Two Kinds of Détente

This essay was originally published on July 18 in Law & Liberty.

Historian Niall Ferguson, the official biographer and occasional alter ego of Henry Kissinger, proposed to “dust off that dirty word détente and engage China” in a June 5 essay for Bloomberg News. Wrote Ferguson:

Back in the 1970s, that little French duosyllable was almost synonymous with “Kissinger.” Despite turning 99 last month, the former secretary of state has not lost his ability to infuriate people on both the right and the left—witness the reaction to his suggestion at the World Economic Forum that “the dividing line [between Russia and Ukraine] should return to the status quo ante” because “pursuing the war beyond that point could turn it into a war not about the freedom of Ukraine … but into a war against Russia itself.”

Ferguson distinguished himself earlier this year as a skeptic of Western policy towards Ukraine, writing for example on March 9:

Western media seem over-eager to cover news of Russian reverses, and insufficiently attentive to the harsh fact that the invaders continue to advance on more than one front. Nor is there sufficient recognition that the Russian generals quickly realized their Plan A had failed, switching to a Plan B of massive bombardment of key cities, a playbook familiar from earlier Russian wars in Chechnya and Syria.

Prof. Ferguson’s skepticism was prescient. Far from halving Russia’s economy, US-led sanctions will cut Russia’s GDP by just 8% in the International Monetary Fund’s estimate, not nearly enough to cripple Russia’s war effort. According to a Finnish study, Russia’s energy export revenues reached a record €93 billion during the first 100 days of the war.

Russia has taken Mariupol and Severodonetsk, using massive artillery barrages that Ukraine cannot match. Russia is pursuing a war of attrition that has severely depleted both Ukraine’s manpower and ammunition stocks. Russia appears to be able to clear the sky of Ukrainian drones, possibly neutralizing the impact of American long-range rocket launchers. The outcome of the war is far from certain; at this writing, Russia appears to have the strategic initiative.

Kissinger’s controversial advice—to accept a negotiated solution with Putin’s Russia—is bitter medicine for the Biden Administration, after the president’s declaration that Putin is a war criminal who cannot be allowed to remain in office. But the facts on the ground favor Putin. Ukraine is not well-positioned to fight a war of attrition against an aggressor with four times its population. Ukraine’s stocks of ammunition, moreover, appear to be close to exhaustion, and the West does not have the means to replenish them. According to a British military think tank, a year’s worth of US production of artillery shells at the current levels would last Ukraine ten days’ worth of combat.

Whether (as Prof. John Mearsheimer and Pope Francis have suggested) the West provoked Russia’s invasion by maneuvering towards NATO membership for Ukraine is an important question, but moot under present circumstances. However wicked we believe Putin to be, we may not be able to dislodge Russia from Ukraine by any means that would not risk a nuclear war, and therefore will have to negotiate and in some way accommodate Russian strategic interests. That would be humiliating for the West in general and the Biden Administration in particular, and Prof. Ferguson deserves credit for the cold-bloodedness with which he called attention to this option.

In his June 5 essay, Ferguson warns of the dire consequences of a rush to confrontation with China. He cites Elbridge Colby’s book Strategy of Denial, which suggest ways by which the United States might interdict a hypothetical mainland Chinese invasion of Taiwan (which Colby thinks likely), and warns:

Yet it is far from clear, as retired Taiwanese Admiral Lee Hsi-Min has argued, that Taiwan would be capable of putting up as tenacious a fight as Ukraine has against Russia in the event of an invasion by the People’s Liberation Army. Moreover, in all recent Pentagon war games on Taiwan, the US team consistently loses to the Chinese team. To quote Graham Allison and Jonah Glick-Unterman, my colleagues at Harvard’s Belfer Center, “If in the near future there is a ‘limited war’ over Taiwan or along China’s periphery, the US would likely lose—or have to choose between losing and stepping up the escalation ladder to a wider war.”

Colby’s volume, “popular among the China hawks,” as Ferguson notes, has not a word to say about China’s overwhelming superiority in surface-to-ship missiles as well as long-range ballistic missiles. I pointed out this egregious omission in my January review, and have asked Colby via Twitter and other media to respond. Answer came there none. In the meantime, Prof. Oriana Skylar Mastro, an Air Force strategist, warned in the New York Times on May 28:

China’s missile force is also thought to be capable of targeting ships at sea to neutralize the main U.S. tool of power projection, aircraft carriers. The United States has the most advanced fighter jets in the world but access to just two U.S. air bases within unrefueled combat radius of the Taiwan Strait, both in Japan, compared with China’s 39 air bases within 500 miles of Taipei.

Pentagon strategists have known this for years. The late Andrew Marshall, the long-time director of the Office of Net Assessment (for whom I consulted in the early 2010s) told me that Chinese missiles unquestionably can sink US carriers by swamping existing missile defenses. That was before the Chinese developed hypersonic glide vehicles against which there presently is no defense.

