity as essential to the process of teaching and learning”; and “construct lesson plans that are culturally and linguistically sustaining.”

Other courses revolve around this moral center as well. Restorative justice ideology shapes the approach to student discipline and classroom management. EDG 4442: Rethinking School Discipline and Classroom Management suggests that “the growing cultural gap between communities and schools” should inform how teachers discipline—different standards for different subcultures. Only if teachers are “cultivating the attitudes, skills, and dispositions necessary to change the system” can students truly learn to be “disrupting common practices that have adversely affected many school children, including Black and Brown students…” MAE 4310: Mathematics Content & Methods for Teaching Mathematics in Inclusive Elementary Classrooms emphasizes “culturally and linguistically responsive” teaching, where students “adjust story problems to be more culturally relevant,” though there are attempts to teach mathematics in the course as well. SDS 3430: Family and Community Involvement in Education contains only one required book out in the open, a book about “building culturally responsive family-school relationships” and assignments asking how to “create a culturally responsive teaching plan for students” from a particular family. RED 3211 Teaching Language and Meaning Construction in Elementary Reading embodies the “critical reader response approach” to teaching language. There are three general approaches to literary theory: a formalist or traditionalist approach (what does this book say?); a reader response approach (What do you think about this book? How does it make you feel?); a “critical” approach (What does this book, as an artifact, tell us about the oppressive structures of Victorian England? Let’s read Romeo and Juliet through an antiracist or feminist lens). This course is based on the critical approach. SSE 4312: Social Studies for Diverse Learners is also infused with the culturally relevant teaching model.

On proposition 2, a close reading of the assigned writings and assignments (as cataloged in Appendix A) also shows that most readings employ methods derived from critical pedagogy, including culturally responsive teaching, restorative justice, radical gender ideology, action civics, and transformative social and emotional learning. Many other scholars of educational theory have shown these practical applications of Freire’s critical pedagogy are “based on theories that systemic racism, sexism, oppression, and privilege are inherent in institutions of the United States.” This is a plain violation of HB 1291.

Also, with respect to proposition 4, the professors in UF’s COE are also professionally committed to these ideological modes of teaching, as a review of their social media posts and curriculum vita would surely demonstrate. Many aspects of UF’s elementary education major violate HB 1291 as it is written. Other degree programs probably have the same problems. Therefore, the College must either change or be prevented from certifying teachers.

Prospects for Reform

Schools of education have given prominence to multicultural education approaches for more than forty years. Before that, progressive educators did a lot to wipe out classical approaches to educating the educators. It is difficult to recover the older, classical way of teaching in generations where the modern progressive and multicultural modes have been embraced. Florida, however, has stated the intent and taken no few actions to recover classical education. This act of recovery, after decades of neglect, requires ending the Left’s project in schools and replacing it with classical education. Florida has sought to do this first through eliminating DEI programs and also through the adoption of new higher standards called the Florida Benchmarks for Excellent Student Thinking (B.E.S.T.) standards in English Language Arts, Civic Literacy, Mathematics, Social Studies, and more.

What would a recovery of classical education in public schools look like? First, as Florida’s new standards emphasize, the great purpose of education is transmission, not social transformation. Awareness of and appreciation for our civilizational heritage drives classical education. It is not “child-centered” nor does it aim to fit students into contemporary society; rather, classical education is civilization-centered. For instance, before progressive reforms, classical educators put the history and myths of Western civilization at the heart of childhood education, emphasizing the heroes of our cultures (like Alfred the Great or Alexander the Great) and Greek, Roman, and even Norse myths as a way of firing up the imagination of young people. Even early progressive schools did not neglect such heroes. Under multicultural education, there are no civilizational heroes; there are instead supposedly unsung heroes who have overcome the oppression of our civilization. Today, few students even know George Washington had wooden teeth! Similarly, under classical education, great inventors and scientists could be celebrated. Today, our historic inventors are often as unknown as their methods, as many critical educators teach and even celebrate supposedly indigenous methods. Cultural literacy has been replaced with racial literacy and equity pedagogy.

