Biden’s Eviction Moratorium Extension Is Executive Overreach

This article was originally published by Robert J. Delahunty and John Yoo at National Review on August 11, 2021.

Presidents do have broad authority to deal with emergencies. But what Biden has done exceeds any such justification.

It is rare for a president to undertake an action that the Supreme Court has just found illegal. It is rarer still for a president to do so lacking any principled constitutional grounds, and even conceding that most scholars and judges considered it to be, in fact, unconstitutional. Rarest of all is for a president to admit that his decision merely attempted to game the judicial system.

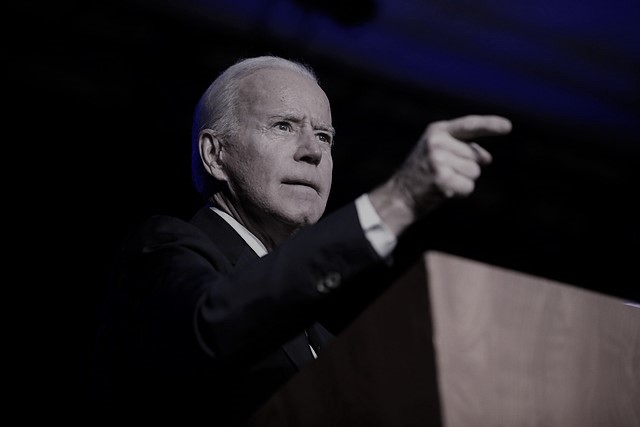

Yet that is exactly what President Joseph Biden has just done.

In extending the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s moratorium on eviction proceedings in state courts, the Biden administration has openly flouted the rulings of the Supreme Court and at least six other federal courts. It has claimed a power that the Constitution does not give the president. It has willfully misread a law as granting it power that Congress, just this year, has withheld from it. The administration’s legal position is about as sophisticated as that of Representative Maxine Waters (D., Calif.): “Who is going to stop them? Who is going to penalize them? There is no official ruling saying that they cannot extend this moratorium . . . Just do it!”

Biden’s action does not merely overreach, it subverts the idea that the executive, even during a public-health crisis, is bound by the Constitution and the rule of law. Democrats claimed, unjustly, that President Donald Trump had made dictatorial moves. They are openly and unapologetically defending such moves under Joe Biden.

We have both served as advisers to past presidents and supported broad readings of executive power to respond to emergencies. But the Biden administration’s claims of power go far beyond the constitutional text that structures our government and are unique in the history of the executive. These claims disregard the president’s fundamental duty to “take care that the laws are faithfully executed.” Last January, Biden took an oath to discharge that duty. He has violated his oath.

How did things get to this pass?

In March 2020, as part of its response to the COVID emergency, Congress imposed a temporary moratorium on evictions from rental properties that had participated in federal-assistance programs or had federally backed loans. Congress then extended the moratorium through January 31, 2021. Thereafter the CDC — acting unilaterally and without legislative authorization — extended the moratorium three times, up to July 31. The CDC’s moratorium had a far broader sweep in that it applied to all rental properties in the nation, even those that did not involve federal funds or loans.

Landlords’ groups successfully challenged the CDC’s extension of the moratorium. On June 29, Justice Kavanaugh, in a concurrence agreeing with four other justices in Alabama Association of Realtors v. HHS, wrote that the CDC “exceeded its existing statutory authority by issuing a nationwide eviction moratorium. . . . In my view, clear and specific congressional authorization (via new legislation) would be necessary for the CDC to extend the moratorium past July 31.” Despite finding the extended moratorium illegal, however, Justice Kavanaugh (the swing vote) joined another group of four justices in declining to vacate a lower court’s stay of its order enjoining the CDC from enforcing the extended moratorium. Kavanaugh allowed the CDC to carry the moratorium forward for roughly one month, until July 31, in order to give Congress the opportunity to act in that interval. On this occasion (unlike in 2020), Congress failed to act.

