U.S. Fiscal Profligacy and the Impending Crisis

Massive demand-side stimulus combined with constraints on the supply-side in the form of higher taxes is a sure recipe for inflation and eventual recession. The Fiscal Year 2021 US budget deficit will amount to 15% of US GDP after the passage of an additional $1.9 trillion in demand stimulus, according to the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, a proportion that the United States has not seen since World War II.

It is hard to avoid the conclusion that the Biden Administration’s fiscal irresponsibility arises from a cynical political calculation. It evidently proposes to employ the federal budget as a slush fund to distribute benefits to various political constituencies, gambling that the avalanche of new debt will not cause a financial crisis before the 2022 Congressional elections. The additional $2.3 trillion in so-called infrastructure spending that the Administration has proposed consists mainly of handouts to Democratic constituencies.

Where is Foreign Money Going?

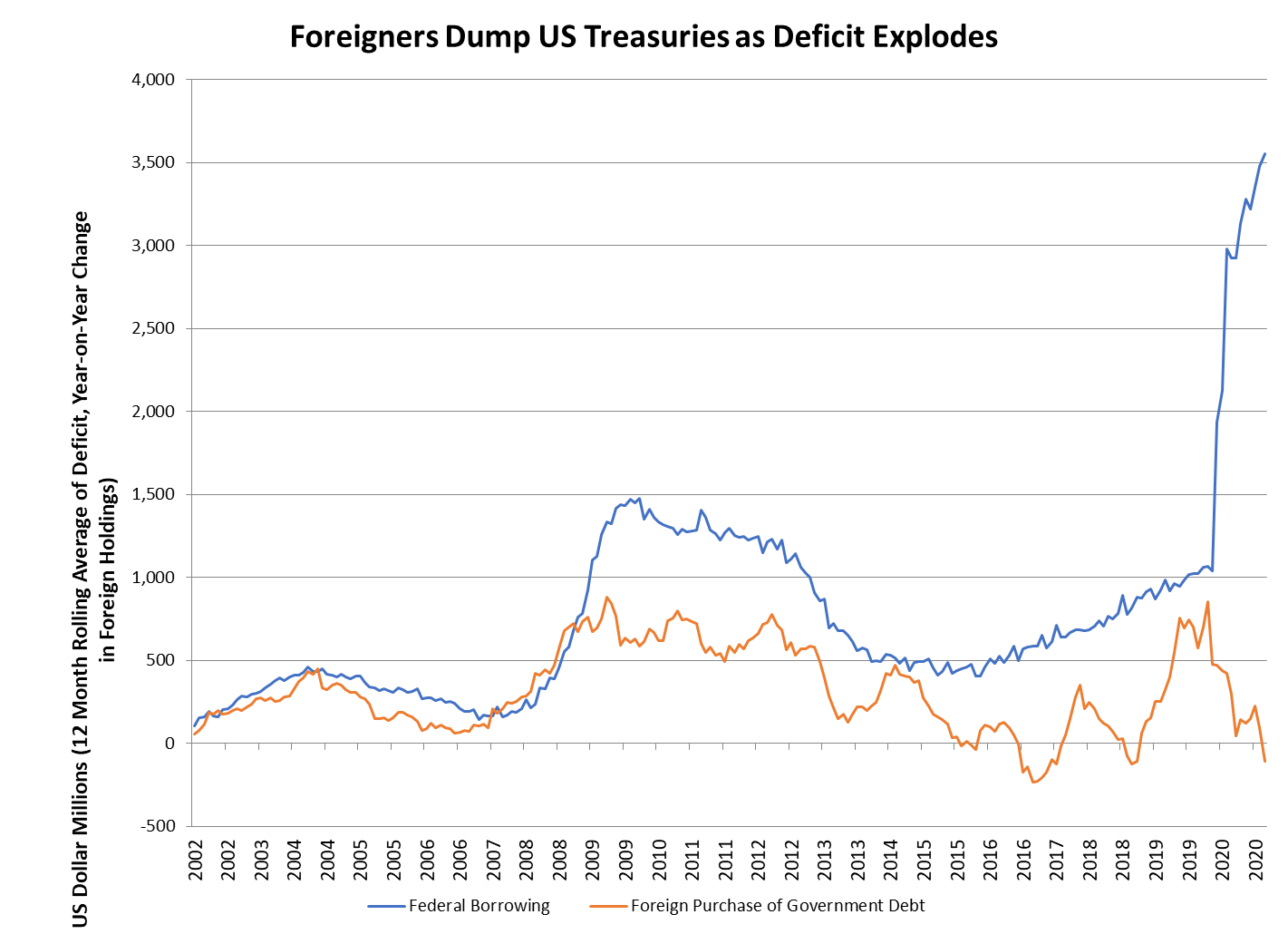

During the 12 months ending in March, the deficit stood at 19% of GDP. Even worse, the Federal Reserve absorbed virtually all the increase in outstanding debt on its balance sheet. In the aftermath of the 2009 recession, when the deficit briefly rose to 10% of GDP, foreigners bought about half the total new issuance of Treasury debt. During the past 12 months, foreigners have been net sellers of US government debt. (See Figure 1.) The US dollar’s role as the world’s principal reserve currency is eroding fast, and fiscal irresponsibility of this order threatens to accelerate the dollar’s decline.

