The Economics of Creativity and Innovation

This book review was originally published on May 1, 2023 by Law & Liberty.

Edmund Phelps believes that exceptional growth stems from the willingness of the whole of society to innovate, take risks, and embrace uncertainty.

Nobel Prizes in economics are usually awarded to old men whose productive years are behind them. Edmund Phelps, the 2006 Nobel Laureate in the field, is an exception. With the publication of his book Mass Flourishing in 2013, Phelps proposed an entirely new way to think about economics. Periods of extraordinary economic growth, he argued, cannot be explained by monetary or fiscal policy, scientific discovery, entrepreneurship, or any of the standard categories of economic research. Instead, exceptional growth stems from the willingness of the whole of society to adopt innovation, take risks, and embrace uncertainty. I can think of no other octogenarian economist who advanced such a bold and original thesis.

Phelps continues to direct Columbia University’s Center for Capitalism and Society, although he has retired from the classroom. On the eve of his 90th birthday, he published a professional memoir, My Journeys in Economic Theory, that is courteous to his colleagues and gentlemanly toward opponents, but nonetheless documents a highly disruptive career. He began by introducing uncertainty into economists’ mechanistic understanding of inflation and employment and concluded by changing the subject of economics altogether. Students of economics will read it closely for vignettes of the most influential economists of the past half-century. They should study it for guidance on how to throw off the shackles of stale thinking.

Economics seems to continually refresh its reputation as a dismal science. Stagnant productivity and incomes remain as much of a mystery to the economics as tuberculosis was before the discovery of its bacillus in 1882. Median US hourly earnings have grown just 8% since 1979, a growth rate of 0.2% per year. This modicum of growth was eaten away by the jump in the cost of health care, which has risen to 16% of personal consumption expenditures today from 9% in 1979.

Stagnant productivity growth—what Edmund Phelps named a “structural slump” in 1994—is the cause of stagnant incomes. But the reason for low productivity growth remains a mystery to most of the economics profession.

