Abortion as a Proxy Battle Over the Sexual Revolution

This essay was originally published in Public Square Magazine on November 8, 2022.

In the ongoing debate about religion, politics, and abortion, far less attention has gone to how the desire to do whatever people want sexually shapes the entire conversation.

Summary: Religious people are less likely to support abortion—but not because religions directly teach that abortion is wrong. Rather, abortion is connected to the sexual “liberation” ethic that arose during the sexual revolution of the 1960s. Traditionalist believers reject abortion because they reject sexual promiscuity. Conversely, acceptance of the sexual revolution drives support for abortion inasmuch as abortion, along with reliable contraception, renders sexual promiscuity “safe.” Conservatives must recognize that pro-life arguments will have limited effectiveness if they avoid addressing the central issue: the desirability of the sexual revolution.

Many Americans see abortion as a religious issue. One can buy shirts that read: “Keep your religion out of my uterus” or “keep your rosaries off my ovaries.” Joshua Greene argues that opposition to abortion requires a belief that fetuses have “souls,” which he considers to be an unprovable theological dogma. Mona Eltahawy even described the pro-life movement as “a white supremacist Christian movement driven by white supremacist, Christian zealots who are patriarchal to the core.” On this view, pro-lifers believe life begins at conception because God told them so.

If so, it follows, as many secular Americans argue, that abortion restrictions constitute an (unconstitutional) attempt to impose one’s religious views on the country. Progressives routinely liken the post-Roe world to the theocratic state depicted in the novel The Handmaid’s Tale, where a patriarchal ruling class uses women as breeding machines.

Pro-lifers vigorously deny the charge that abortion restrictions amount to establishing a state church. Unjustified abortion, they say, is equivalent to murder, which everyone agrees is wrong. As Tim Carney points out: “The Fifth Commandment, that ‘thou shalt not kill,’ is part of religion, right there in the Bible. Yet somehow, murder statutes do not amount to ‘theocracy.’” Many pro-lifers take pains to produce non-religious arguments—from biology, medicine, philosophy, and ethics—to defend the status of fetuses as living persons.

Rationalist arguments will fail to persuade people’s minds if their bodies demand access to abortion.

The question of religion in the abortion debate is thus a sensitive one. Yet even for pro-life Christians, the alignment between Christian teaching and anti-abortion arguments does not imply that the latter depends exclusively on the former—despite insistence to the contrary.

So, who is right? Is abortion primarily just a religious issue?

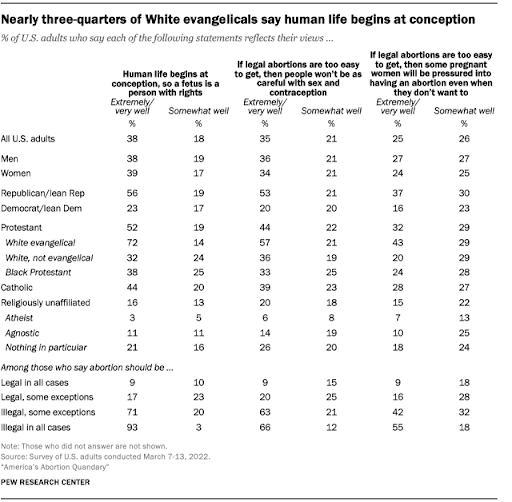

Views on Abortion are Correlated with Religiosity

Clearly, there is a religious divide over abortion in America. If you’re not religious, you’re simply more likely to be okay with abortion—with people of faith largely being opposed. Pew Research summarizes the statistics as follows: “An overwhelming share of religiously unaffiliated adults (83%) say abortion should be legal in all or most cases, as do six in ten Catholics. Protestants are divided in their views: 48% say it should be legal in all or most cases, while 50% say it should be illegal in all or most cases. Majorities of Black Protestants (71%) and White non-evangelical Protestants (61%) take the position that abortion should be legal in all or most cases, while about three-quarters of White evangelicals (73%) say it should be illegal in all (20%) or most cases (53%).” 56% of U.S. Muslims endorsed the right to abortion in all or most cases, versus 42% opposed. (Separate polling shows that 70% of Latter-day Saints believe that abortion should be illegal in all or most cases, compared to 27% who thought it should be legal in all or most cases.)

Similar gaps exist regarding the moral status of the fetus:

Religiosity thus correlates positively with opposition to abortion. The same survey reports that Catholics who attend mass regularly are more likely to oppose abortion than other Catholics. Moreover, religious groups have led the fight against abortion. Tim Carney observed that the “March for Life is technically a secular event. But everywhere you look, religion is there.” A common sign reads: “Pray to end abortion.” No wonder many people consider abortion largely a religious issue.