Imagine if instead of four courses on equity pedagogy, teachers were required to take four courses on the content informing Florida’s B.E.S.T. standards and the great political, artistic, and religious events of our civilization; if they knew the names of the great symphonies and works of art; if they could put together a timeline of one hundred pivotal events in the history of Western civilization; if they could recite portions of great epic poems. Contemporary education has none of this. Florida’s COE has too little of this. But it could happen either through the COE’s voluntary compliance with HB 1291 or through the more difficult task of regulation.

For example, history pedagogy has already moved from the cultural literacy that emphasizes building a foundation of knowledge of important dates, persons, events, and ideas to one that scorns what it deems to be mere memorization and that focuses instead on identifying hidden biases and other supposed processes of reasoning. And that emphasis is seen in UF’s social studies courses for the elementary education major. Instead, the course titled Social Studies for Diverse Learners seeks to “create supportive, accepting, student-centered classroom environments,” recommends that students subscribe to a journal called Rethinking Schools, and assigns A Different Mirror for Young People: A History of Multicultural America, all of which are explicitly anticlassical and move toward adopting a critical historical approach to American history. The course is infused with culturally responsive pedagogy. It does not have to be that way. UF’s COE could willingly put Florida’s B.E.S.T. State Academic Standards at the heart of its social studies courses.

As Florida implements HB 1291, it should broadly displace education theories traceable to the ideas of critical pedagogues with elements traceable to classical education and professional teaching methods as found in the new Florida standards. Policymakers should use the “don’t-do-that-but-instead-do-this” formulations that guided schools of education to displace whole language learning with a phonics-based “science of reading.” The ideas animating such critical pedagogy can be more slippery, and COE professors are bound to hide their radical commitment to critical pedagogy. Achieving the goals of HB 1291 demands careful crafting and determined regulation with real penalties for violations. At stake, ultimately, is whether particular schools of education will remain able to certify teachers.

Any rule change should imagine how to displace the equity pedagogy model in UF’s education majors with a more salutary, classical approach. Among our suggestions for rule changes are the following:

- Strategies should not emphasize eliminating gaps in student achievement as the result of race, sex, ethnic identity, or disability, but rather should aim to increase the knowledge and subject matter mastery of every individual student in the classroom.

- Evidence-based strategies derived from the federally developed practice guides housed within the “What Works Clearinghouse” and in the Florida Department of Education rather than abstract theories traceable to critical pedagogy should guide schools of education in their constructions of syllabi and class material.

- Strategies appropriate for the teaching of history and social studies should not elevate historical reasoning above cultural literacy of facts, events, ideas, and persons that helped build America as a self-governing country or that made Western civilization powerful.

- Strategies aimed at teaching the fundamentals of Western science and its methods and at instilling a sense wonder in students at the glories of nature must be privileged over indigenous methods of scientific inquiry.

- Strategies derived from critical race theory, culturally responsive pedagogy, restorative justice, transformative social and emotional learning, and other derivatives of critical pedagogy must not form the basis for organizing required classes; instead, required classes must emphasize cultural literacy, comprehensive history of education and its related philosophies, content instruction, cognitive theories of learning, classroom management, and the delivery of content derived from Florida’s state standards.

- The department of education will use periodic discretionary review authority to ensure that assignments do not involve overmuch personal reflection as opposed to content-based reflection or that curriculum does not emphasize consciousness raising and having proper beliefs rather than core teaching methods.

Schools of education that cannot deliver on grounding education practices in traditional learning as opposed to critical pedagogy must lose their ability to certify teachers.

Conclusion

UF’s COE has lost its way. Its new elementary education curriculum is infused with divisive, ideological concepts derived from the revolutionary ideas of critical pedagogy. If UF’s COE does not change it will run up against the standards embodied in HB 1291 and the coming regulations. Other elements of the COE are also, it is safe to infer, as infused with critical pedagogy as the elementary education major. New teachers are not prepared for classroom management; rather, their consciousness of their own privilege is raised and they are encouraged to be skeptical about the behavioral standards of traditional American society. They are not steeped in core teaching strategies; instead, their consciousness regarding their own biases is supposedly raised. The COE elementary education does not emphasize core content knowledge, but revolutionary ideology.