In the case of Russia and Ukraine, a simple count of manpower, artillery pieces, and ammunition stocks would have led to the obvious conclusion that Russia is not easy to defeat in its “near abroad.” A count of Chinese assets, including 1,300 medium- and long-range missiles, sixty submarines, and a thousand interceptor aircraft would lead to the obvious conclusion that “it’s far from certain that the United States could hold off China,” as Prof. Mastro wrote.

The sad fact is that after thirty years of military malpractice, the United States has an army designed to attack ragtag irregulars rather than fight a modern enemy. We wrote off Russia and ignored the awakening of the Chinese giant. We were intoxicated with our victory in the Cold War and convinced that the world was ready to adopt America’s political model.

We rely on weapons systems like aircraft carriers that are vulnerable to massed missile barrages which can overwhelm our very limited missile defense capacities. The trouble is that every flag officer now serving was promoted for doing the wrong sort of thing, and the entire complex of defense think tanks, journals, specialized schools, and consultant firms were funded to do the wrong things. Elbridge Colby’s fantasy of a “strategy of denial” that ignores China’s ability to destroy whatever assets the US can field in the Western Pacific reflects the sociology of the broader defense community. To admit that the US cannot prevail over China is to confess to comprehensive incompetence over a generation of strategic planning. The defense establishment would rather spin fantasies about an easy victory over Russia or a “denial’ of Taiwan to China than admit its systemic pattern of mistakes.

In that respect, Prof. Ferguson is right. We need to dust off the dirty word “détente” because we are debilitated and lack the means to impose our will by force on Russia and China. But that is only half the story.

We need inspirational leadership to persuade American taxpayers to fund investment on this scale, like John F. Kennedy in 1962 when he told the nation that we would go to the moon, or Ronald Reagan in 1984 when he proposed to protect America against missile attack.

Ferguson is both very right and terribly wrong. Weakness forced a strategic accommodation with the Soviet Union upon the United States during the 1970s, but under the cover of détente, the United States invented the digital economy and a new generation of weapons that turned the tide in the Cold War. That had nothing to do with Kissinger, who believed that the Cold War should be managed but not won. His ascendancy began with his 1957 attack on the US strategic doctrine of massive retaliation and his advocacy of limited nuclear war, a chimerical concept embraced by a large part of the US foreign policy establishment. Thomas Schwartz reviews the record in his 2020 volume Henry Kissinger and American Power (see also my notice in Claremont Review of Books).

Russia’s massive preponderance of conventional power in the European theater, including its superiority in surface-to-air missiles, made Kissinger the man of the hour. The whole array of foreign-policy initiatives that Kissinger advanced, including arms control, failed miserably, but that wasn’t why Nixon put him in the job. America needed to buy time.

Former Deputy Secretary of Defense Bob Work explained the circumstances in a 2016 speech:

Then in 1973, the Yom Kippur War provided dramatic evidence of advances in surface-to-air missiles, and Israel’s most advanced fighters, flown by the top pilots in the Middle East, if not among the world’s best, lost their superiority for at least three days due to a SAM belt. And Israeli armored forces were savaged by ATGMs, antitank guided munitions.

U.S. analysts cranked their little models and extrapolated that the balloon went up in Europe’s central front and we had suffered attrition rates comparable to the Israelis. U.S. tactical air power would be destroyed within 17 days, and NATO would literally run out of tanks.

…. Defense Secretary Harold Brown and his Undersecretary of Defense for Research and Engineering Bill Perry, set about devising a new offset strategy. Now the first thing was just to give all our tactical systems a competitive edge by embedding modern digital electronics.

… But the real advance occurred when they said, look, let’s take all of these technologies and apply them at the operational level of war — the campaign level, combining airborne, high-resolution synthetic aperture radar, and moving target indicator radars, facilities that could fuse all this information, and both airborne and ground-launched missiles carrying new, guided munitions, to strike at the second and third echelons before they reach the forward line of troops.

In less than two years, Soviet Marshall Ogarkov famously said that reconnaissance strike complexes, the Soviet and Russian term for battle networks, could achieve the same destructive effects as low-yield tactical nuclear weapons.

As one strategist said, the Soviets now, quote, “Believe that their American rivals were scientific magicians. What they said they could do, they could do,” unquote.