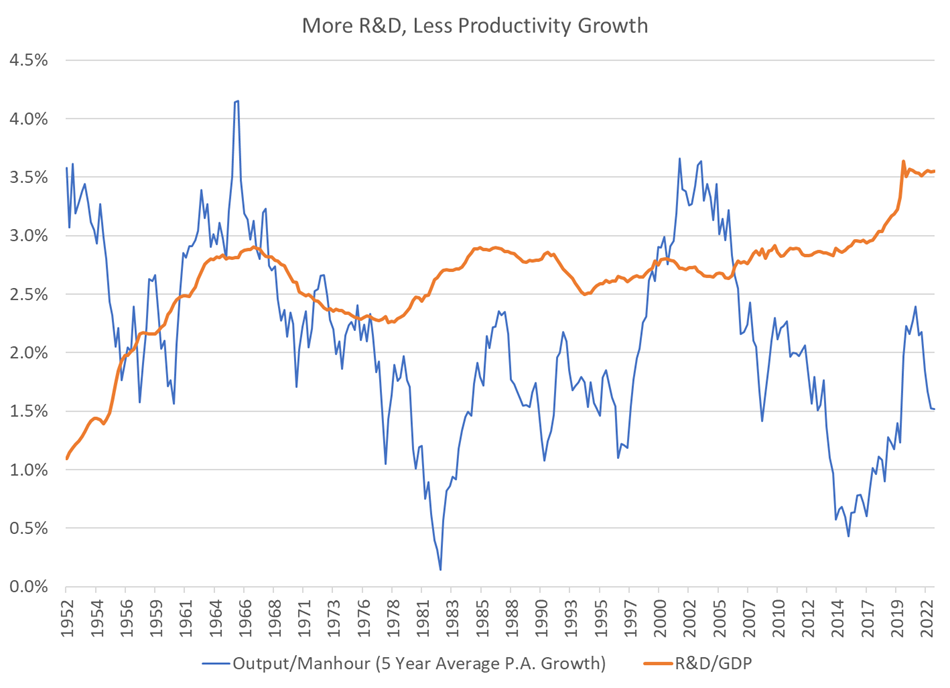

NYU Professor Paul Romer won the 2018 Nobel Prize in economics for a model that attributed productivity growth to R&D. In the classic Cobb-Douglas model of production, labor and capital inputs drive output. Romer added a turbocharger to the conventional model in which R&D investment raises the effectiveness of labor and capital. But Professor Romer’s neat mathematical formulation produces results that run counter to the experience of the past seventy years when R&D has increased as a percentage of GDP while productivity growth has fallen.

This may seem counterintuitive but consider a thought experiment: Suppose a malevolent genius spends billions on a smartphone app whose regular use deducts 50 points from the user’s IQ. That might explain why the vast sums spent on social media R&D coincide with lower productivity.

Low productivity growth is all the more worrying in contrast to the spectacular gains in productivity of the information technology sector. By the reckoning of the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the cost of computers has fallen by a factor of 25 since 1997. Yet the enormous advances in IT have had negligible impact on the broader economy.

Something clearly is amiss in the mainstream economic model. The cleverer the mathematics, the leaner the results.

The work that earned Phelps the Nobel Prize emerged from his 1966 sojourn at the London School of Economics. Phelps took on the most commonplace, insipid, and insidious fixture of economic thinking, namely the Phillips Curve, the supposed trade-off between unemployment and the wage level. The Federal Reserve remains a prisoner of the Phillips Curve, determined to increase the unemployment rate in order to lower wage rates and thereby reduce inflation.

But the Phillips Curve doesn’t work. It certainly doesn’t explain the data. During the past seventy years, changes in real wages and the unemployment rate are positively correlated, the opposite of what the theory predicts.

J. M. Keynes observed the “stickiness” of wages—the fact that wages didn’t adjust to the unemployment rate very quickly if at all—but he didn’t explain why that was the case.

Phelps introduced uncertain expectations into the equation. Inspired by the great Chicago economist Frank Knight, Phelps introduced uncertainty into the wage-price equation. Knight distinguished between “insurable risk” that could be hedged and true uncertainty, for example, an entrepreneur’s investment in a new product for which no market presently exists. The same uncertainty bedevils firms and wage earners in periods of inflation. They make guesses about the “right” level of wages, based on what they expect their competitors to pay or accept.

Therefore, “expectations of the rate at which wages are changing in the economy as a whole are of key importance for the actual rate of change of wage rates. If these expectations adjust only slowly, wage rates will tend to adjust slowly, too. As a result, the adjustment of money wages to a slump in aggregate demand will generally be slow; if the slump is mild, there may be no adjustment at all,” Phelps explains.

Phelps’ insight helps explain the behavior of inflation during the past two years, as well as the Federal Reserve’s blunders in combating it. Real hourly compensation for American workers fell almost 3% as prices jumped. Workers with “better information” switched jobs and got paid more, according to the Atlanta Federal Reserve’s wage tracker; workers who stayed in their jobs earned less. Inflation was not caused by labor market tightness, as in the Phillips Curve view, but by $6 trillion in COVID subsidies meeting production constraints across all major industries. Nonetheless, the Fed is determined to increase rates until the labor market softens. It’s the equivalent of medieval physicians bleeding a patient to reduce a fever.

More than anything else, America requires leadership that rouses our desire to create, and provides the resources to sustain it.

I do not agree with all of Phelps’ conclusions. He took issue with the celebrated argument of his late Columbia colleague Robert Mundell that if a tax cut increases economic growth, then the bonds that are issued to finance the tax cut represent an increase in wealth. The problem, argues Phelps, is that “Public debt, in adding to wealth” nonetheless “contracts investment, thus shrinking the capital stock, slowing the rise of wage rates and lifting real interest rates.” That is the likely outcome if all else remains unchanged. But if an increase in the government debt finances what Alexander Hamilton called “internal improvements,” or (as in the late 1970s and early 1980s) supports basic R&D that helps create new products, it can improve the quality of the capital stock.