Theology Cannot Explain Why Religious People Oppose Abortion

While religion clearly impacts opinions on abortion, abortion is not a religious issue for the reason most people assume. On a theological level, the Bible never explicitly mentions abortion and does not definitively claim that life begins at conception. This is not to deny that different solid biblical cases can be made against abortion. In addition to the prohibitions against murder, for instance, people could hint at many references to God’s involvement in creation: “For you formed my inward parts; you knitted me together in my mother’s womb. … My frame was not hidden from you, when I was being made in secret, intricately woven in the depths of the earth” (Psalm 139:13-15). Or hints at a pre-birth identity, where God tells the prophet Jeremiah: “Before I formed you in the womb I knew you, before you were born I set you apart; I appointed you as a prophet to the nations.” The Apostle Paul also claims that God “set me apart before I was born.”

The problem is that this evidence is not definitive. The Psalms are poems filled with metaphor and non-literal imagery. And perhaps Jeremiah’s calling was based on God’s foreknowledge of what he would become when he grew up.

Mosaic law in Exodus 21:22-25 also does not settle the issue. This passage concerns a situation in which men are fighting and “hit a pregnant woman, so that her children come out.” If “no mischief follow,” then the offender is punished “as the judges determine,” but “if any mischief follow,” then he must be executed. Conservatives interpret this passage to mean that if the child is born alive (though prematurely), the man receives a lesser penalty than if the child miscarries and dies. However, others interpret the phrase “her children come out” as “she has a miscarriage,” implying the death of the child, and think the “mischief” refers to the death of the woman, not the baby. On this view, the passage implies that the fetus is less valuable than a person because only the death of the mother, and not the fetus, triggers the (death) penalty for murder.

Furthermore, opinions on abortion in the Abrahamic religions have varied over time. Orthodox Judaism permits abortion in some circumstances and does not consider the fetus to have the same status as a born person. Christians have tended historically to be opposed to abortion, but there is some nuance. Believers have disagreed over whether there were “formed” and “unformed” fetuses, with the latter being less human. Some Christians believed that “ensoulment” happens only at “quickening”—i.e., the moment when the mother first feels the baby move—although most theologians held that abortion was wrong at any stage of pregnancy. Islamic legal scholars are all over the place, and most Muslim countries permit abortion to varying degrees.

Thus we can see that theology alone does not explain why abortion is a “religious issue.” The biblical evidence is too weak to bind people who want to accept abortion. And even if the Bible spoke more plainly, fidelity to scripture is obviously waning even among the faithful. Recently, many evangelicals who claim to accept biblical authority have rejected the longstanding Christian consensus against premarital sex and gay sex. There is no reason to believe abortion is any different.

Abortion is Related to the Sexual Revolution

My thesis is that the abortion-religion correlation can be best explained by reasons that are not related to abortion directly—but rather reflect one’s views on sexuality. Pregnancy results from sex, after all, and abortion terminates a pregnancy. Abortion is thus implicated in the conflict over the sexual revolution. Let me explain.

The contours of the modern debate over abortion have historically been clear. The English common law did not consider abortion prior to “quickening” to be homicide. During the nineteenth century, however, scientific advances led to an abandonment of untenable positions regarding fetal development. As it became scientifically clear that “quickening” did not represent a distinct phase in the fetus’s development, doctors increasingly spearheaded opposition to abortion. In 1869, the Catholic Church eliminated its longstanding distinction between an “animated” and “unanimated” fetus and began applying the same penalty (excommunication) to all abortions at any stage. States began passing restrictions on abortion at any stage in the 1820s, a process that accelerated after the Civil War and was complete by 1900.

This status quo of heightened restrictions lasted until the sexual revolution of the 1960s. Since that time, many of the main proponents of abortion in the twentieth century have simultaneously advocated “liberation” from traditional sexual ethics. True, the connection between abortion rights and casual sex is rarely mentioned aloud. Abortion is hidden behind vague terms such as “reproductive health care,” “control of one’s body,” or “bodily autonomy and self-determination.” But the fact remains that unwanted pregnancies are an obstacle to free sex. Since many people do not use contraception correctly or consistently, abortion is needed to block the allegedly “life-destroying” pregnancies that predictably result. This is why, in the wake of the Dobbs decision overturning Roe v. Wade, many women proclaimed the “end of hookup culture,” warning men that they will stop having random sex with almost-strangers. Many women freely admit that they got an abortion so that they could continue having casual sex.