Yet it is not beyond hope that UF could once again find its way. UF should voluntarily eschew the divisive, ineffective, highly partisan approach to teacher preparation that now guides its elementary education major. Reversions to the pre-2020 curriculum, while not sufficient, would be a good place to start. So, too, would a formal effort to integrate Florida’s new B.E.S.T standards into teacher preparation as much as possible. Thus, UF’s COE could provide a model for reforming its teacher preparation programs from which other states can follow. At the same time, Florida can maintain alternative modes of teacher certification. As school choice becomes more deeply embedded in Florida’s education practice, schools themselves could continue to certify or decide on teacher qualifications.

Either way, the survival of schools of education as vehicles of teacher preparation cannot be taken for granted. Enrollments are dipping. Alternative modes of certification are there. The best survival strategy is to offer genuine value to students and school districts and the state as a whole. Genuine value will come from complying with HB 1291, not from following the lemmings in other schools of education over the cliffs.

Appendix A: Highlights from the Relevant Elementary Education Course Material

Several reports have provided a detailed analysis of the various writings informing modern critical education. I encourage everyone to read them. What follows is a set of highlights from the required courses in UF’s elementary education major. Elements that point unmistakably to critical pedagogy are highlighted in bold and italics. Heretofore, this report has relied on providing the big picture of what is taking place in UF’s elementary education major. This is where we provide many of the most important receipts.

One important element of critical pedagogy, however, should be noted beforehand, since it reveals much about the overall structure of UF’s elementary education major. Critical pedagogy emphasizes personal stories, self-reflection, and other subjective techniques of evaluation over knowledge of facts or theories. Critical pedagogues tend to be generalists armed with abstract theories about how society works. They are concerned first and most centrally with race, as Gloria Ladson-Billings and her coauthor wrote in a 1995 article titled “Toward a Critical Race Theory of Education,” “Race first!” In this way, the emphasis on self-reflection in assignments, the lack of emphasis on strategies and techniques for teaching, and the obsession with race are part of this entire approach to education.

RED COURSES: Required or Recommended Courses Infused with Equity Pedagogy

EDG 3623 Equity Pedagogy Foundations

From Course Overview: Today’s schools are often characterized by incredible racial, ethnic, social class, linguistic and cultural diversity. However, school curricula, instructional strategies, and teacher demographics rarely reflect this diversity and represent a growing cultural gap between communities and schools. University of Florida’s Elementary Education program prepares the next generation of teachers to address this cultural gap and become leaders in the creation of more equitable and socially-just classroom experiences for all children. This program is intentionally designed to develop your competence in working within the current school system while simultaneously cultivating the attitudes, skills, and dispositions necessary to change the system to address the learning needs of all children regardless of race, class, gender, sexuality, ability, language, and other differences. To prepare you to become a teacher who can help all learners thrive in and outside of school, the program is centered on equity pedagogy. Teacher candidates who complete coursework in equity pedagogy will be prepared to leverage the assets of students and families from diverse backgrounds to engage in meaningful change in the classroom, community, and beyond. . . .

This course, the first in the four-part course series, is taken during your first semester in the program. The theme of this semester is “Situating Self and Others in Schools, Community, and Society: Teacher as Cultural Being.” As the first course in the equity pedagogy series, this class will address this theme by introducing you to concepts (such as race, class, ability, sexuality) that are necessary to explore in order to understand the ways your own prior history and experiences have shaped the ways you see yourself, schools and schooling, and the children you will teach throughout your career. In particular, in this first class we will focus primarily on race. This class addresses the question, “WHY” equity pedagogy?

From Course Objectives:

Upon successful completion of this course, students will be able to:

- Define educational equity and state historical reasons for the inequalities that exist in public schools today

- Articulate beliefs they hold about instruction that can prove problematic to the educational achievement of children from minoritized groups.

- Assess and examine their own biases and the role they play in understanding issues of equity within schools and the larger society.

- Identify larger societal issues related to inequity and its impact on individuals as reflected by narratives in young adult literature.

