The Fecundity of Faith

This essay was originally published by Law & Liberty on January 11, 2023.

Central planning cannot correct demographic problems, but that doesn’t mean we can’t know what the “right” demographic outcome is.

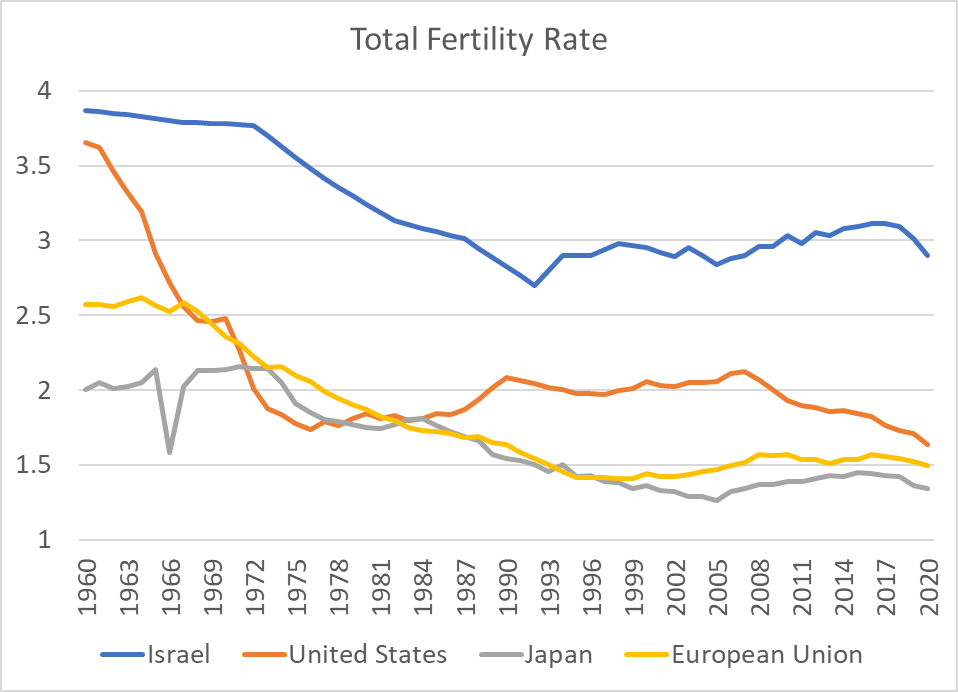

One of Lyman Stone’s central assertions in his lead forum essay on demographic decline is demonstrably wrong, and that error does fatal damage to the whole of his argument. “Fertility has fallen in the last 20 years synchronously across all the industrialized countries regardless of their cultural trends,” Stone writes. The exception that disproves the rule is Israel, with a total fertility rate of around 3 children per female. Israel surely qualifies as an “industrialized country.” Its per capita GDP in 2021 of $55,359 fell in between Austria (at $52,062) and the Netherlands (at $56,298), and higher than that of the United Kingdom, France, or Germany. Its population of 9.6 million is about equal to Hungary, Portugal, Greece, or Sweden. What possible reason does Stone have to leave Israel’s exceptional demographic profile out of the reckoning, except the inconvenient fact that it does not fit into his schema?

Israel’s overall total fertility rate is exceptional, but the total fertility rate (TFR) broken down by cohorts according to religious practice shows a pattern that is consistent with global data. A number of analysts, including Eric Kaufmann and this writer, have argued that for industrial countries that have completed the demographic transitions away from traditional society, religious practice is the strongest predictor of fertility behavior. In 2020, ultra-Orthodox Israeli Jewish women had a lifetime average of 6.64 children, “religious” women had an average of 3.92, and secular Israeli women had an average of only 1.96. Although the 1.96 figure for secular Israeli women is significantly higher than that of any other industrial country, it is nonetheless not too far from America’s 1.7. Israeli religious women have a much higher TFR than either secular women in Israel or secular women in other countries.

What we learn from the Israeli exception, in short, is that Israel is less of an exception than it seems. Israelis as a people do not have more children because they are Israelis; religious Israelis have more children because they are religious, and the deeper their religious commitment, the more children they are likely to have. What makes Israel an exception is the fact that it has a higher proportion of religious people than other countries.

Israel is the exception that proves the rule. Israel is the most religious among the high-income nations. For example, 98 percent of Jewish Israelis fix a mezuzah on their door (a small box containing hand-written Bible verses) on their door, 92 percent of male children are circumcised, and, most importantly, 70 percent maintain Jewish dietary laws at home. The dietary laws are far more ancient, and more basic to Judaism, than prayer.

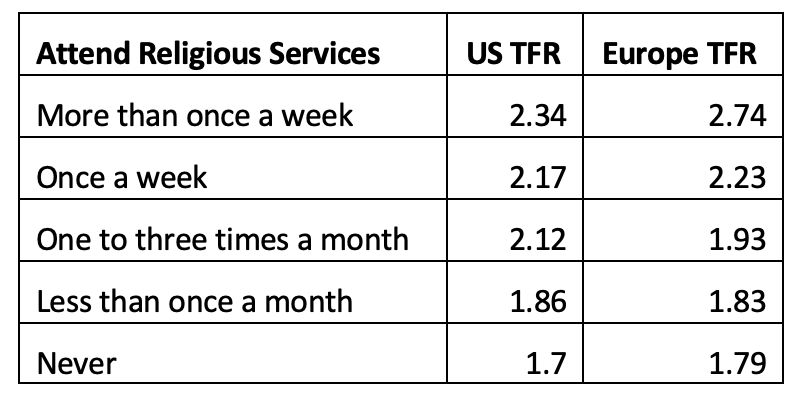

Thomas Frejka and Charles Westoff of Germany’s Max Planck Institute report the same relationship between religious practice and fertility in the United States and Europe.