The Federal Reserve has kept short-term interest rates low by monetizing debt, but long-term Treasury yields have risen by more than a percentage point since July. Markets know that what can’t go on forever, won’t. At some point, private holders of Treasury debt will liquidate their holdings—as foreigners have begun to do—and rates will rise sharply. (See Figure 2.) For every percentage point increase in the cost of financing federal debt, the US Treasury will have to pay an additional quarter-trillion dollars in interest. The United States well may find itself in the position of Italy in 2018, but without the rich members of the European Union to bail it out.

The flood of federal spending has had a number of dangerous effects already:

- The US trade deficit in goods as of February 2021 reached an annualized rate of more than $1 trillion a year, an all-time record. China’s exports to the US over the 12 months ending in February also reached an all-time record. Federal stimulus created demand that US productive facilities could not meet, and produced a massive import boom.

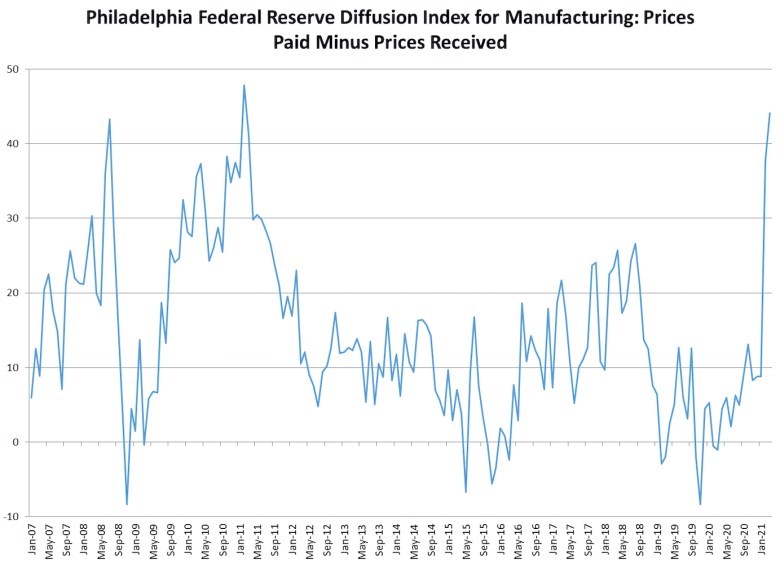

- Input prices to US manufacturers in February rose at the fastest rate since 1973, according to the Philadelphia Federal Reserve’s survey. And the gap between input prices and finished goods prices rose at the fastest rate since 2009. (See Figure 3.)

- The Producer Price Index for final demand rose at an annualized 11% rate during the first quarter. The Consumer Price Index shows year-on-year growth of only 1.7%, but that reflects dodgy measurements (for example, the price shelter, which comprises a third of the index, supposedly rose just 1.5% over the year, although home prices rose by 10%).