Feminists sometimes say that abortion has something to do with “equality” or “nondiscrimination” for women. At first blush, this claim is bizarre. Men cannot have the “right” to get an abortion because they cannot become pregnant, so giving the right to abortion to women does not correct discrimination or asymmetrical legal privileges. Moreover, abortion proponents universally hold that only the mother can decide whether to abort the fetus. This means it’s a man—more than a woman—who is more likely to become a parent unwillingly. Women can avoid motherhood by opting for abortion, but to avoid fatherhood, a man must resort to hectoring his pregnant lover to get an abortion—as many sadly do.

Some feminists have spoken of the problems with “forced fatherhood” and conceded that no man should be forced to assume parental responsibility for his offspring unwillingly. But the idea of either parent being allowed to demand an abortion is clearly untenable. Among other things, fathers in these situations end up grappling with the psychological pain of knowing that one’s child is “out there.” Thus, far from correcting a pro-male bias, an abortion right introduces a new legal inequality that favors women.

The “inequality” abortion claims to rectify is not legal but sexual. Men can have sex without getting pregnant, whereas fertile women cannot. A sexually active fertile woman exposes herself to greater risks than a sexually active man. If she gets pregnant and abortion isn’t available, at a minimum, she faces months of discomfort followed by a painful birth that will alter her body permanently. Even if she gives up the baby for adoption or the father is made to contribute equally to the child’s upbringing, she has suffered far more tangible consequences for the sexual act than he has. The “equality” feminists arguably seek, then, is the equal ability of men and women to have sex without consequences.

Comparing the various religious sects further supports the hypothesis that opposition to abortion derives from sexual ethics and not religious dogma. Virtually every sect that adopts a permissive view of premarital sex also endorses abortion. Virtually every sect that adopts a restrictive view of premarital sex also opposes abortion. The conservative Southern Baptist Convention, for instance, opposes premarital sex and abortion, while the Presbyterian Church (USA) accepts both. If the Bible is the sole cause of opposition to abortion, then we would expect all Christians to oppose it.

It is the defense of sexual liberation that distinguishes modern defenders of abortion from their earlier counterparts. Even when some abortions were legal and theologians debated the difference between “formed,” and “unformed” fetuses, Christians, Jews, and Muslims all rejected the idea that abortion should be a means of sexual liberation or used to cover up promiscuous sex. Kristin Luker observes that early Christian “church councils … outlined penalties only for those women who committed abortion after a sexual crime such as adultery or prostitution,” although most Christians still held that abortion was always wrong. In Islam, a woman must have a legitimate reason to obtain an abortion. Color me skeptical that medieval Muslim clerics regarded the need to “find oneself” as legitimate. And Orthodox Judaism has generally disallowed abortion for “trivial” reasons, including economic insecurity, allowing it primarily when the life of the mother is endangered.

The Sexual Revolution Distorts Rational Deliberation about Abortion

The connection between abortion and sexual license makes the job of the pro-life movement harder. Certainly, some liberationists can be convinced to oppose abortion through philosophical arguments about the origin of life. Fetal ultrasounds also appear to change some minds on abortion and cause a small number of women seeking abortion to carry the baby to term, an effect that is larger in ultrasounds of more developed fetuses.

But, since humans are not perfectly rational, there are limits to philosophical argumentation. Jonathan Haidt asserts that moral beliefs are based on intuitions and that it is often only after adopting a deeper conviction that one constructs a “rational” justification to present in public (Haidt 2012, chap. 2). Moreover, one’s self-interest affects one’s moral opinions, as numerous philosophers attest. Alexis de Tocqueville recalls meeting a French immigrant who, in France, had been a “great leveler and ardent demagogue,” but in America, having become a wealthy landowner, now spoke eloquently about the value of “property rights” and social “hierarchy” (Democracy in America, 329-330). Tocqueville “marveled” at “the imbecility of human reason” in light of “the power that material well-being exerts over political actions and even opinions” (329-330). James Madison concurs: “As long as the connection subsists between [a person’s] reason and his self-love, his opinions and his passions will have a reciprocal influence on each other; and the former will be objects to which the latter will attach themselves” (The Federalist, #10). David Hume even referred to reason as the “slave” of the “passions” (A Treatise of Human Nature, p. 415). In short, humans tend to believe whatever we want to believe.