- Identify characteristics of racism and the impacts it has on teaching and learning in the classroom.

Selections from Required Readings:

Alexander, M. (2012). The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness. New York: New Press.

Bolgatz, J. (2005). Talking Race in the Classroom. New York: Teachers College Press (Chapter 2).

Dixson, A. D., & , C. Rousseau Anderson (2017). “The First Day of School: A CRT Story.” In Critical Race Theory in Education: All God’s Children Got a Song, edited by A. D. Dixson, C. Rousseau Anderson, and J. K. Donner, 57–64. New York: Routledge.

Evans, E. (2017). “White Girl Teaching.” International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education31 (2): 158–61.

Howard, T. C. (2003). “Culturally Relevant Pedagogy: Ingredients for Critical Teacher Reflection.” Theory into Practice 42 (3): 195–202.

Kailin, J. (2002). Antiracist Education from Theory to Practice. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.(Chapter 5).

McIntosh, P. (1989). “White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack.” Peace and FreedomMagazine, 10–12.

Michael, A. (2015). Raising Race Questions: Whiteness and Inquiry in Education. New York: Teachers College Press. (Chapter 2)

Mott-Smith, J. A. (2008). “Exploring Racial Identity through Writing. In Everyday Antiracism: Getting Real about Race in School, edited by M. Pollock, 146–53. New York: New Press. (Chapter 27)

Moradi, B. (2017). “(Re)focusing Intersectionality: From Social Identities back to Systems of Oppression and Privilege.” In Handbook of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity in Counseling and Psychotherapy, edited by K. A. DeBord, A. R. Fischer, K. J. Bieschke, and R. M. Perez, 105–27. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Sealey Ruiz, Y. (2011). “Dismantling the School-to-Prison Pipeline through Racial Literacy Development in Teacher Education.” Journal of Curriculum and Pedagogy 8 (2): 116–20. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15505170.2011.624892.

Silva Parker, C., & Willsea, J. (2011). “Summary of Stages of Racial Identity Development.” Interaction Institute for Social Change, 1–5.

Smith, I. E. (2016). “Minority vs. Minoritized.” The Odyssey Online. September 2, 2016. https://www.theodysseyonline.com/minority-vs-minoritize

Stevenson, H. (2015). “Hearing the Lion’s Story: Racial Stress Can Silence Children; Storytelling Can Awaken Their Voices. Learning for Justice. Spring 2015. https://www.learningforjustice.org/magazine/spring-2015/hearing-the-lions-story.

EDG 3343: Equity Pedagogy Instructional Strategies

From Course Description:

Today’s schools are often characterized by incredible racial, ethnic, social class, linguistic and cultural diversity. However, school curricula, instructional strategies, and teacher demographics rarely reflect this diversity and represent a growing cultural gap between communities and schools. University of Florida’s Elementary Education prepares the next generation of teachers to address this cultural gap and become leaders in the creation of more equitable and socially-just classroom experiences for all children. This program is intentionally designed to develop your competence in working within the current school system while simultaneously cultivating the attitudes, skills, and dispositions necessary to change the system to address the learning needs of all children regardless of race, class, gender, sexuality, ability, language, and other differences. To prepare you to become a teacher who can help all learners thrive in and outside of school, the program is centered on equity pedagogy. Teacher candidates who complete coursework in equity pedagogy will be prepared to leverage the assets of students and families from diverse backgrounds to engage in meaningful change in the classroom, community, and beyond.

From Required Textbooks:

- Heumann, J. & K. Joiner. (2021). Rolling Warrior: The Incredible, Sometimes Awkward, True Story of a Rebel Girl on Wheels Who Helped Spark a Revolution. Boston: Beacon Press.

- Ladson-Billings, G. (2009). The Dreamkeepers: Successful Teachers of African American children. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Meyer, A., D. H. Rose, & D. T. Gordon (2014). Universal Design for Learning: Theory and Practice. Wakefield, MA: CAST Professional.