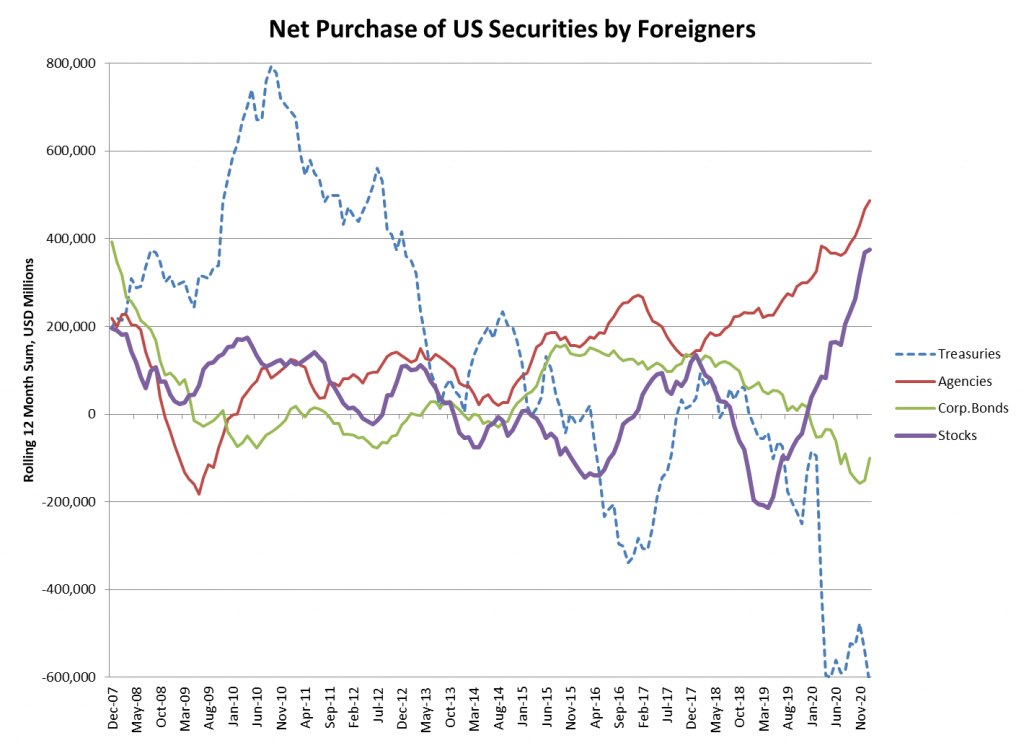

If foreigners are net sellers of US Treasury securities, how is the United States financing an external deficit in the range of $1 trillion a year? The US has two deficits to finance, the internal budget deficit, and the balance of payments deficit, and here we refer to the second. The answer is: By selling stocks to foreigners, according to Treasury data. (See Figure 4.) Foreign investors have been dumping low-yielding US Treasuries and corporate bonds during the past year, according to the Treasury International Capital (TIC) system. Foreign investors bought $400 billion of US equities and nearly $500 billion of US agency securities (backed by home mortgages) during the 12 months through January, but sold $600 billion of Treasuries and $100 billion of corporate bonds.