Lacking “clear and specific congressional authorization,” the CDC is without power to act on its own. Nonetheless, Biden gave the CDC permission to issue a new moratorium that did not differ in any legally significant way from the one that the Supreme Court majority had just found to be illegal. The CDC had argued unsuccessfully that it could regulate landlord–tenant relationships under a provision of the wartime Public Health Service Act of 1944. That provision authorized the Department of Health and Human Services to “make and enforce such regulations as in [HHS’s] judgment are necessary to prevent the introduction, transmission, or spread of communicable diseases.” In carrying out such regulations, HHS was authorized to “provide for such inspection, fumigation, disinfection, sanitation, pest extermination, destruction of animals or articles found to be so infected or contaminated as to be sources of dangerous infection to human beings, and other measures, as in [its] judgment may be necessary.” (Emphasis added.)

The Biden administration took the view that it was authorized to enter the field of landlord–tenant relations because the eviction moratorium fell under “and other measures.” This is obviously mistaken. The “and other measures” language is just a catchall for actions similar to the ones listed (“inspection, fumigation,” etc.) that Congress did not enumerate. A canon of statutory interpretation known as ejusdem generis holds that an ambiguous item in a list should be understood to have the same character as the items of a list; that is, if your spouse sends you to the grocery store for eggs, milk, a can of soup, and “anything else you need,” a reasonable interpreter does not have authority to go out and buy a Tesla.

The courts immediately recognized that Congress had not delegated anything like such unbounded authority to the CDC (even assuming Congress could constitutionally have done so, which itself is questionable). The Biden administration’s reading of the law would amount to the transfer of all of Congress’s powers to the CDC, and even more. Why wait for Congress to authorize COVID-relief funds when the CDC could just remove money from the Treasury directly? Why fight over an infrastructure bill when the CDC could just order roads and bridges to be built? Why not let the CDC decide whether to increase enforcement of immigration rules at the border and set trade rules, too? And there would be nothing to limit the CDC’s powers to the COVID outbreak: It could shut down the entire country indefinitely if it considered that action necessary to halt the spread of another communicable disease, such as seasonal flu or the measles. As the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit held in a July 23 opinion, if the CDC’s interpretation were correct, the agency would have “near-dictatorial power for the duration of the pandemic, with authority to shut down entire industries as freely as [it] could ban evictions.” The court refused to read the statute as authorizing the CDC to ‘“sweep’ constitutional traditions ‘into the fire.’”

But the Biden administration has been ready and willing to assume near-dictatorial power and to sweep constitutional traditions into the fire.

The legal logic behind the new, slightly modified August 3 CDC moratorium — if one can speak of “logic” here — is that that moratorium is more limited in scope than the prior, nationwide one. Relying (apparently) on the say-so of legal expert Laurence Tribe, the Biden administration claims that this moratorium can be defended because it applies “only” to areas where there are “substantial [or] high levels of community transmission” of coronavirus.

This story only compounds the Biden administration’s constitutional offenses. First, White House spokesman Gene Sperling had told the press only shortly before that even a moratorium targeting areas of high transmission would not survive judicial review. Second, as the Washington Post noted, the August 3 moratorium is hardly limited: It covers almost 90 percent of the country. Third, the controlling statute no more authorizes a supposedly “targeted” moratorium than it authorized a nationwide one. Could the Biden administration claim to follow the law if it censored speech in only 90 percent of the country, rather than all of it?