EDG 4703: Equity Pedagogy Applications

From Course Description:

This course, Equity Pedagogy Applications, builds upon the why of equity pedagogy from your Equity Pedagogy Foundations course, the what of equity pedagogy from your Equity Pedagogy Instructional Strategies course by addressing the question, “How do I enact pedagogy that is accessible to all learners?” Students will learn how to design and implement effective instruction to meet the needs of all learners and begin a cycle of inquiry to improve their pedagogical practice(s). This course is housed in the College of Education School of Teaching & Learning.

From Course Goals:

By the end of the course, the successful student will be able to:

(1) Describe how Culturally and Linguistically Sustaining Pedagogy and Universal Design forLearning pedagogical frameworks converge to enable teachers to address the learning needs of all children;

(2) Address barriers in schooling to support all students;

(3) Construct lesson.

From Required Texts:

Gino, A. (2022). Melissa (Previously Published as George). Scholastic.

Hammond, Z. (2015). Culturally Responsive Teaching & the Brain: Promoting Authentic Engagement and Rigor among Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Students. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

Muhammad, G. (2020). Cultivating Genius: An Equity Framework for Culturally and Historically Responsive Literacy. Scholastic.

Nelson, L. L. (2021). Design and Deliver: Planning and Teaching Using Universal Design for Learning (2nd ed.). Baltimore: Brookes.

EDG 4048: Studying Equity Pedagogy

From Course Overview:

In addition, during this “putting it all together” class, we will focus explicitly on equity pedagogy grounded in an inquiry stance, as well as cultivating skills to advocate for your students, yourself, and the profession of teaching. In this course we will answer the questions: What does it mean to study your own practice as a teacher committed to the creation of more equitable schools and classrooms? How do I study my own professional practice to achieve a more equitable and socially-just classroom? What role do leadership and advocacy play in the profession of teaching?

From Course Objectives:

- Select, summarize, and synthesize literature to inform a question of practice formulatedabout implementing equity pedagogy in their internship classroom

- Complete one full cycle of inquiry related to a question of practice formulated aboutimplementing equity pedagogy in their internship classroom

- Share their inquiry learnings with others at the Inquiry Showcase to engage in collegial conversations focused on equity pedagogy and inquiry

- Articulate and represent their vision for their enactment of equity pedagogy in their future work as teachers

Critical Tracking or Prerequisite Course

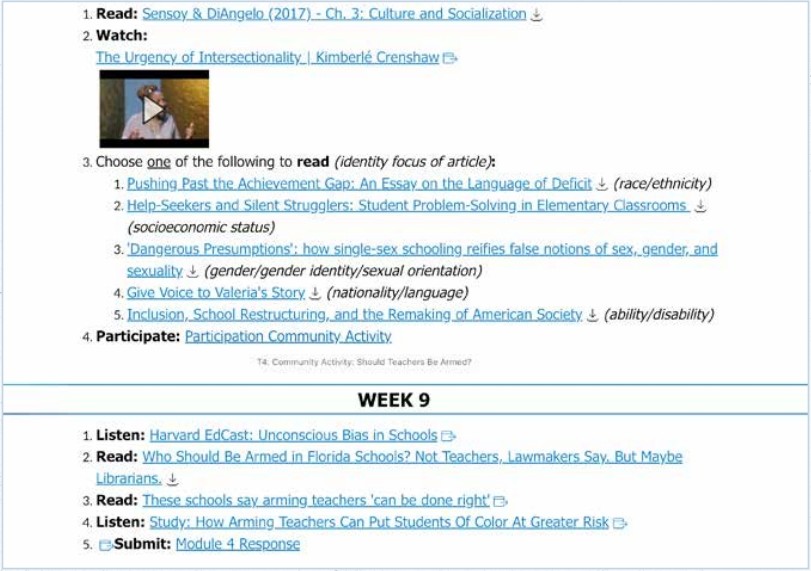

EDF 1005: Introduction to Education

From Course Description:

You will (1) examine educational foundations through contemporary events, phenomena, and trends; (2) explore the realities of educational spaces and those who occupy them; and (3) reflect on your evolving perspectives about the education profession.

Selections From Required Readings:

Crenshaw, Kimberle. “The Urgency of Intersectionality” (video).