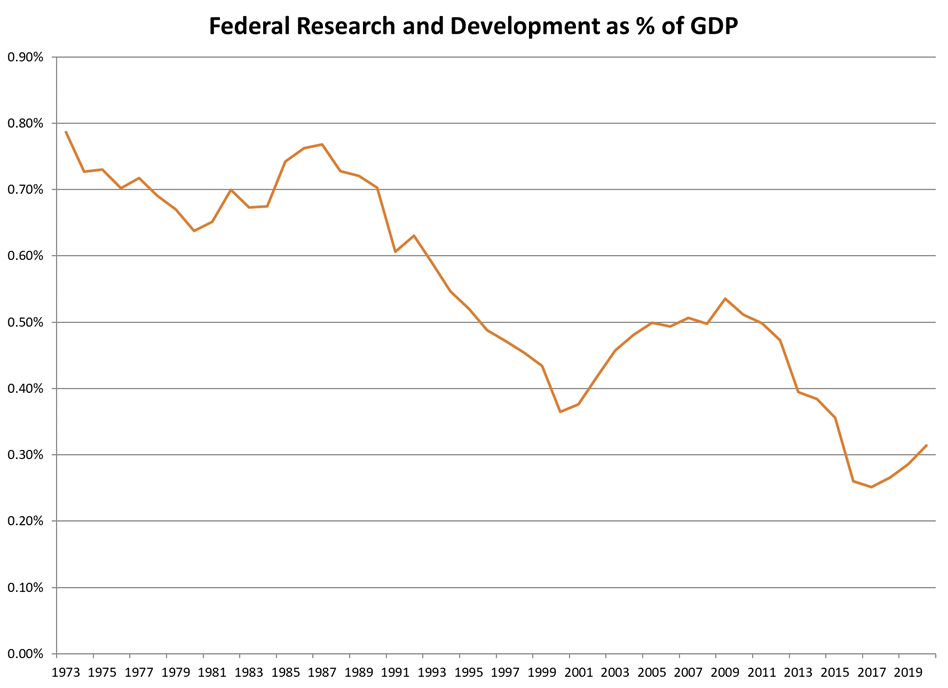

While Kissinger busied himself with arms control negotiations that ultimately proved counterproductive, Russia demonstrated the capability to destroy American planes and tanks in huge numbers. America responded with a massive commitment to defense R&D. A proxy for this commitment is the size of the federal development budget (building and testing of prototypes) as a percentage of GDP, as reported by the National Science Foundation. This remained at around 0.8% of GDP during the Carter and Reagan years, compared to just 0.3% of GDP today.

In 1976, for example, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency commissioned RCA labs to build fast and energy-efficient microchips, initially to enable weather forecasting in the cockpit of US fighter aircraft. By 1978, the CMOS chip manufacturing process made possible lockdown radar, which requires advanced computation to distinguish images below an aircraft from the background.

In the nine years between the 1973 Arab-Israeli war and the 1982 Israeli-Syrian air battle over the Beqaa valley, the United States reestablished domination of the skies. Israel used a combination of lookdown radar, AWAC-based command and control, and suicide drones to destroy nearly 100 modern Soviet-built aircraft and 17 out of the 19 Syrian surface-to-air missile batteries, with the loss of just one Israeli fighter. The Beqaa valley engagement marked the beginning of the end of the Cold War, and the end of Soviet technological superiority in key military technologies.

Henry Kissinger’s arms-control flummery and musings on limited nuclear war did not motivate America’s pursuit of détente. We had no choice after 1973, because Russia had the upper hand. But we did not leave it at that. We mobilized our technical and scientific resources on an enormous scale and created the digital revolution. That gave us war-winning technologies in conventional arms and opened the promise of an effective missile defense shield under Reagan’s Strategic Defense Initiative. It was a bipartisan commitment. Jimmy Carter’s Defense Department under the leadership of a prominent physicist, Dr. Harold Brown, developed most of the weapons systems that made America so formidable during the Reagan years.

A détente with Russia and China that accepts China’s dominance in global high-technology manufacturing and its corresponding rise as a dominant military power would be a surrender in slow-motion. It would mean the end of America’s aspirations, and a British-style decline into strategic irrelevance. But a détente that takes grim inventory of our own failings and buys us time to rebuild our technological edge is another matter. The idea will not be popular among American politicians who find it easier to denounce Vladimir Putin and Xi Jinping than to remedy our weakness at home. But it is the only path between two unacceptable alternatives: A confrontation with Russia and/or China that we might lose, and which might escalate into nuclear war, or descent into national mediocrity.

The scale of the problem is daunting. To return federal R&D funding to the levels of the late 1970s or 1980s relative to GDP, we would have to spend another $200 billion a year. The great corporate laboratories, starting with Bell Labs, no longer exist; they would have to be reconstituted. Only 7% of our college students major in engineering, against 33% in both Russia and China; Russia alone graduates as many engineers each year as the United States. These are labors of Hercules. But we have the choice of accomplishing them or condemning future generations of Americans to mediocrity. We need inspirational leadership to persuade American taxpayers to fund investment on this scale, like John F. Kennedy in 1962 when he told the nation that we would go to the moon, or Ronald Reagan in 1984 when he proposed to protect America against missile attack.

Twitter

Twitter

Facebook

Facebook