Rather than butchering the law, the Biden administration might have argued that evolving forms of the coronavirus have created a new national emergency, and that the president has the constitutional power to respond to that emergency even without authorization from Congress to do so. Article II of the Constitution grants the “executive power” to the president. Those who drafted and ratified the Constitution would have understood that phrase to include an ability to respond to unforeseen events, crises, emergencies, and, ultimately, war. The Founders had witnessed state revolutionary governments in which assemblies predominated and governors became dependent, resulting in instability and oppression. To cure this defect, the Federalists unified the executive power of the national government in a single president who could effectively and energetically respond to circumstances. “Good government,” Alexander Hamilton explained in Federalist No. 70, requires “Energy in the Executive,” which is “essential to the protection of the community from foreign attacks” and “the steady administration of the laws.” A single executive (rather than a cabinet or council of state) could act with “decision, activity, secrecy, and despatch,” Hamilton explained.

Whether to use such emergency power would depend on the circumstances and the nature of the threat, which almost by definition could not be fully anticipated by Congress. Indeed, the Framers created the federal government and the presidency precisely because they knew that it was impossible to define beforehand the nature of emergencies and crises, and that the better course was to create a body of government with the authority to act as circumstances arose. Because the “circumstances that endanger the safety of nations are infinite,” Hamilton warned in Federalist No. 23, “no constitutional shackles can wisely be imposed on the power to which the care of it is committed.”

For much of our history, presidents have declared national emergencies, even in the absence of legislative authority, to lead the nation in moments of crisis. Thomas Jefferson effectively did so in response to Aaron Burr’s effort to raise a rebellion in the Louisiana Territory; Abraham Lincoln declared an emergency, with far more justification, at the start of the Civil War; FDR did so, with far less justification, at the start of his presidency to handle the Great Depression; and Harry Truman did so at the start of the Korean War. In 1976, Congress enacted the National Emergency Act in its burst of post-Watergate reforms designed to restrict presidential power. While the new law terminated most existing emergencies, it did not set out any definition of a national emergency or limit the president’s ability to declare one.

Reciting the past examples of presidential energy in the face of crisis creates a sharp contrast with the Biden moratorium. When the coronavirus pandemic began, in the late winter and early spring of 2020, it presented a challenging emergency unlike anything the nation had faced in a century. President Trump declared a national emergency and issued a series of executive orders, while Congress responded with a series of measures designed to alleviate the economic suffering of the state lockdowns — including a temporary halt to evictions by property owners who received federal funding. Congress now has had ample time to deliberate over evictions, and it has chosen not to renew the moratorium. President Biden cannot claim that emergency circumstances, on a par with the Civil War or the onset of the Great Depression, currently exist that justify presidential action at odds with a Congress in full possession of its powers. (And even if Congress decided not to act, unilateral presidential action to address the “emergency” would not be the proper default position: The states have the power to shut down eviction proceedings, and some have in fact done so.)

Progressives, even more than conservatives, should be alarmed by the executive’s stepping into the breach left by congressional inaction. Consider the 1952 Steel Seizure case, decided during the Korean War. The Court held that President Truman had no independent constitutional authority — despite the threat of the cutoff of the supply of steel for armaments in a wartime emergency — to seize and operate the nation’s privately owned steel mills. Justice Robert Jackson’s concurrence in that case warned of the risks of a dictatorship on the German model if the Court acceded to the executive’s argument that the existence of a national emergency warranted Truman’s action. Although Biden’s action, which denies landlords the right to the rents from their private property, is speciously defended on statutory grounds, it is really of a piece with Truman’s. And if one accepts the Steel Seizure reasoning — as Democrats usually do, at least when they are out of the White House — then Biden’s action is as unconstitutional as Truman’s was.

But Biden is committing a worse offense against the Constitution than just claiming an emergency power that is unsuited to the moment. He is also challenging the legitimacy of a coordinate branch of government: the federal courts. It is true that this moratorium on evictions has yet to work its way up through the courts. But that should not matter — not only did the lower courts strike down almost exactly the same order already, but five justices of the Supreme Court have made clear that they believe the moratorium to be unconstitutional. Four justices — Clarence Thomas, Samuel Alito, Neil Gorsuch, and Amy Coney Barrett — dissented from the Alabama Association of Realtors case that allowed the last moratorium to survive until it expired at the end of July. Justice Kavanaugh agreed with the four dissenters on the illegality of the CDC’s extension but held off from enjoining the CDC from enforcing it because it was about to expire anyway. You could not have a clearer signal that the Supreme Court believes that an executive order violates the Constitution than for the Court to have struck it down already.