I reviewed these and other data in my 2012 book How Civilizations Die. Eric Kaufmann and others have documented the same phenomenon.

A single-factor model of fertility based on religious practice is problematic, to be sure, if only because survey data struggle to capture subjective attitudes. Nonetheless, Pew Survey results for religious commitment track fertility behavior closely in the United States. The chart below was published originally in The American Mind, Jan. 10, 2022. The visual impression that the importance of religion predicts fertility behavior is supported by econometric analysis (in first differences, the importance of religion shows an adjusted r2 of 0.20 with a three-year lag against first differences in the US TFR, with a t-statistic of 2.7).

In pre-industrial societies, economic and educational variables dominate fertility behavior. Among Muslim-majority countries, by far the strongest predictor of relative total fertility rates is female literacy. The educational and economic variables cease to be important in industrial countries with highly urbanized populations. Religious faith, to be sure, is something of a placeholder for a broader set of attitudes, including hope for the future, commitment to an ethical code that sustains family life, and a commitment to the traditions of one’s antecedents that begs to be transmitted to one’s descendants. But it is the best explanatory variable we have for fertility behavior.

It is true, as Stone avers, that “stated fertility preferences are extremely strong predictors of actual fertility behaviors, stronger than covariates like religion, education, race, income, or any other socioeconomic or cultural variable.” But the fact that fertility preferences correlate closely with actual fertility behavior tells us nothing of use about either. Just what is it that determines “stated fertility preferences?” Stone points to crime and incarceration as disrupters of family life and fertility. But why should this be the case now, and not in previous generations? The total fertility rate among first-generation Irish immigrants in 1910 was 5 to 6 children, vs. 2 to 3 children for natives of native parentage. Irish immigrants were poorer than their native-born peers and more subject to the social pathologies associated with poverty, but it had no impact on their fertility behavior.

Only in the comparative short run is it true, as Kendall asserts, that “keeping transfer programs solvent requires only modest changes in taxation, and economic dynamism and mobility are influenced by demography but far more sensitive to policy choices related to education, housing, and criminal justice. It is not strictly and absolutely necessary to tackle the demographic question in order to address the problems of a lopsided age pyramid.” It is true that higher productivity (due to education) can compensate for demographic deterioration. But the numbers speak for themselves.

It is true, as Stone avers, that “stated fertility preferences are extremely strong predictors of actual fertility behaviors, stronger than covariates like religion, education, race, income, or any other socioeconomic or cultural variable.” But the fact that fertility preferences correlate closely with actual fertility behavior tells us nothing of use about either. Just what is it that determines “stated fertility preferences?” Stone points to crime and incarceration as disrupters of family life and fertility. But why should this be the case now, and not in previous generations? The total fertility rate among first-generation Irish immigrants in 1910 was 5 to 6 children, vs. 2 to 3 children for natives of native parentage. Irish immigrants were poorer than their native-born peers and more subject to the social pathologies associated with poverty, but it had no impact on their fertility behavior.

Only in the comparative short run is it true, as Kendall asserts, that “keeping transfer programs solvent requires only modest changes in taxation, and economic dynamism and mobility are influenced by demography but far more sensitive to policy choices related to education, housing, and criminal justice. It is not strictly and absolutely necessary to tackle the demographic question in order to address the problems of a lopsided age pyramid.” It is true that higher productivity (due to education) can compensate for demographic deterioration. But the numbers speak for themselves.

The United States now has 25 elderly dependents for every 100 Americans of working age. By the end of the century, it will have 50, while Italy will have 70, assuming constant fertility. That is why the Social Security system has a $100 trillion deficit at a 30-year horizon. Precisely how Stone proposes to solve this by tweaks to “housing” and “criminal justice” is a mystery.

According to Stone, “fertility has most plausibly fallen because of economic ‘failure to launch’ among young people, long delays in career stability, excessive housing costs, exploding childcare costs, rising student debts, and other adverse circumstances, not least the oppressive panopticon of social media which makes prisoners of us all.” Where is his data? US Census Bureau data shows that higher-income households have fewer children. College-educated Americans are more likely to be married, as Stone reports, but there is no evidence that this translates into higher birth rates. The precise opposite is the case.

Making people richer won’t reverse demographic decline if they apply their wealth to hedonistic indulgence rather than family formation.

Stone concludes:

We should not construe demographic decline as if we are omnipotent central planners, trying to argue about the ideal ratio of old to young, or manage the population to produce the right kinds of citizens; this is pure hubris. We don’t know the ‘right’ demographic outcome, best for human flourishing. But we can make a good guess that people know for themselves their own best outcome, and when we ask them about that in surveys, we find most people are experiencing ‘demographic decline’: seeing young people around them suffer and die excessively from drugs, alcohol, suicide, and homicide; struggling to find a suitable and stable partner while youth remains to enjoy them fully; confronting infertility due to long delays in initiation of childbearing.

In one sense, Stone is entirely correct that central planning cannot correct demographic problems (although lower taxation of families with children can help somewhat). America’s problem lies in the erosion of our religious foundation. Religious faith can foster wholesome state institutions, but the state cannot foster religious faith. But it is simply innumerate to declare that “we don’t know the ‘right’ demographic outcome.” The right outcome is one that keeps us within the bounds of solvency.

That is why I support an Australian-style policy that encourages immigration of high-skilled foreigners who contribute more to America’s economy than they cost. I wrote earlier this year at The American Mind: “The immigration policy outlined above is not the best solution to America’s economic problems, nor indeed is it a solution in the long term. The optimal solution is to reverse America’s cultural decline of the past two generations, but that is beyond the competence of public policy.”

Twitter

Twitter

Facebook

Facebook