As an adherent of the tradition of natural law, I am reluctant to accept this verdict fully. Yet one’s material self-interest undoubtedly affects one’s opinions on disputed moral topics. Even the foremost natural law thinker, Thomas Aquinas, held that while “general principles” of the natural law cannot “be blotted out from the hearts of men,” a person’s “reason may be hindered from applying the general principle to a specific act by lust or some other passion” (Political Writings, p. 125). It is no surprise that the only passion Thomas mentions by name is “lust,” since elsewhere he writes that the “vehemence of this passion is more difficult to overcome” than that of any other “sensual pleasure.” Unfortunately, this happens to be the very passion boosting support for abortion.

If support for abortion is predicated on a visceral, fleshy desire for sexual “liberation,” then rational arguments against abortion face severe limits. We should expect to encounter enormous resistance from people whose personal lives are shaped by the easy availability of casual sex. Simply put, if people have to choose between giving up promiscuous sex or believing that a fetus is merely another body part, most will choose the latter.

The Progressive Backlash against the Sexual Revolution is Ineffectual

If my analysis is correct, it follows that the pro-life cause will not fully triumph until a shift away from sexual license has occurred.

There is some good news on this front. Feminists increasingly realize that the modern sexual ethic is not working—especially for women. Consider two recent books: The Case Against the Sexual Revolution, by Louise Perry; and Rethinking Sex: A Provocation, by the progressive Catholic convert Christine Emba. Both authors praise marriage, criticize hook-up culture, accept some innate sex differences, and think that sex is “special.” If more widespread resistance to sexual liberation is to be found anywhere, here are some positive percolations.

But Perry and Emba are pushing against powerful tides. As Mark Regnerus argues in his book Cheap Sex, the introduction of hormonal contraception in the 1960s, and abortion in the 1970s, transformed the structure of the marriage market by weakening the link between sex and reproduction, thereby introducing the possibility of “cheap sex” or “free love.” On the “sexual economics” theory described by Regnerus, women control access to sex (because they desire it less and are therefore more willing to walk away), but men control access to a monogamous relationship (because they desire it less). Men give commitment in order to get sex until love transforms the relationship into a true mutual partnership. Prior to the 1960s, when the “cost” of sex was high because the risk of pregnancy rendered sex dangerous for the woman, men had to make a substantive commitment to obtain sex. Now that sex is less risky, men can obtain it for as little as the price of a few drinks.

Only a wholesale change in sexual ethics can create a society in which abortion is no longer seen as necessary for personal fulfillment.

The cheapening of sex, Regnerus concludes, enhances men’s power in the dating market. Women find themselves feeling more and more powerless to “hold out” and demand commitment from men in exchange for sex. They often feel used and devalued. As one woman writes about her college pseudo-boyfriends, [“a]fter I began having sex with these guys, the power balance always tipped.” These structural factors explain why hookup culture is so resilient despite widespread disappointment with how it works. A woman who resolves to withhold sex until she gets commitment very likely ends up with neither.

This analysis highlights the weakness and limitations of the feminist case against the sexual revolution. Perry and Emba’s arguments are half-hearted. Neither seeks to roll back the sexual revolution entirely. They want couples to wait longer—but not until marriage. And their prescriptions are intended to be optional personal advice, not socially enforceable norms. They seek to convince men and women that it is desirable to wait longer and be more committed, not that casual sex is “wrong.”

Unsurprisingly, this new brand of “sex-negative” feminism is not an ally of the pro-life movement. Perry is pro-choice, while Emba wants to avoid “extremism” on either side—which probably means she favors allowing abortion until the point at which most women will have already gotten one. They cannot bring themselves to roll back women’s ability to fully control their fertility. Yet by my analysis, this very right is the driving force sustaining the regime of casual sex they seek to displace.

For this reason, very likely the feminist backlash against casual sex will amount to lecturing men about the need to respect women’s desire for emotional intimacy, to little effect. A cultural shift towards waiting longer might make a difference on the margins, but an ethic of “you do you” will not change the deeper structural dynamics of the sexual marketplace.

Only Religion Can Counteract the Sexual Revolution

We are finally prepared to explain why abortion is a religious issue. Arguably, only traditional religious beliefs can sustain the old-fashioned sexual ethic that is necessary to remove the psychological barriers to rational consideration of the pro-life position. Only religions can make sexual restraint a universal normative standard rather than mere “advice.”

Why?

First, religions ground sex in a holistic, transcendent view of humans and their place in the cosmos. The Bible, for instance, opposes promiscuity and prostitution by arguing that a person’s body is a “temple of the Holy Spirit,” likens the husband-wife relationship to the relationship between Jesus Christ and the church, and opposes divorce because “God has joined [the couple] together.” When sex is viewed as an important component in an overarching divine plan for the cosmos, it is seen as sacred and meaningful.