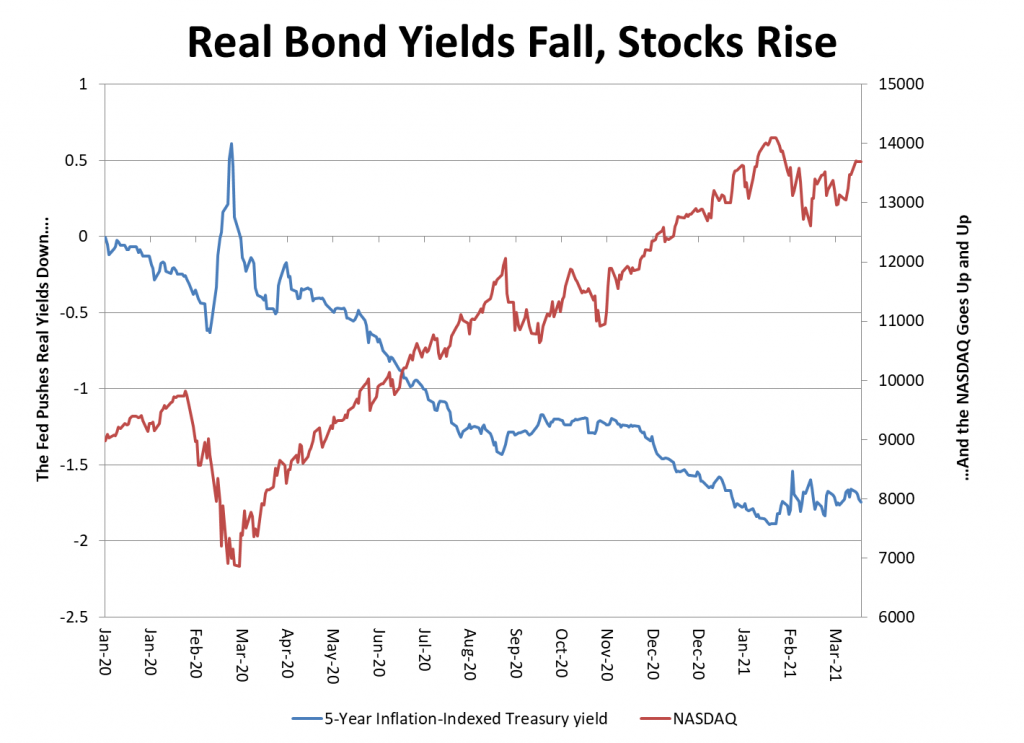

This is a bubble on top of a bubble. The Federal Reserve buys $4 trillion of Treasury securities and pushes the after-inflation yield below zero. That pushes investors into stocks. Foreigners don’t want US Treasuries at negative real yields, but they buy into stock market which keeps rising, because the Fed is pushing down bond yields, and so forth.

At some point, foreigners will have a bellyful of overpriced US stocks and will stop buying them. When this happens, the Treasury will have to sell more bonds to foreigners, but that means allowing interest rates to rise, because foreigners won’t buy US bonds at extremely low yields. Rising bond yields will push stock prices down further, which means that foreigners will sell more stocks, and the Treasury will have to sell more bonds to foreigners, and so forth.

The 2009 crisis came from the demand side. When the housing bubble collapsed, trillions of dollars of derivative securities backed by home loans collapsed with it, wiping out the equity of homeowners and the capital base of the banking system. The 2021 stagflation—the unhappy combination of rising prices and falling output—is a supply-side phenomenon. That’s what happens when governments throw trillions of dollars of money out of a helicopter, while infrastructure and plant capacity deteriorate.

The source of the 2008 crisis was overextension of leverage to homeowners and corporations. I was one of a small minority of economists who predicted that crisis.

Federal debt in 2008 was 60% of GDP, not counting the unfunded liabilities of Medicare and the Social Security System. As of the end of 2020, Federal debt had more than doubled as a percentage of GDP, to 130%. The Federal Reserve in 2008 owned only $1 trillion of securities. US government debt remained a safe harbor asset; after the Lehman Brothers bankruptcy in September 2008, the 30-year US Treasury yield fell from 4.7% to 2.64%, as private investors bought Treasuries as a refuge.

The Treasury: Not a Refuge from, but a Cause of Crisis

Today the US Treasury market is the weak link in the financial system, supported only by the central bank’s monetization of debt. If the extreme fiscal profligacy of the Biden Administration prompts private investors to exit the Treasury market, there will be no safe assets left in dollar financial markets. The knock-on effects would be extremely hard to control