Jackson, Janna. “‘Dangerous Presumptions’: How Single-Sex Schooling Reifies False Notions of Sex, Gender, and Sexuality” in Gender and Education (2009).

Sensoy, Ozlem, and Robin DiAngelo. “Prejudice and Discrimination.” In Is Everyone Really Equal?: An Introduction to Key Concepts in Social Justice Education, chapter 3.

From Course Assignments:

None of the assignments concern rigorous work. All of them are “reflection” papers on course modules, the entire course, or field experience.

Below is an example of coursework assigned to students in Canvas:

EDF 2085: Teaching Diverse Populations

From Course Description:

A survey of educational demographics, foundations of prejudice, elements of culture, political and philosophical roots of diversity and commonality, and barriers to cultural understanding and diversity in the classroom.

Designed for the prospective educator, this course provides the opportunity to explore issues of diversity, including an understanding of the influence of disabilities, culture, family, gender, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status, religion, language of origin, ethnicity, and age upon the educational experience. Students will explore personal attitudes toward diversity.

From Student Learning Outcomes:

By the end of this course, students will:

• Describe factors contributing to student diversity and inequalities in education associated with ability, gender, language, race, and social class.

• Identify the elements of inclusive classrooms and schools that accommodate and respond to the diverse learning needs of all students.

• Increase awareness of cultural identity and factors that contribute to intercultural understanding.

Selections from Required Texts and Additional Readings:

Cushner, K., McClelland, A., & Safford, P. (2022). Human Diversity in Education: An Intercultural Approach (10th ed.).

Dweck, Carol S. “Mindsets and Human Nature: Promoting Change in the Middle East, the Schoolyard, the Racial Divide, and Willpower.” American Psychologist (2012).

GLSEN. The 2017 National School Climate Survey: The Experiences of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer Youth in our Nation’s Schools.

McIntosh, Peggy. “White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack.”Sensoy, Ozlem, and Robin DiAngelo. Is Everyone Really Equal?: An Introduction to Key Concepts in Social Justice Education (2nd ed.).

From Assignments: None of the assignments require rigorous work.

Cultural Autobiography: The cultural autobiography is designed to encourage students to critically think about their cultural identity within a continuum of roles and categories within society.

Ethnography Project: Students will work in groups to complete a semester-long project focused on engaging in an in-depth learning experience about a cultural group to which you do not belong.

Below is a sample of coursework assigned to students in Canvas:

Subfield Specialty Courses

EDE 3941 Critical Rotations Across Diverse Elementary School Contexts

From Course Description:

A Teacher’s pursuit of DEI activism is a lifelong endeavor. These clinical rotations are an essential step in the lifelong journey towards becoming an effective and inclusive educator and offer the opportunity to examine various questions within dynamic classroom environments. Students are required to compare all experiential learning in elementary classrooms in relation to what they learn in their classes about equity pedagogy. By the end of your junior year, you will have explored three different elementary education school contexts and compared, contrasted, and analyzed each experience in relation to what you are learning in EDG 3623: Equity Pedagogy Foundations (fall semester), EDG 3343: Equity Pedagogy Instructional Strategies (spring semester), as well as additional courses are taken concurrently with this field-based experience course.

From Course Objectives:

Questions addressed in the course focus heavily on personal experience, “positionality” aka levels of privilege, and reflections on one’s personal history.

1. How does my evolving understanding of my prior history, experiences, and current positionality continue to shape how I see myself, schools and schooling, and the children I will teach throughout my career? . . .

4. What does it mean to be a professional and establish professional relationships with fellow educators, administrators, students, and families in diverse community settings?

From Instructional Materials/Assignments:

In this class, you are expected to connect to readings and text assignments associated with EDG 3623: Equity Pedagogy Foundations (fall semester) and EDG 3343: Equity Pedagogy Instructional Strategies (spring semester) within your core assignments.

● Students are required to keep a reflection journal. “Becoming a Reflective Practitioner” These Journaling exercises focuses on self-consciously examining one’s beliefs and practices as opposed to “mindlessly implementing systems designed by others.” “We believe that reflective professionals (those who self-consciously examine their beliefs and practices) are much more effective than technicians (those who mindlessly implement systems designed by others). . . .