Other worldviews lack the metaphysical resources to accomplish this hallowing of committed intimacy. Atheistic evolutionary rationalism, which I have described elsewhere, views libido as an animalistic urge governed by primal Darwinian forces. If “nature” teaches anything, it counsels men to “spread their genes” with lots of sexual partners since, after all, this behavior is common in the animal kingdom, and many human cultures have had polygamy. Evolutionary psychologists vigorously deny this implication, but only because they deny that evolution can provide any guidance at all on how we use our innate desires.

Progressivism likewise cannot see anything special about sex. It doubts the existence of a stable human nature, denies any connection between morality and nature, and considers allegedly “transcendent” values to be culturally constructed artifacts (which are probably implicated in racism, sexism, or homophobia). Moreover, progressives generally adopt a radically individualist worldview that treats one’s autonomous personal choices (especially regarding sex) as sacrosanct, eroding the ability to make long-term commitments.

Second, religions portray marital and sexual norms as divine commands, giving them a priority and clarity that is unavailable otherwise. The natural law tradition holds that, while everyone can, in principle, understand moral principles through reason alone, “divine law” or revelation is useful because it clearly and forcefully articulates important moral principles. The Anglican theologian Richard Hooker, for instance, argues that scripture “restates the natural law” in order to “prove” the “more obscure” moral principles that require complicated reasoning to discover (The Laws of Ecclesiastical Polity). Moreover, while the “first principles of the Law of Nature are easy,” determining “particular applications of this law” is trickier inasmuch as “we are inclined to flatter ourselves and to learn as little about our defects as possible.” In fact, he notes, “so far has our natural understanding been darkened that at times whole nations have been unable to recognize gross iniquity as sin.” Religious texts reinforce moral truths that are difficult for people to accept.

Sexual ethics particularly benefit from the educative function of revelation. Unlike “hard” crimes, consensual sex doesn’t appear to “harm” anyone. This may even be true in the short run. The wisdom of sexual restraint mainly becomes apparent only after the global consequences of sexual liberation have permeated and transformed society. Even then, a crude tool like abortion, in which the victim is literally hidden from sight and then tossed aside, can be used selfishly to mitigate harm to oneself and the people one knows.

The ambiguity of sexual ethics explains why, when average Americans discuss the principles by which they regulate their own sexual lives, they portray these principles as unique to themselves and nonobligatory—often accompanied by heated denials of any intent to “judge” others’ choices. Many people feel deeply that hookup culture is illegitimate because sex is somehow sacred, but they struggle to find the language to articulate this sentiment. This reticence is unsurprising. Whenever sexual ethics are framed as personal choices rather than society-level norms rooted in universal moral laws, people inevitably refrain from imposing their choices on others.

Conclusion

This argument has implications for pro-life conservatives.

First, conservatives must supplement traditional pro-life arguments with a comprehensive attack on the regime of sexual promiscuity. Fighting the battle on the sexual front is just as important as insisting on the humanity of the fetus. Rationalist arguments will fail to persuade people’s minds if their bodies demand access to abortion. On a practical level, we should not only promote traditional marriage but also seek to mitigate the temptations of hookup culture by helping young singles find a mate and get married young.

Second, conservatism must recover a recognition that personal choices regarding sex both affect and are affected by society. Perhaps the greatest failure of classical liberalism is that it cabined off entire areas of life—particularly in the sexual realm—as “private” realms shielded from moral scrutiny. We must cultivate a society where people integrate their individual choices into a holistic philosophy of human flourishing. Such an approach would constrain personal autonomy but would foster social harmony and, ultimately, individual happiness.

Finally, conservatives should temper their hopes of “winning” the debate on abortion quickly or easily. The Dobbs decision is welcome, but only a wholesale change in sexual ethics can create a society in which abortion is no longer seen as necessary for personal fulfillment. Every effort must be made to build on the work of feminist critics of casual sex. But such critiques, which largely amount to optional personal advice, stand little chance of dethroning hookup culture, which has become increasingly omnipresent in the larger culture young singles swim in. Only religion stands a real chance of checking promiscuity by inculcating a higher view of human sexuality—yet there is little evidence of a religious revival on the horizon. Debates over abortion, it seems, will remain endemic to modern liberal democracies for the foreseeable future. Buckle up.

Twitter

Twitter

Facebook

Facebook