Still, as Phelps writes, “It appears safe to infer that the public debt, when quite large, is a significant force dragging capital and wage rates to lower growth paths and that deficit spending is best not counted on to boost consumption or investment when the public debt is at significant heights.” When the Kemp-Roth tax bill brought the top marginal tax rate to 40% from 70% in 1981, the gross federal debt was just 30% of GDP. Today it stands at 120% of GDP, the same level as in 1945 after four years of war.

Phelps’ seminal work in wages and inflation drew on an insight into the behavior of real human beings acting under conditions of uncertainty. Classical economics treated factors of production as deterministically as gas molecules in a bottle. The real world of human uncertainty is a different place altogether. In 1966, Phelps’ work offered a small but critical correction to the prevailing determinism of macroeconomics. Mathematically elegant and technically brilliant, Phelps’ incorporation of uncertainty in the conventional model seemed more like a reform than a revolution. But it contained the seed-crystal of a transformative approach to economics that would emerge four decades later.

It was a long—but entirely logical—step from Phelps’ correction of the foundations of inflation theory to the concept of mass flourishing. Rather than put epicycles on the old Cobb-Douglas production function to explain innovation, Phelps abandoned the mathematical approach altogether and drew on fundamental insights about human behavior. “The three main elements in indigenous innovation,” he writes, “are the human capabilities at work, the desires of the nation’s people that enlist these capabilities, and the distinctive rewards of the exercise of these capabilities.” He adds, “The key premise of this new theory is that people generally possess imagination and creativity—not everyone, of course, any more than everyone is able to see or hear. … Basing a theory of economic growth, even a theory of the experience of life itself, largely on creativity was something new under the sun.”

What concerns Phelps most is what he calls “grassroots innovation,” which “came out of a desire of people, including ‘ordinary people,’ to create the new and see its use. …[This] is generated by a compound of deep-set forces: the drive to change things, a receptivity to new things and, above all, a readiness to imagine and create.” He explains:

A modern economy turns all sorts of people into “idea-men.” It is a vast Imaginarium—a space for imagining new products and methods, imaging how they might be made, imagining how they might be used. Its innovation process draws on human capabilities not utilized by a pre-modern economy. This view is radically different from Schumpeter’s 1912 thesis that innovation draws on the capacities of entrepreneurs to organize the projects made possible by outside discoveries.

If Phelps is right, we are in deep trouble. What economists call endogenous innovation arises from curiosity, love of adventure, the desire for self-fulfillment, and ambition, he argues. Yet the generation now entering the workforce is the least risk-friendly in American history. “Likely due to their risk aversion, iGen is actually less likely to want to own their own business than previous generations: only 30% of high school seniors in 2016 believed that being self-employed was desirable, down from 48% in 1987. Instead, iGen wants stable jobs in enduring industries,” argues Professor Jean Twenge of the University of California San Diego.

America used to have a spirit of adventure. The Apollo program of the 1960s and the defense-led digital revolution of the 1970s presented a surfeit of new inventions to a generation primed for great transformations. The Reagan tax cuts directed a floodtide of capital into new companies. America enjoyed the longest peacetime expansion in its history.

If there is one important element missing in Phelps’ account, it is the source of the inspiration that elicits creativity and innovation. JFK’s Moonshot and Ronald Reagan’s Strategic Defense Initiative provided a bully pulpit to summon Americans to do great things. The rousing rhetoric, moreover, was backed by substantial federal support for research and development. The federal development budget under Reagan exceeded 1% of GDP; today it is a third of a percent of GDP. More than anything else, America requires leadership that rouses our desire to create and provides the resources to sustain it.

Twitter

Twitter

Facebook

Facebook