● Everything must be connected to instruction in the Equity Pedagogy course

These prompts serve to connect what you have learned and will be learning in your equity pedagogy courses and other coursework to your experiences in the field.

EDG 4442: Rethinking School Discipline and Classroom Management

From Course Description:

As you have learned during your first year in this program, today’s schools are often characterized by incredible racial, ethnic, social class, linguistic, and cultural diversity. However, school curricula, instructional strategies, and teacher demographics rarely reflect this diversity and represent a growing cultural gap between communities and schools. Your program prepares you to address this cultural gap and become a leader in creating more equitable and socially-just classroom experiences for all children. As such, your program is intentionally designed to develop your competence in working within the current school system while simultaneously cultivating the attitudes, skills, and dispositions necessary to change the system to address the learning needs of all children regardless of race, class, gender, sexuality, ability, language, and other differences.

New teachers report that one of the most challenging aspects of learning to teach and their first years of teaching in the current school system is understanding and working with the behavior of the students they teach. Hence, in this course, you will explore classroom management as it currently exists in schools, developing the skills to work within this system while simultaneously challenging and disrupting common practices that have adversely affected many school children, including Black and Brown students, students whose first language is not English, immigrant students, students with ability differences, LGBTQ students, and students who live in poverty.

We will accomplish this goal through the consideration of several questions, including

● What do teachers need to know about student behavior?

● What are some ways that behavior is currently understood in schools?

● What happens when teachers’ understanding of classroom management is clearly linked to issues of justice, equity, inclusion, and diversity?

● How do teachers create classroom learning environments that are culturally responsive and conducive to the learning of all students?

From Course Objectives:

Upon successful completion of this course, students will be able to:

● Describe and problematize the relationship between schools and behavior.

● Compare Restorative Practices to other forms of classroom management.

From Required Textbooks:

Shalaby, C. (2017). Troublemakers: Lessons in Freedom from Young Children at School. New York: New Press.

Smith, D., Fisher, D., & Frey, N. (2015). Better Than Carrots or Sticks: Restorative Practices for Positive Classroom Management. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

McCart, A., & Miller, D. (2020). Leading Equity-Based MTSS for All Students

MAE 4310 Teaching Mathematics in the Inclusive School

From Student Learning Outcomes:

5. Students will be able to plan lessons that integrate the use of technology to support the learning of culturally and linguistically diverse students.

6. Students will be able to plan for language sensitive mathematics content instruction for emergent bilinguals . . .

7. Students will be able to plan differentiated learning experiences for emergent bilinguals and integrate their cultural background knowledge, learning styles, and prior formal educational experiences.

From Assignments: (All points in course are related to equity pedagogy)

CASE STUDY (35 POINTS TOTAL)

This assignment focuses on student learning, identity, and dispositions of a K–2nd or 3rd–6th grade emergent bilingual student. In working with this student, you will consider how to use their knowledge, linguistic abilities, and cultural background in mathematics instruction. You will first conduct a “Getting to Know You” interview, where you learn about your case study student’ interests, math background, and cultural background. You will then adjust story problems and your anticipated questioning from the “Problem Solving Interview” protocol to be more culturally responsive to your child. You will then conduct a “Problem Solving Interview” with that same student. After conducting the “Problem Solving Interview,” we will participate in a mock caregiver/teacher conference to practice communicating achievement expectations and student progress to parents.

Part 1: Mathematics “Getting to Know You” & Developing Culturally Relevant Tasks Written Report (10 points)

You will ask questions to become more familiar with the student’s activities and interests, the student’s home, community knowledge base, and resources. You will also adjust story problems to be more culturally relevant to your student.

Part 2: Problem Solving Interview & Written Report (K–2nd Grade Interview & 3rd–6th Grade Interview) (20 points)

Problem Solving Interview You will conduct a problem-solving assessment with your case study student. This interview provides an opportunity to practice eliciting, interpreting, and assessing students’ thinking about mathematics, with a particular focus on children’s understanding of whole number and fraction concepts.