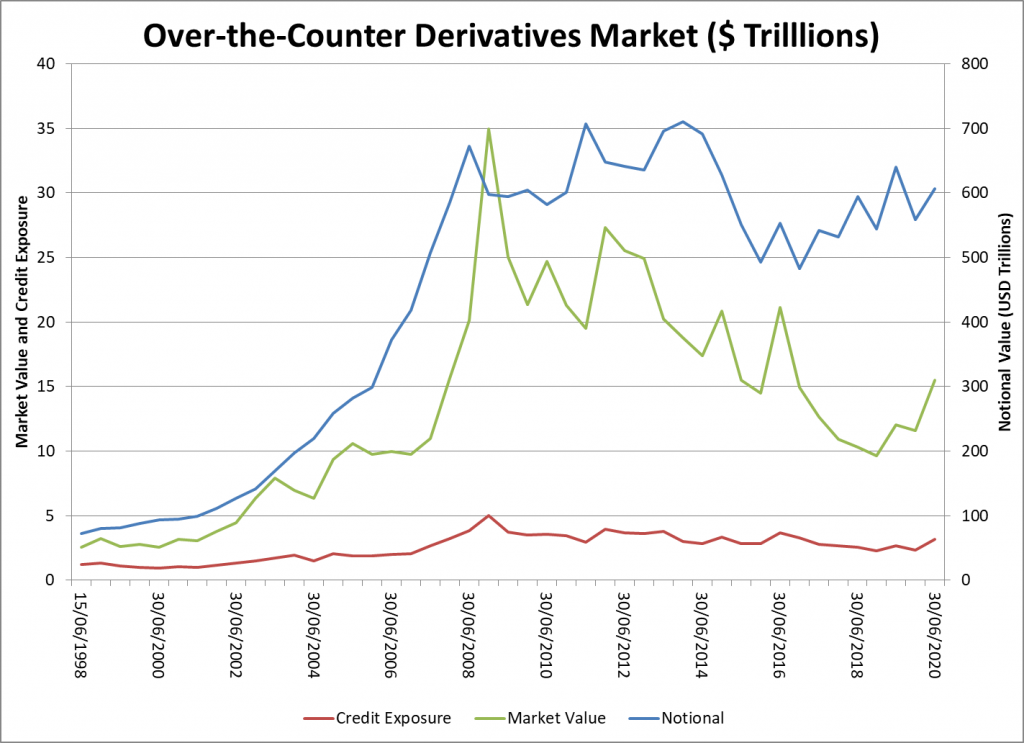

The overwhelming majority of over-the-counter (privately traded) derivatives contracts serve as interest-rate hedges. Market participants typically pledge Treasury securities as collateral for these contracts. The notional value of such contracts now exceeds $600 trillion, according to the Bank for International Settlements. Derivatives contracts entail a certain amount of market risk, and banks will enter into them with customers who want to hedge interest-rate positions only if the customers put up collateral (like the cash margin on a stock bought on credit) (See Figure 5) The market value (after netting for matching contracts that cancel each other out) is about $15 trillion. If the prices of Treasury securities fall sharply, the result will be a global margin call in the derivatives market, forcing the liquidation of vast amounts of positions.

Something like this occurred between March 6 and March 18, 2020, when the yield on inflation-protected US Treasury securities (TIPS) jumped from about negative 0.6% to positive 0.6% in two weeks. The COVID-19 crash prompted a run on cash at American banks, as US corporate borrowers drew down their credit lines. US banks in turn cut credit lines to European and Japanese banks, who were forced to withdraw funding to their customers for currency hedges on holdings of US Treasury securities. The customers in turn liquidated US Treasury securities, and the Treasury market crashed. That was the first time that a Treasury market crash coincided with a stock market crash: Instead of acting as a crisis refuge, the US Treasury market became the epicenter of the crisis.

The Federal Reserve quickly stabilized the market through massive purchases of Treasury securities, and through the extension of dollar swap lines to European central banks, which in return restored dollar liquidity to their customers. These emergency actions were justified by the extraordinary circumstances of March 2020: An external shock, namely the COVID-19 pandemic, upended financial markets, and the central bank acted responsibility in extending liquidity to the market. But the Federal Reserve and the Biden Administration now propose to extend these emergency measures into a continuing flood of demand. The consequences will be dire.

The present situation is unprecedented in another way: Not in the past century has the United States faced a competitor with an economy as big as ours, growing much faster than ours, with ambitions to displace us as the world’s leading power. China believes that America’s fiscal irresponsibility will undermine the dollar’s status as world reserve currency.

Here is what Fudan University Professor Bai Gang told the Observer, a news site close to China’s State Council:

Simply put, this year the United States has issued a massive amount of currency, which has given the US economy, which has been severely or partially shut down due to the COVID-19 epidemic, a certain kind of survival power. On the one hand, it must be recognized that this method . . . is highly effective. . . . The US stock market once again hit a record high.

But what I want to emphasize is that this approach comes at the cost of the future effectiveness of the dollar lending system. You do not get the benefit without having to bear its necessary costs.

A hegemonic country can maintain its currency hegemony for a period of time even after the national hegemony has been lost. After Britain lost its global hegemony, at least in the 1920s and 1930s, the pound sterling still maintained the function of the world’s most important currency payment method. To a certain extent, the hegemony of the US dollar is stronger than any currency before it. . . .

We see that the US dollar, as the most important national currency in the international payment system, may still persist for a long time even after US hegemony ends. Since this year, the US has continued to issue more currency to ease the internal situation. The pressure will eventually seriously damage the status of the US dollar as the core currency in the international payment system.

America has enormous power, but the Biden Administration and the Federal Reserve are abusing it. And China is waiting for the next crisis to assert its primacy in the world economy.

This essay was originally published by Law & Liberty as part of a symposium on Debt, Inflation, and the Future.

Twitter

Twitter

Facebook

Facebook