Unlike some, however, we do not believe that the Supreme Court decides all constitutional questions finally and forever. Each branch has the authority to interpret the Constitution in the course of performing its unique duties. Presidents must decide what the Constitution means when they execute the laws and exercise the veto; Congress should do the same when it considers a bill; the Supreme Court interprets the Constitution when it decides cases where a law and the Constitution conflict. President Biden is entitled to hold an interpretation of the law that is at odds with the courts. As President Andrew Jackson declared when he vetoed the bill reauthorizing the Bank of the United States: “The Congress, the Executive, and the Court must each for itself be guided by its own opinion of the Constitution.” Even though the Supreme Court had already held the bank to be constitutional in the famous case of McCulloch v. Maryland, “the opinion of the judges has no more authority over Congress than the opinion of Congress has over the judges,” Jackson averred. And, he emphasized, “on that point the President is independent of both.”

But presidents have rarely risked direct conflict with the Court, and only for the most important of reasons. Abraham Lincoln, for example, faced this challenge when he lost faith in the Court because of Dred Scott v. Sanford, which prohibited Congress from regulating slavery in the territories and held that blacks could never become citizens. Democrats accused Lincoln of inviting chaos by attacking the Supreme Court’s logic. Lincoln declared that he would obey the Court in any individual case, but, like Jackson, would not bow to the judicial opinion that justified the decision. “Nor do I deny that such decisions must be binding in any case upon the parties to a suit as to the object of that suit,” Lincoln explained in his First Inaugural Address. Decisions of the Court should receive “very high respect and consideration, in all parallel cases, by all other departments of the government.” It might even be worth following erroneous decisions at times because reversing them could entail a high cost. But “if the policy of the government upon vital questions affecting the whole people is to be irrevocably fixed by decisions of the Supreme Court,” Lincoln argued, “the people will have ceased to be their own rulers, having to that extent practically resigned their government into the hands of that eminent tribunal.”

Again, the contrast with the Biden moratorium could not be sharper. Lincoln was willing to challenge the Supreme Court but only because it had denied Congress’s power to limit the spread of the evil of slavery. He conceded that he would obey the Court’s decision in specific cases, even if he disagreed with its reasons. The question today over the eviction moratorium is simply not on a constitutional par with Dred Scott. Congress is free to enact an eviction moratorium, as it had earlier, and the states can as well, as some have. Congress has had plenty of time to consider the matter — it simply has chosen not to use its authority. For Biden to invoke a power in order to redistribute wealth among renters and property owners — an action lacking any justification remotely comparable to Lincoln’s — shows a fundamental loss of constitutional perspective. If Biden would risk the institutional legitimacy of the Supreme Court over the question of the eviction moratorium, we can expect him to give further rein to the progressives in his party who have sought to politically pressure the Court.

For all the superficial talk of President Biden’s being moderate, his disregard of the Court stands in line with the broader progressive assault on constitutional values. Progressives have demanded, among other measures, the end of the Electoral College, the override of state management of elections, statehood for Puerto Rico and the District of Columbia for purely partisan reasons, and the packing of the Supreme Court. Many Americans supported Biden because they believed his promise that he would restore stability and comity to American politics. But Biden’s willingness to run roughshod over the Court signals that Americans elected a president too weak to stand up to the more extreme elements of his party.

John Yoo is the Emanuel S. Heller Professor of Law at the University of California at Berkeley, a nonresident senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, and a visiting fellow at the Hoover Institution at Stanford University. Robert J. Delahunty is the Washington Fellow at the Claremont Institute’s Center for the American Way of Life.

Twitter

Twitter

Facebook

Facebook