CULTURALLY RESPONSIVE FUTURE TEACHING PROJECT (20 POINTS)

The Culturally Responsive Future Teaching Project is your opportunity to curate resources and ideas that resonate with you pertaining to issues of Access and what culturally responsive mathematics will look, sound, and feel in your future classroom. Throughout the course of the semester, you might encounter these through our discussions, readings, videos, or even in your work at your school site. This guide will remind you how to establish instruction that is culturally relevant and meaningful in your future classroom and adjust instruction to meet the needs of your ELLs. You can write a 3–5 page . . . describing your current thinking about how the teaching and learning of culturally responsive mathematics will be implemented in your future classroom. This will also include rich descriptions of the types of activities with technology integration that will take place, the interactions that will occur, and your overall philosophy/beliefs about the teaching and learning of culturally responsive mathematics. Provide support from readings and class activities to support your most current thinking about the teaching and learning of culturally responsive mathematics.

Yellow Courses: Critical Pedagogy Mixed with Professional Standards

SDS 3430: Family and Community Involvement in Education

From Required Readings:

Amatea, E. (Ed.) (2012) Building culturally responsive family-school relationships.

From Assignments:

Family Diversity Small Group Project

During the semester you will be organized into small groups and asked to form a family of your own based on a case study assigned to your group. Please plan to get organized and get underway with this project as soon as teams are announced! (I suggest you exchange contact information with your group members)The purpose of this assignment is threefold:

● To explore the influences of family diversity on professional teaching practices and interactions with families.

● To increase your understanding of the particular strengths and obstacles faced by families in differing life circumstances.

● To develop instructional strategies that connect all types of one family’s funds of knowledge, including ELL’s, gifted and ESE, to your classroom instructional goals and practices

The steps in the assignment are to:

1. Read your case study and create a genogram/relationship map outlining the relationships in the family and involved school professionals.

2. Respond to the discussion questions proposed in your case as a group *group questionsmassignment

3. Develop a presentation, together as a group, in which you outline the composition of your family, identify their funds of knowledge, explain any special challenges, present your family’s situation, and provide suggestions for how one might create a culturally responsive teaching plan for students from this family.

SSE 4312: Social Studies for Diverse Learners

From Course Description:

As part of this course, students will engage with multicultural social studies content and with a variety of approaches to social studies planning, instruction, and assessment. Pre-service teacher candidates will also grapple with teaching complex and controversial social issues to young learners. . . .

From Course Goals:

5. Examine social studies content standards for limitations and opportunities to explore multicultural approaches to social studies education at the elementary level. . . .

8. Utilize a variety of frameworks to conceptualize a democratic approach to elementary social studies content. . . .

11. Create authentic assessments for social studies that have value beyond school, involve disciplined inquiry, and facilitate the construction of knowledge.

12. Discuss approaches and beliefs towards addressing current events and controversial issues in the elementary social studies classroom.

From Course Texts:

Takaki, R. (2012). A Different Mirror for Young people: A History of Multicultural America. Boston: Back Bay Books.

From Assignment Descriptions:

Cooperative Children’s Book

The purpose of this assignment is to develop an integrated social studies/language arts project through the creation of a children’s biography. In small groups, you will write original children’s biographies. You will take a person, event, or concept from Ronald Takaki’s book (grades 4–5) and turn it into an age-appropriate children’s book to be read or used in a social studies class for elementary school. You will also incorporate one of the five themes of geography and learn to consider geography beyond mapping activities. The project will generally follow the procedures outlined in Parker.

TSL 3520: ESOL Foundations: Language and Culture in Elementary Classrooms

From Course Description:

This course will examine issues of language and culture that are relevant for elementary school learners of English as a second language (ESL). The course has three main sections: (1) the role and nature of culture and its influence on learning for diverse English learners (ELs); (2) an introduction to the structure of language and to principles of first and second language development in young learners; and (3) ESOL Policies & Practices in Schools & Communities. Readings, vignettes, film documentaries, case studies, audio, video, and language samples are used for reflection, analysis, and in-class discussion activities.

X

X

Facebook

Facebook

Truth Social

Truth Social